Simpson’s scissors were snipping at a familiar head of hair while the barber observed his customer reflected in the mirror. Red Griffin, a carpenter, sat in the only chair in the shop he would occupy. It was furthest from the door and provided some distance from any gusts of wind that might accompany other customers as they came and went.

The bell over the door announced every coming and going with a cheerful tinkle that irritated Red. Red Griffin, when he cussed—and he cussed almost as often as he breathed air—moved his head from side to side emphasizing each cuss word and making it hard for the scissors to keep up. “Goddamit, Simpson, do we have to listen to those goddamned bells every goddamn time some SOB comes or goes?” Simpson absently nodded to Red’s mirrored image and looked to see who had just come through the door.

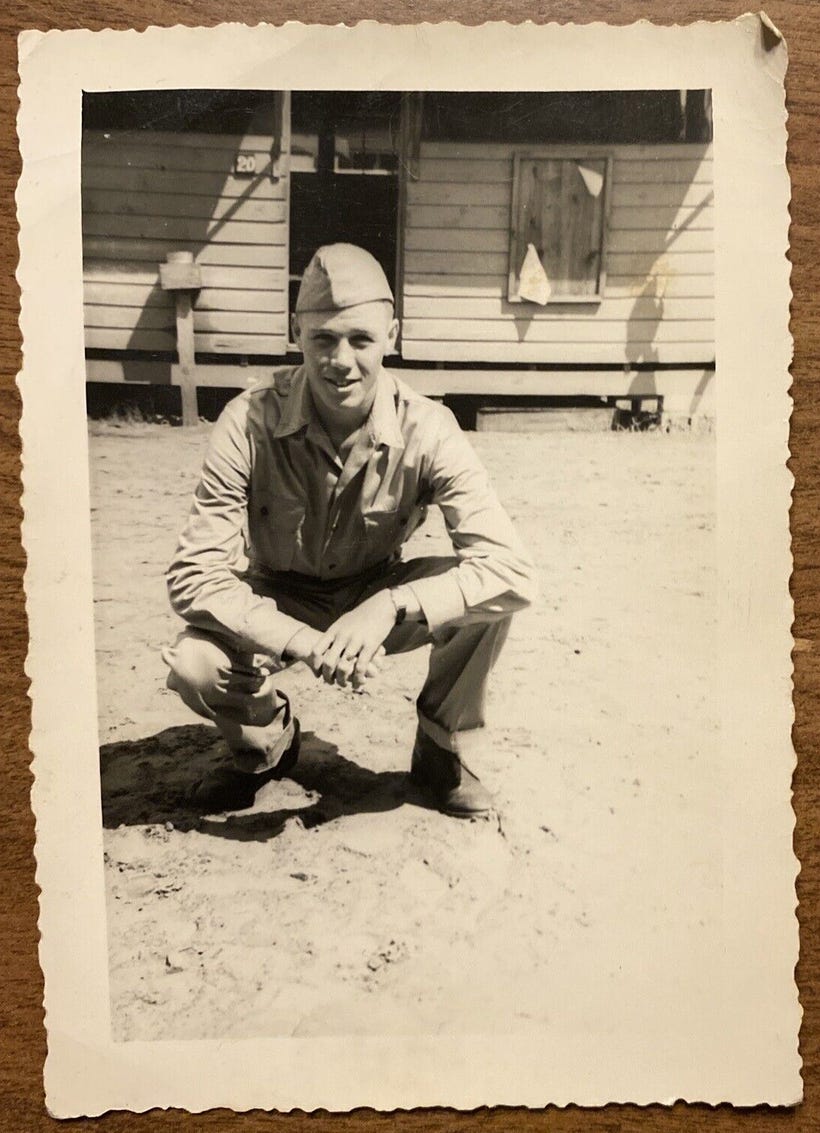

It was a young man in an army uniform. He nodded to the barber to indicate he wanted a haircut, and from the looks of him, he was going to want a shave, too. He took a seat in front of the windows that looked out to Main Street and began to leaf through a magazine. The young man looked familiar to the barber, but he couldn’t place him quite yet. The barber’s scissors over the years had taken on muscle memory. They could cut a familiar head of hair without supervision from the barber, and that afforded the barber the luxury of mentally quitting his vocation and taking up his avocation—observer of human nature and archeologist and chief excavator of Dixon and Beal County lore. He’d soon have this young man clocked.

The old carpenter drew a bead on the young man, too. Red’s incisive pale blue eyes, set in his ruddy-complected face, didn’t miss a thing. But having seen something, Red was apt to come to an immediate conclusion that no amount of reason or explanation could change.

Simpson’s Barbershop was just across the street from the courthouse square. The male population of Dixon held to the notion that the beauty shops were where town gossip was hatched and spread, but plenty of information was gathered and disseminated by the men who emerged from the barbershop with fresh haircuts, perfectly trimmed sideburns and smelling of witch hazel.

Red Griffin’s pale-eyed scrutiny began to cause the young man in the uniform to feel uneasy. He sat still and tried his best to blend into the background. Red commenced a conversation with the young man—a pretty one-sided conversation, more of an inquisition. Red’s aim was to suss out just who this man was and who he was kin to. The young man answered his questions. Characteristically, Red stuck to the conclusion he had reached even before he began the interrogation. Then he settled a question that was not really in question by saying adamantly, “I don’t give a good goddamn who you say your daddy is. I know your daddy is Abe Henry.”

This was a time and place where the use of “daddy” wasn’t considered childish. Grown men and women called their fathers Daddy until they day they died.

The young man was too tired, too world-weary, to try to dispute the word of stubborn Ol’ Red Griffin—or any of the old-timers around Dixon—even on a subject as basic as his own parentage. Reciting a rundown of family relations and histories—who was kin to who, where they’d come from, and how long they’d been in Dixon—was a common occurrence, especially among the old-timers in town. This might have been because Dixon had for many years attracted people from different places: points east, west, north and south. Simpson, the barber and archeologist, had honed his skills to a fine point, but even he wasn’t about to dispute the carpenter Red Griffin.

However, here is the rundown. John Francis Henry, Sr.—Big Frank, as he was called—was the father of John Francis Henry, Jr—Little Frank, as he was called—and Little Frank was the father of John Francis Henry III—Trey, as he was called. And Trey Henry, the beleaguered young man in uniform sitting in Simpson’s Barbershop, was not the son of Abe Henry, as Red Griffin had just proclaimed him to be.

As it happened, there were two Henry families in Dixon, and they were not related. The other Henry family, the one headed by Abe Henry, was from Oklahoma and had been in Dixon for a mere generation. He and his wife had come to Dixon after Abe found work in the oil field, while the Frank Henry family—which included Big Frank, Little Frank and Trey—had originated in West Texas and homesteaded a little place west of Dixon that had, after several generations, grown into a sizable ranch.

After his demobilization from Europe in late 1945, John Francis Henry III—Trey—and an army buddy of his had hitched a ride all the way from East Texas—which is as far as the U.S. Army took them—with a real nice fellow who not only went way out of his way but didn’t charge them a penny for the ride home—a favor that was greatly appreciated after the ordeal they’d been through to get home.

Returning millions of troops from the various theatres of war was a feat almost as challenging as the ultimate victory over the Axis powers. Operation Magic Carpet began just after VJ day, transporting more than 22,000 Americans back home every day. In the span of 360 days, some 8 million men and women from every service branch, scattered across the globe, were returned to the shores of the United States of America. It was an enormous, ultimately successful endeavor but not without controversy. In an operation of that size, it’s no wonder there were snafus.

There was near revolt at times. On the home front, there was public outcry early on that clamored for the return of troops by Christmas of 1945 with the slogan “Home Alive by ‘45.” Policy regarding the order in which troops were returned changed a number of times. GIs scrambled to put together the 85 points needed for the complicated and, what many thought, unfair system of prioritization. Later, when the required points were decreased to as low as 50, bottlenecks were created by the great number of newly qualified troops and the limited number of transport ships to accommodate them.

The demobilization effort worked from the outset. Over 3 million soldiers were returned home in just five months after VE day. Nevertheless, stateside “Bring Daddy Home” groups sprang up. Servicemen’s wives sent off pictures of their children along with hundreds of baby shoes labeled “Please bring back my daddy.”

When John Francis Henry III happily stepped foot aboard a Merchant Marine ship in France to sail home in mid-November of 1945, his relief was enormous. On November 22nd, Thanksgiving Day, as the ship sailed through the Dover Strait past miles of white chalk cliffs, many of the men put down their eating utensils and joined in a less beautiful but more moving rendition of Vera Lynn’s wartime song that promised bluebirds, love and laughter and peace ever after tomorrow when the world is free.

As young Trey Henry sat in Simpson’s Barbershop, he patted the inside pocket of his jacket and felt the printed menu of the bounteous Thanksgiving feast he’d shared with a mass of hungry, grateful GIs not so many days since but thousands of miles away and what seemed like a lifetime ago. That Thanksgiving had surely been the most grateful day of his life. And now he was home. Back home in Dixon at last.

When they pulled into Dixon, Trey asked the nice man to let him off in front of the courthouse square. Municipal crews were busy stringing up Christmas decorations, such as they were—the single strands of green and red bulbs that went up year after year. For Trey, the modest display looked like a Welcome Home sign. He took in the air, the sky, the stores and businesses, the look of the place where he'd grown up. All the familiar things he’d missed, longed for and imagined for so long. Then he ambled across the street to Simpson’s to get a fresh shave and haircut before going the rest of the way home.

As much as he was looking forward to seeing his family, he knew the reunion, joyful as it would be, would also be draining. More than anything, he wanted to curl up in a bed and sleep for a week. They had driven almost straight through, stopping only to let Bud Spencer, Trey’s traveling companion, off in Abilene in front of a small frame house with a gold star in the window. Bud’s mother had lost her oldest boy in the Pacific. As they drove away, Trey looked back and saw the woman fling open the screen door and collapse into her younger son’s arms. Trey fought back emotions for the next few miles as he and the man, just the two of them, made the last leg of the trip on into Dixon.

Trey answered all the questions the man asked about the time he’d spent in Europe, including what it had felt like to set foot on foreign soil for the first time and how it felt to be coming home. And he had one question after another about the turbulent time in between. Stories Trey didn’t want to recount so soon, but he felt obligated to, considering the free ride. As they ticked off the miles and his longed-for destination grew closer, an almost paralyzing weariness took hold of him. Just three years had passed, but after all he’d seen and done, he felt older by a lifetime.

To kill a little more time after his shave and haircut, he stopped in at Powell Drugstore and was surprised to see Jerry Dale Griffin working there. Red Griffin, the stubborn coot from the barbershop, was her daddy, a fact Trey knew for sure. He and Jerry Dale had been in school together, but she was at least three years behind him. He remembered her being practically a child when he joined the Army. He sat down on a red vinyl-covered stool, spun around on the chrome base, lit a cigarette and asked for a large chocolate milkshake. Jerry Dale looked stricken and suggested he have a Coke float instead, but that wouldn’t do. He told her he’d been craving a milkshake ever since he left Dixon, so reluctantly she started mixing it up. After many minutes and much nervous fidgeting and glancing over her shoulder at Trey, Jerry Dale inserted a straw and almost apologetically set the tall cut-glass tumbler in front of her customer. He took a strong pull on the straw, expecting thick, sweet deliciousness to slowly rise up but was surprised at how quickly the soupy chocolate filled his mouth. Not knowing that milkshake making was Jerry Dale’s Achilles heel, he wondered if his memories of the delicious stateside treat were wrong.

Jerry Dale, eager to take his attention away from the milkshake, began a lively chat. He found out what Jerry Dale had been doing while the world was at war. Come to find out, she had worked summers at the airbase close by where she was tasked with keeping files and records of fighter planes and the big B-52s and transport aircraft that were being retired. “Pickled,” they called it. Truth be told, she’d had a grand time working at the airbase because it afforded her some time to be herself and a respite from the duties of caring for the houseful of her young motherless siblings. Before long, Red Griffin came in to buy a Life magazine and offered, at Jerry Dale’s suggestion, to drive Trey home, out to the Ten Twenty Ranch, home to John Francis Henry, Jr.

Red didn’t so much as blink or acknowledge that he’d been wrong about who Trey’s daddy was. Just said, “Glad to do it, son. Welcome home.”

The next weeks were a jumble. Mixed emotions, happiness, restlessness, odd longings for distant places Trey had thought he would never care to see again. While he’d been gone, in spite of the misery of war, there had been a distinct freedom for him, too. Freedom from anything besides the present and the need to simply stay alive. In the Army, even though he was obliged to take orders without questioning, he was his own man in ways he hadn’t experienced before. On liberty at the pubs and dancehalls, drinking, dancing to American music, holding pretty foreign girls—liberated and grateful, their arms wrapped around his neck and behaving in ways that were less inhibited than the American girls he was used to—Trey and his fellow GIs enjoyed being free for a while from American social restrictions and their own inhibitions.

He hadn’t been home more than a few days and not nearly rested up when his father summoned him to get a move on and help him work cattle and do all the things it took to keep up the ranch. His mother was eager to get him back on track, too. She seemed to sense that he’d had a taste of life that wasn’t compatible with plans she had in mind for him. At night, he would lie awake, staring at the ceiling of his bedroom, look around at trophies he’d won playing football and running track and wonder who that boy was and where he had gone. He’d written home enthusing over the GI Bill and how he’d be able to access funding for college and a home loan, but since arriving home there’d been no mention of it, and he hesitated to bring it up. After all, he’d been gone a long time, and well, he thought, maybe he should just put his head down and do what was needed and expected of him. He knew what he’d always known. Education or no, like his daddy and grandfather, he’d spend his life carrying on the family’s cow business and legacy.

Despite being called Little Frank, Trey’s father physically dominated any space he occupied. Standing at 6-feet-4, he was muscular and lean with powerful shoulders and big gnarled hands. His body had been molded by years of hard work. He’d had more contact with animals, with reins and ropes and weather and solitude, than he’d had with people. All the years at that life had molded his temperament, too. Little Frank was a man of few words. He was strong and kind in his way, but communication wasn’t his strong suit. He wasn’t an easy man to know.

Trey’s mother, Claudine Abernathy Henry, was a different species. There was no guessing about her intentions, where she stood on a subject or what she wanted. Opposition was a stranger to her. Claudine always prevailed, regardless of the circumstances or hurdles thrown in her way. Almost always. Her marriage to John Francis Henry, Jr. was a notable exception—but if it hadn’t been her heart’s desire, she’d made the best of it. Pragmatism was high on the list of her characteristics.

Her mother and father had deep roots going back generations, when their hardscrabble forebears homesteaded cruel, dry land, “proved it up” and made a go of it, turning it into the sizable Ten Twenty Ranch that abutted land owned by Big Frank Henry. That’s where Claudine grew up. Her daddy, Claude, liked to say she rode a horse before she could walk, a claim that was only slightly exaggerated. By the time she was two years old, the only thing that could please her, stop her crying, was to be placed in the front of her father’s saddle astride his big horse, clutching the saddle horn while he worked cows. Only after she became exhausted and limp, keeled over Claude’s big horse’s neck, would he lift her down and place her in the arms of a ranch hand to deliver home to her mother.

Claudine’s parents had a baby boy when Claudine was just shy of three years old. Her mother was fragile after his birth and having the willful Claudine off her hands for a few hours a day was a relief—and proved to be lifesaving for the little girl. Just after noon on a cold autumn morning, Claude’s ranch hand rode up to the house to deposit Claudine and saw the ranch house ablaze. He was able to pull mother and baby out before the roof timbers tumbled down, but the life was gone from them. Claude Abernathy buried his wife and baby son the same day, after which he put little Claudine on her own horse, the one he’d given her for her fourth birthday, and they spent the rest of that day working cows—pragmatically doing what had to be done.

Claude raised his daughter with the help of his spinster aunt Lou, who came from Oklahoma to help with the little girl and devoted herself entirely to her nephew and his little daughter for the rest of her life. Claude told Aunt Lou she was in charge of his daughter, but being in charge of young Claudine was a tall order. Lou did what she could to corral her willful great-niece, tried to instill some empathy, but sweet, caring Aunt Lou had her hands full.

Claudine grew up strong and independent without the expectation that life would be handed to her without something given in return. But when she was just 16, she allowed herself to indulge one soft spot—a cowboy who worked for her father on the Ten Twenty. Then, like many of her friends in Dixon—the daughters of wealthy families—she went away to school back east. But after only the first few weeks away, Claudine made her mind up that she would come home and marry the cowboy she loved.

It was the rare and notable occasion in Claudine’s life when she did not prevail.

Claude had other plans, and when Claudine returned home for the Christmas holidays that year, her socially insignificant cowboy was gone and the subject of him was closed. She found a scrawled note on her pillow, a note the young cowboy had left with her Aunt Lou. It read, “My dearest girl Claudie, I will love you always.” Claudine Abernathy married her neighbor John Francis Henry, Jr. as her father expected her to do and made a life with him. Eventually, they merged their inherited ranches.

Claudine kept the cherished note from her cowboy stowed inside her jewelry box. She only ever read it one time, but over the years, from rare time to rare time, she took it from underneath the velvet lining of the box, turned it over and over in her hands and felt a pang of regret mixed with a deep gratitude to her Aunt Lou for passing it along to her.

Within a year of her son Trey returning home from Europe, another letter would join the old, scrawled note from her cowboy, and together they would lie in secrecy, tucked away under the velvet lining of Claudine’s jewelry box.

That same year, after Trey’s return from fighting a war, he delivered a rare defeat to his mother. The union of Claudine’s son to a carefully cultivated young woman failed when Trey followed his own mind in a way Claudine had been prevented from doing.

Trey had rekindled a relationship that began when he was so young, he didn’t remember its origin. Late one afternoon, Trey was on his way from the feed store back out to the Ten Twenty with a load of horse feed in his pickup when he pulled into Harshberger’s Bakery. Trey’s stomach was making insistent noises, and he realized he hadn’t eaten since breakfast. The huge cinnamon rolls that Otto and Emmie Harshberger turned out called his name.

Lara Becker was bent over with her head inserted deep into the bakery case collecting doughnuts, Danish and cookies that she boxed up every day before closing time and placed next to the Day-Old sign by the cash register. When the bell on the door clanged, she peered through the glass case and couldn’t quite make out who it was that strode in so late in the afternoon. Trey looked around but didn’t see a soul there until he glanced through the glass and saw Lara. Her features were distorted by the glass. It took him a moment to recognize her. It took her a moment, too, to recognize him, and when she did her face warmed and turned a little pink. "Trey Henry, of all people,” she thought. Her pulse quickened. With as much nonchalance as she could muster, she stood to face the now-grown man she’d been smitten with since they were in kindergarten class. “May I help you?” she said casually. A shard of doughnut glaze was stuck to her dark hair. Trey reached across the counter and removed the stuck-on sugar glaze. Her pink cheeks turned scarlet. “Lara Becker,” he scolded. “Don’t you recognize me?” Her pretense melted away along with the years since she’d seen him. She ran around the counter, threw her arms around him and sighed into his ear, “I heard you were back and in one piece. Thank the Lord.”

They were together every day from there out despite Claudine’s efforts to discourage, even sabotage their togetherness. Her notion of a suitable marriage to the prominent young woman she’d cultivated and images of a grand wedding dwindled and evaporated utterly as she sat in the front pew of the Methodist Church watching her son repeat wedding vows to the socially insignificant Lara Becker. The Henrys hosted a modest and blessedly brief reception at the ranch. Little Frank was unusually warm and inviting to his new daughter-in-law, possibly to counterbalance his wife’s undisguised disappointment and disapproval.

Trey and Lara made a hasty exit the minute they politely could and headed out on a brief honeymoon trip to the mountains. They spent just a few carefree, cozy days in a rustic but charming cabin secluded among giant, fragrant pine trees. At night, wood popped in the fireplace.

The couple talked and laughed, made plans and hatched dreams—about the home they wanted away from the Ten Twenty, about traveling to some of the places Trey had seen during the war and, more than anything, about the family they wanted and which, unbeknownst to anyone but themselves, had gotten a head start on. In six months, they would have a baby girl.

The honeymoon was in stark contrast to the life the couple took up when they returned to the Ten Twenty. Trey went back to work daylight to dark with his father while Lara did all she could to help run the house, making every effort to please Claudine or at the very least not displease her—a wasted effort that became more futile after the unwelcome news of Lara’s pregnancy was revealed. Claudine’s ire was palpable. She made no attempt to conceal her displeasure, which increased as the weeks and months passed. In every way possible, Trey tried to soften Lara’s circumstances. At night, the two of them escaped the obligatory family dinner table as soon as they could to retreat to their own room and conspire again about the future and their excitement about raising a child together in a home of their own.

A month before the baby was due, Trey was pressed by his father to accompany him on an overnight trip to tend to ranch business. He was reluctant to leave Lara for even one night but—well, duty called, and his father hadn’t actually asked.

Lara was standing at the kitchen sink shortly after they left, looking across the pasture that connected to other pastures of the Ten Twenty Ranch. Lara allowed her mind to wander to thoughts of the future but was jarred back to the present when the impatient baby in her belly kicked so hard, Lara could see the pattern on her cotton apron move. She let out a gasp, followed by joyful laughter that could be heard all the way to the room where Claudine was talking on the telephone. When Claudine went to see what had gotten into her daughter-in-law, she saw Lara standing at the sink smiling and pressing her hands against her bulging belly. Lara forgot for a moment that her joy was not shared and said, “Oh, Claudine, come feel my belly. This baby’s kicking like a bronco!” Claudine’s face was granite. She turned and left Lara in the kitchen alone. Claudine and Lara shared an uncomfortable meal that evening. Then, abruptly, Claudine left Lara to clear the table and went to her bedroom.

Lara was anxious for Trey’s return the next morning. Exhausted both physically and emotionally, she started down the hall to bed when she heard Claudine’s voice ring out brusquely, instructing her, “Come here, Lara. I have something to show you.” Lara sighed, closed her eyes and considered ignoring Claudine. Instead, she steeled herself and went to her mother-in-law’s lair. Claudine was sitting at her dressing table, watching in the mirror as Lara entered the room. Claudine fixed her gaze on the open jewelry box where she had lifted the velvet lining. Awkward moments passed. Claudine motioned for Lara to take a seat on the bench at the end of her bed. She picked up the jewelry box and walked to where Lara was seated. She placed the box between herself and Lara. She had an envelope in her other hand. She removed a single piece of paper from it and began to read the words on the onionskin page, words that had been written a little over a year ago, words that struck Lara through the heart.

Dear Mrs. Henry,

I am sending to your address a letter with news for your son Trey in the hope you will tell him of our circumstance—that of my father and mother and myself. Father is ill as is Mother, but more important we are alive and together at last and forever thankful for the kindness your son showed to us. The most important thing I have to say is the news that I have given birth to a baby, the baby of your son. We are in extreme and dire circumstance as there is little food here and our home in ruins. Please if you can and I ask only little—send money for us to buy food, live some longer and feed and care for my baby, the baby girl of your son. I ask only for her. I must keep private that my child is not German as conditions for children of GIs is not good. I believe your son will want to know this news.

Very sincerely,

Edda Maria Huber

Claudine folded the letter, replaced it in the envelope and turned to Lara. “I want you to know, Lara, that I have sent money to the woman and will continue to do so with the understanding that Trey is not to know. Now or ever. I’ve kept my son’s bastard child a secret, and I intend for you to do the same. And remember, Lara, that yours will not be the first child belonging to my son. Yours will be the fortunate one. I expect your promise on this, Lara. Now, go on. I want to go to bed.”

With a strength from somewhere, Lara walked out of Claudine’s room down the hallway to her bedroom. She fell onto the floor as if she had been bombed, shelled, attacked and left in ruins. In the early hours of that morning before Trey and his father returned home, she went into labor. Lara laid in agony for hours, unwilling to call out to Claudine. Trey returned to find her exhausted and ready to deliver.

Lara gave birth to a healthy, strong baby girl. A baby girl she hoped would never suffer deprivation or war or the absence of her father. She kept the secret. She swallowed the malevolent intention behind its revelation. In Lara’s mind, she had nothing to forgive Trey for. But nothing would ever soften her heart toward Claudine for trying to destroy her, for trying to sow division between her and Trey. Lara and Trey watched their little girl grow and thrive. Over the years, Lara read news articles, anything she could find out about conditions in Europe in the aftermath of the war. The facts were grim. The German people endured unfathomable hardships as they tried to restore life after the destruction visited upon them when the Allies overthrew the Nazi and Fascist threat to the world. Lara had to trust that Claudine would keep her word to continue to send funds to provide for the child.

Claudine’s Aunt Lou was still living and lent her sweet hand to help raise Lara and Trey’s little girl, just as she had helped Claude raise Claudine. Trey and Lara named the little girl Frances Lou after his daddy and his aunt. Claudine became ill not many years later. By the time the pain she’d ignored for too long was diagnosed, malignancy had spread through her body. She laid in her bed surrounded by her family. She looked at each one, seeming to impart last words she was unable to speak. Even though Lara hung back from her bedside, Claudine’s eyes searched the faces in the room until they lit upon Lara’s. With all the silent intent she could muster, she willed Lara to remember the poisonous promise she’d forced upon her. In that moment, Lara’s eyes delivered a silent but unmistakable response that she would no longer be bound by Claudine’s dark demand.

As she wished, Claudine was buried the same day she died, just as her mother and baby brother had been and as her father Claude had been. Afterwards, Lara strode into Claudine’s bedroom and straight for the jewelry box. Tearing back the velvet lining, she expected to find the letter. It was gone. That night, Trey Henry found two envelopes tucked under his pillow with a note in his Aunt Lou’s hand reading, “Dearest Boy, you deserve to know. Love, Aunt Lou”

It took decades to find her. When Claudine Henry died, she took all the information about the child with her to the grave. Lara was as resolute in the search for Trey’s child as he was. At last, an answer came. By then, Trey was 88 years old. He and Lara traveled to Europe together. Fittingly, it was in November, the weekend after Thanksgiving, when Trey laid a wreath on the small headstone that marked the grave of his long-lost daughter.

He laid a rose on each of the graves surrounding hers, one for her mother, the German girl he’d known as a young GI so many years ago, and the graves of her parents. Standing there in the cold as a light snow began to fall, John Francis Henry III wiped away a tear and said, “Little one, I’m your daddy. I’d have been here sooner if I could.”

Share this post