"Give Thanks" Bonus Content

For years, I have struggled with the holiday we call Thanksgiving. For Native people, gratitude is defined differently than the false narrative taught to us as children

Myths are a means by which people explain their world and their beliefs. Myths promote a certain perspective of a culture. Myths are not the same as truths.

The Thanksgiving story, taught to American children for generations, is not the truth. In fact, it is a harmful lie that perpetuates a narrative about colonization that should not be tolerated. It romanticizes the displacement of the sovereign indigenous nations that existed on this land of ours for centuries before Europeans came and laid claim to it, stole it, called it theirs and began to create stories. It embraces the myths that erase the truth of colonization, genocide and centuries of egregious policies intended to eradicate a race of people indigenous to North America.

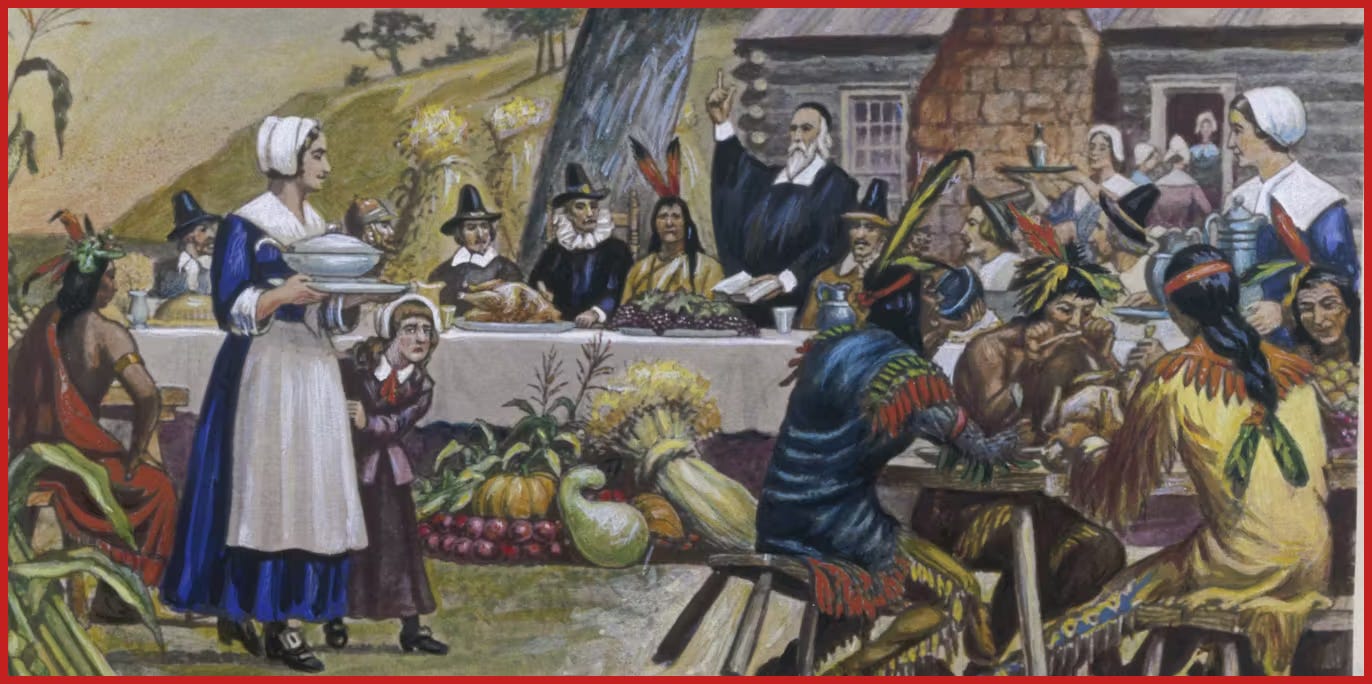

The Thanksgiving story taught to our children about the well-meaning Pilgrims and the generous Indians—the beautiful images of shared bounty and shared gratitude—omits the truth.

“The antidote to feel-good history is not feel-bad history but honest and inclusive history”

James W. Loewen, “Plagues and Pilgrims: The Truth About the First Thanksgiving”

By 1620, when the Pilgrims set foot on Plymouth Rock and figuratively on the necks of Native people, the Wampanoag population had been devastated by diseases introduced by earlier Europeans—traders and trappers. Villages were wiped out. Some estimates put their decimation by disease at 90%.

The many sovereign Native nations that existed at the time were sophisticated, successful and longstanding. As with other nations, these nations forged alliances and had political adversaries. The Narragansett were far less impacted by European diseases and outnumbered the Wampanoag greatly. Conflict loomed. The Wampanoag pragmatically sought an alliance with the interlopers from the Mayflower. Civilizations are complex.

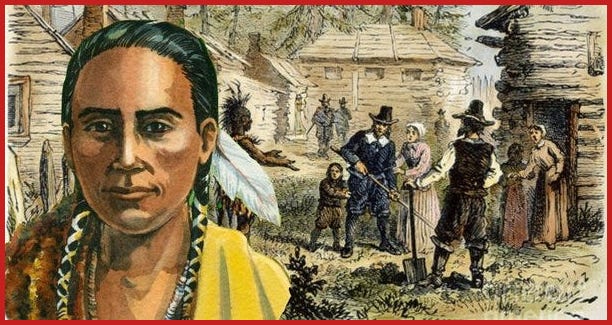

With the aid of an English-speaking Pawtuxet Indian named Tisquantum (not Squanto), the Wampanoag arranged an exchange of European weaponry for food, and for a brief time, a friendly association existed. By the way, Tisquantum had earlier been kidnapped and taken to Europe, where he learned English before he escaping slavery and returning to his native land.

There’s more to the story of the Wampanoag. It includes cruel slaughter, massacre and decimation. It’s a story that elevates the Pilgrims and other European interlopers to the top of a White pecking order that exists to this day. Sadly, progress we have made to begin a reconciliation process including truth-telling is being stopped by the current shameful administration.

As a child, I learned the story of the first Thanksgiving with all my classmates. I traced the outline of my small hand on construction paper and turned it into an image of a turkey. I was proud to see it displayed on the front of our refrigerator. I celebrated the holiday alongside my father and mother and relatives. It was a fine day to gather with family. I don’t remember looking at Daddy and wondering about our ancestors—not when I was little, not when I’d learned the pretty lie about our nation’s history at school. But as I grew older, I questioned why. Why are we celebrating this day?

Tradition is baked into us. Breaking tradition is not easy. For those of us who are mixed-race, it puts us in the uncomfortable position of feeling like we’re picking a side. And besides, it’s just a day. A national day of thanksgiving. Thankfulness for the bounty we enjoy as Americans. What kind of ungrateful shitass would I be to refuse to celebrate such a day?

It took me decades to reconcile it—the conflicted emotions. But when I did, it was a straightforward decision. I will not participate in a lie, a harmful falsehood that perpetuates stereotypes and hides the truth of how our country was built. It was a straightforward decision, but it isn’t without a difficult outcome. Again, I straddled a chasm between cultures. I am not ashamed of either side of my family. Certainly, my White mother did not massacre a single Indian. She married one, and together they created a child. Together, they lived the best examples of goodness I could ever have.

What I regret about not celebrating the national day of thanksgiving is the meal my mother was such a master at creating. Cooking was not a passion for her. It was mostly a chore—it didn’t come easily. Daddy used to say, “It takes your mother two hours to get nervous enough to start cooking.” But Thanksgiving is the day she really shined. No one could make a turkey as juicy and flavorful or gravy as rich and delicious. And the standout was her cornbread dressing. Best I ever had. Thanksgiving was the one meal I stood by and watched her make. It was perfect. I miss it. We miss it. So, on this Mothers’ Day, we are going to have turkey and dressing—all the things we grew up enjoying and anticipating all year. It will be a perfect and meaningful way to remember and honor our family’s tradition of a very particular meal we all loved so much.

I am thankful every day for my father and mother. Thankful for my life in this country. Thankful when I see us as a country moving toward truth and reconciliation for the sins of the past. But I’m sad and despairing when I see us being dragged backward toward deceit and bigotry.

I hope you enjoyed my story Give Thanks. I hope it provoked thought about the myths we cling to and the need to abandon myths that do not promote understanding, love and truth.

This is a beautiful description of the mixed feelings you have gone through, Lucinda. Years ago the plight of Native Americans was not even considered. Pretty amazing, no? Was the Alcatraz occupation with Oakes the beginnings of awareness? Paul remembers it quite well as a guy from his work was Native American, Chief Eagle, who went over for a day, kept him up on it. I was in SoCal, fresh from the midwest, so pretty far removed. Still there is so little given to the Native Americans. It's shameful. The same can be said for Blacks, too. Is it bc of social embarrassment of having treated so many so horribly? These lines really resonated for me, Lucinda: "Tradition is baked into us. Breaking tradition is not easy. For those of us who are mixed-race, it puts us in the uncomfortable position of feeling like we’re picking a side." How conflicted you must have felt. It's good you are writing your way out of it (I think you are).

Thanks for this very personal and very insightful look at Thanksgiving, which gives me tremendous pause as it had been one of my most favorite holidays, primarily for the food. The idea of transferring the menu to another special day is one I will definitely consider. Again thanks for the courage and the immense creativity you are giving to us.