In my story Who’s Your Daddy?, I included parts of the story my father told me about crossing the North Atlantic on the Queen Mary in 1942.

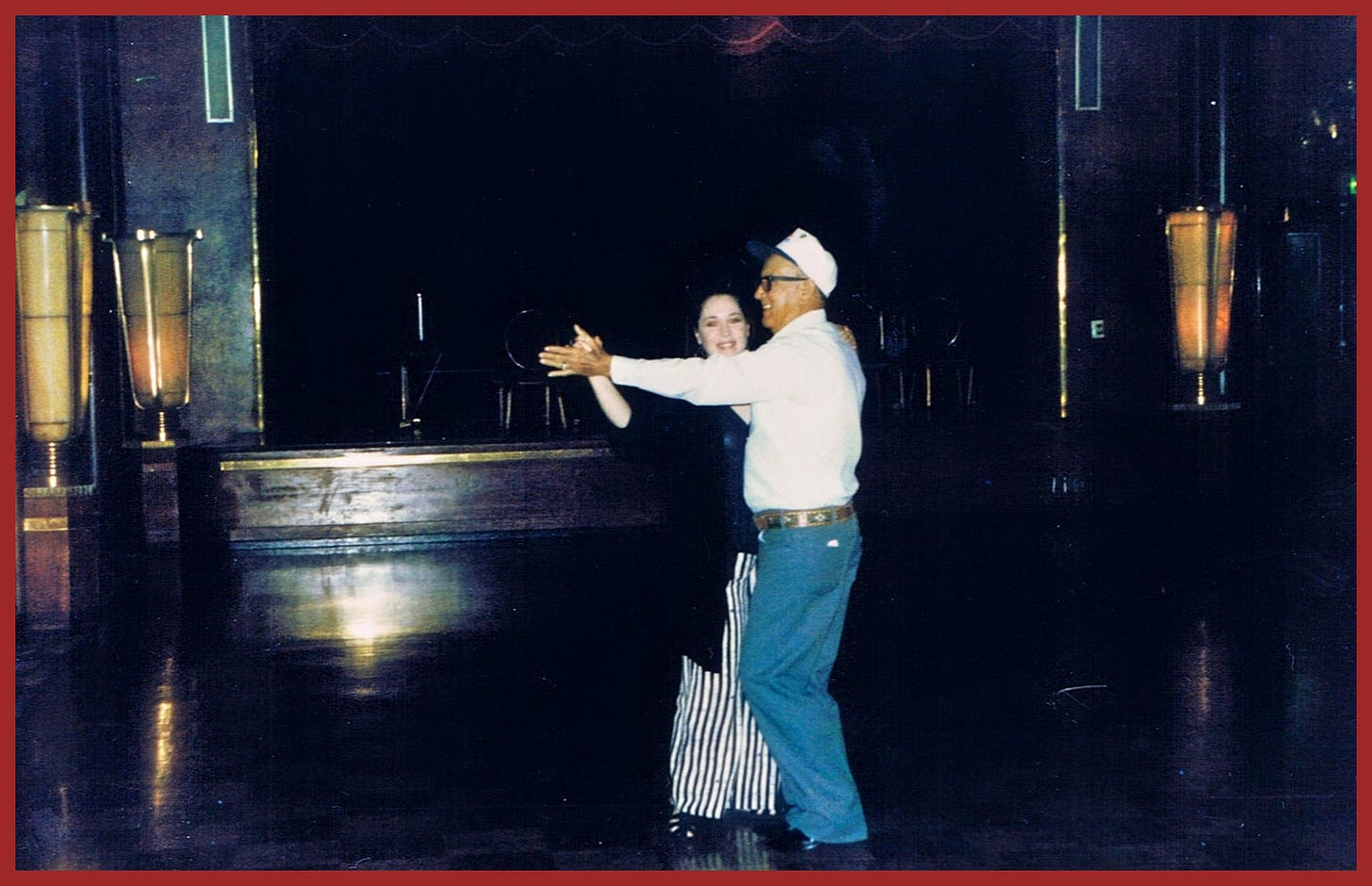

Years later, Daddy and I visited the Queen Mary when he was here in L.A. for a visit. Daddy’s memory was as detailed and complete as any encyclopedia, full of personal anecdotes and historical facts that he transformed into practical knowledge that especially appealed to me. Daddy’s memories are my memories—they are the most valuable inheritance I received from him. As we walked together on The Mary, Daddy and I became the same person.

The Queen Mary was destined to be a great and historic ship. Spacious staterooms, ballrooms, a swimming pool and lavish dining rooms made the enormous liner the foremost indulgence for transcontinental travel by celebrities and heads of state.

When she was requisitioned to be a troop transport ship during WWII, all the trappings of luxury were stripped and stored so her enormous size could hold the tens of thousands of soldiers en route to fight tyranny on foreign soil. The Mary became The Grey Ghost. She carried 810,000 military personnel during WWII. As the Queen Mary, the liner made the ocean crossing in an astounding five days. The Grey Ghost took as long as two weeks, zigzagging and finessing her way across the treacherous Atlantic made more dangerous by German Wolf Packs stalking her. Hitler placed a bounty on the Queen Mary and promised any U-Boat captain who sank her 1,000,000 Reichsmarks, as well as Oak Leaves to the Knight’s Cross, Germany’s highest military honor.

Daddy made his crossing when the weather was warm, allowing for more men to be transported because men could sleep on deck as well as below. We stood together on the deck, and he pointed out the spot where he slept and spent most of the days making his way to the unknown. Daddy said, “I lived on vanilla wafers, black coffee and cigarettes all the way across the Atlantic.”

Our tour included details about the amount of food on the Grey Ghost’s crossing: 20 tons of meat, 5 tons of ham and bacon, 2,000 quarts of ice cream, 280 barrels of flour, 50,000 pounds of potatoes, 60,000 eggs, 12,800 pounds of sugar and 1,200 pounds of coffee. So, I was surprised when Daddy said he ate only vanilla wafers. “I went down to the mess hall the first night,” he said. “They were carving what they said was roast beeves, but, Nubbin, I knew better. Beeves are not that big…” He paused. “I knew it was horsemeat they were feeding us, and I never went back.” The army did, in fact, use horsemeat during WWII. It was controversial, but there was a meat shortage.

Daddy also described how the men slept, stacked “like cordwood.” Up on deck, in lieu of a cot, a man sat between another’s open legs, leaned back on his chest, then another, then another. American GIs provided each other a place to lean, sleep, lie awake, smoke cigarettes and wonder what they were sailing toward.

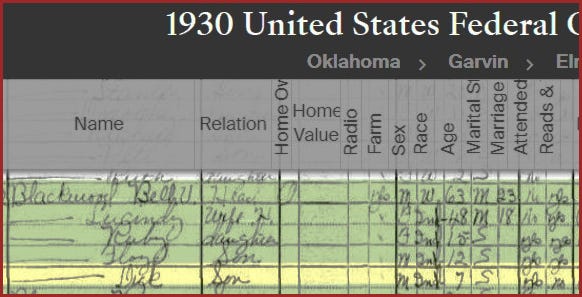

As a young GI, Daddy knew very little about his ancestral background beyond Oklahoma. He knew this: He was a Choctaw/Caddo Indian from Oklahoma. His father was white and had come to Oklahoma, married an Indian woman—Lucinda—and they had three children. And he died when Daddy was only eight years old.

Who was my daddy’s daddy? My grandfather was B. V. Blackwood. Daddy called him Papa. Daddy’s memories of him were precious few. He remembered how his Papa plowed the land, the horse or mule that pulled his plow. He remembered his father’s white sons from his first marriage. He remembered his uproarious Blackwood uncles—B.V.’s brothers—playing music, buying bootleg whiskey, raising hell on Saturday nights. The Blackwoods were a fun bunch. B. V. was a Mason, 32nd degree Scottish Rite. He practiced the ancient tenets of freemasonry. Daddy could remember sneaking down to the barn, eavesdropping on his father as he tutored men, imparted the secret text and teachings of the Masonic Lodge to others. I won’t defend or argue Yay or Nay the merits or evils of freemasonry. For my father, it was one of the few precious memories he had of his Papa.

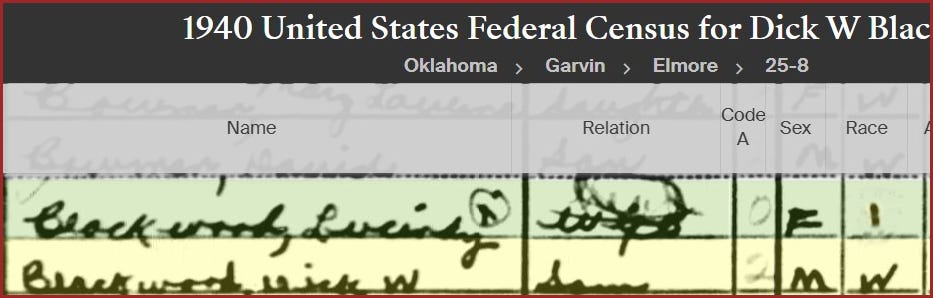

Daddy grew up an Indian. When Daddy was little, the U.S. Census records show just one “W” for the Blackwood home: B.V. Blackwood, head of household. All the rest, my grandmother, grandfather, great grandmother, aunts, uncles and my father were listed as “I”—all Indians. On the next census, after Daddy survived Indian Boarding School, he was listed as a “W,” too. That’s one example of Assimilation = Genocide.

But Daddy knew very little about “W,” the White part, his Papa’s part.

When the Grey Ghost finally reached Scotland, Daddy was among the thousands of GIs met by a pipe-and-drum band. They were welcomed joyously by sidewalks full of cheering Scots, paraded through the cobblestone streets of this foreign land.

What my father didn’t know at the time was that the name Blackwood, given to him by his white father, was Scottish. He didn’t know his white roots were in Scotland. He didn’t know Blackwood was a city in Scotland.

Daddy certainly didn’t know that one of our ancestors, Adam Blackwood, was a renowned scholar, lawyer and author who lived in exile in France because of his dangerous loyalty to Mary, Queen of Scots. He didn’t know Mary was Adam Blackwood’s patron and that he was the prolific writer of pamphlets supporting her against Tudor Queen Elizabeth I. Daddy didn’t know about the plaque dedicated to Adam Blackwood in the church in Poitiers, France.

Ultimately, what Daddy didn’t know was that when he disembarked from the Grey Ghost and set foot on Scottish soil, the young Native American GI was also coming home. The Scottish pipes and drums that celebrated him and those thousands of soldiers with “Scotland the Brave” and other traditional tunes were part of his Blackwood heritage.

Daddy was many things. He was a devoted father, a proud lifelong Democrat, a Masonic leader, a valued employee of Mobil Oil Company, a proud Native American, a member of the Choctaw Tribe of Oklahoma. And he was Scots, too.

It was to the strains of “Scotland the Brave” that my father’s casket was carried to his final resting place on The Good Earth.

I am fortunate to know Who Is My Daddy. I’m fortunate to have been close, had many years together. A day does not pass that I don’t think of him—sometimes we are the same person.

I loved this Lucinda. It's so great you and your dad went to the Queen Mary and he could tell you so many stories of what it was like. I was amazed at the photo - of SO many packed onto the decks of the ship. I was on the Queen Mary in Long Beach probably in the mid 80s and she had reclaimed her glamour. Simply amazing at the amount of people she transferred. A great post. Love the history, and your family history!!!

Thank you for sharing your relationship and history your dad, with us avid readers. My Dad shared a few of his stories of WW2 aftermath and clean up with me. He was pretty tight lipped about most of it. He too talked about the ships. He was the Colonel’s mechanic for his unit and sometimes jeep driver. This makes me want to look more closely at my mother’s heritage in the Choctaw nation.