Fortunately, Ike remembered he had an old pair of work boots in the back of his pickup. It was the only thing he could think of that might give his tires enough traction to get unstuck. After so many attempts, the tires had dug deep trenches in the soft dirt. He wedged a boot under each of the back tires, then got back in the cab and started the engine. Hanging his body halfway out the driver’s side door and watching the rear end of the pickup to see if he was making any progress, he stepped on the gas and gradually accelerated. As the engine wound up, the tires ground into the boots and dirt, then lurched forward.

Hot and thirsty, he pulled on the emergency brake and let the engine run while he went around to the bed of the pickup where he kept a galvanized steel, five-gallon water can. He took a cone-shaped paper cup from a stack, filled it to the top with ice-cold water from the spout, drank it down, then crumpled the cup and tossed it into the bed of the pickup. He took the big metal lid off the water can. The lid was deep and held a lot of water. Ike filled the lid, took another deep drink of water, then poured the remainder over his neck. The water spread across his broad shoulders, turning the tan of his khaki shirt to dark caramel and sticking it to his back. He looked out across the Llano Estacado where a flat line of blue sky met brown earth as far as he could see. He closed his eyes and took another breath—deep and long—until his lungs felt as wide and clear as the landscape that stretched out before him. Ike was shaken up by the mishap. Normally, he was alone on the job—just him and the feisty black-and-white terrier Midge, who never missed a day of work—but on this day, when they had very nearly gotten stranded miles and miles from anywhere, Ike and Midge had company.

Ike took several more breaths before he filled the lid again and carried it to the passenger side of the pickup where his only child, eight-year-old Priscilla, was sitting holding a dead quail. She was unconcerned about their predicament with the pickup, she was so intent on trying to make the bird’s limp head stand upright. Several times, she had positioned the tiny head to an upright position, and each time she let go, the little head fell loose again, back to the side of its body. It fell more heavily than seemed fitting for such a small head. Dead weight. And growing inside her, Priscilla felt the dead weight of regret.

It was a school day, but Priscilla’s parents had allowed her to take the whole day off. It was just a week and a half before quail season was over, and Priscilla had been asking to go quail hunting with Ike. Ike and Jerry Dale had talked it over and decided it would do her good to get away, out where she could clear her mind. Something bad had happened to Priscilla, something that had turned her eight-year-old world upside down.

Early on that cold February morning while it was still dark outside, Ike followed his usual routine. He stowed his lunchpail behind the front seat, tucked a thermos of hot coffee under the seat within easy reach and laid his flannel-lined jacket next to him on the bench seat for Midge. The little terrier leapt into the cab and rared up on the dashboard, her hind legs stretched out as far as they could go to reach. She would ride this way until they got out to the highway past the city limits west of town. When she was satisfied they were on track, she’d tuck herself close to Ike’s side and curl up on the jacket he’d laid for her. Priscilla walked stiffly out to the pickup. Jerry Dale had her bundled up so tight in her beige car coat she could barely walk. The hood was drawn up and gathered around her face until her eyes were almost covered, so she had to hold her head way back to see where she was going. Ike called, “Come on, Nubbin,” and held the door open. Priscilla climbed into Ol’ Red and took her place at shotgun. Jerry Dale held back the drapes that covered the picture window in the living room and watched the pickup disappear in the cloud of vapor that roiled out of the exhaust pipe in the early, frosty air.

Before leaving town, Ike always stopped at the icehouse to tend to his water can. Even when it’s cold, cold winter, it’s critical to have plenty of water out on the far-flung oil leases miles from town. When Ike pulled up to the loading platform at the icehouse, he gave a short honk signaling Sam Trout of his arrival.

Trout Ice Company was on the highway past the fairgrounds, just outside the city limits. Sam started working there when he was not quite eight years old, younger than Priscilla—or Little Ike, as Sam called her. Sam was an orphan and lived with first one, then another, of his kinfolks up until Old Mr. Atkins, who owned Dixon Ice Company, let him live in a little house out behind the icehouse. The little house wasn’t more than about eight-by-eight, but it suited Sam and all the dogs he had over the years. The dogs were named Dog One, then there was Dog Two, Dog Three and so on.

Mr. Atkins looked out for Sam, pretty much raised him as much as Sam would let him. Sam refused to go live with Tom and Thelma Atkins in their big house in town. Sam said he knew his place even though the Atkins assured him he would be safe under their roof. Tom and Thelma never had children, and when they died, they left the icehouse to Sam Trout. Sam served with the Harlem Hellfighters in the Great War and had come back from France nearly blinded from mustard gas. But he knew his way around the icehouse and went straight back to work for Mr. Atkins, still refusing to move inside the city limits. Sam was born independent— “independent as a hog on ice” he was used to saying. Priscilla had never seen this hog, could only imagine it tromping around on big blocks of ice somewhere inside the icehouse. It bothered her some, but she decided if it didn’t bother her daddy, she wouldn’t let it bother her either. She also figured her mother had no idea about this independent hog on ice—another reason to keep it to herself.

Priscilla had known Sam Trout for as long as she could remember. She liked to go with Ike to visit him and have coffee. Priscilla learned to eat fruitcake at Sam’s. She never learned to like it, but she learned to eat it. Sam always served her and her daddy a slice when they stopped by. Claxton’s Fruitcake. According to Sam, it was the only fruitcake fit to eat.

For as long as Priscilla could remember, she was amazed at how Sam Trout could live in such a tiny house. But there wasn’t a thing he didn’t have and wasn’t able to put his hands on. Every inch of space provided a specific place for everything. Shelves ran up the walls and were stacked with cigar boxes and fruitcake tins filled with necessities. The walls had cracks that let in the wind, so Sam had covered them with newspapers and pages from magazines, creating a kind of time capsule. Priscilla didn’t know if it was polite to read someone’s wallpaper, but she did. Even the ceiling had hooks hanging down at different lengths. A tea kettle hung on one, a heavy cast iron skillet on another. And books—must have been over a hundred books arranged in neat rows all the way up to the ceiling. His books covered every subject Priscilla could imagine, and he loaned them out to anyone who was interested. Sam was superstitious, too, and there were rabbit’s feet nailed up all around the room and a horseshoe over the door. He kept a tow sack filled with silver dollars stowed behind the front door. Once in a while when Priscilla and Ike were there, he’d take one out of the big coins to show Priscilla.

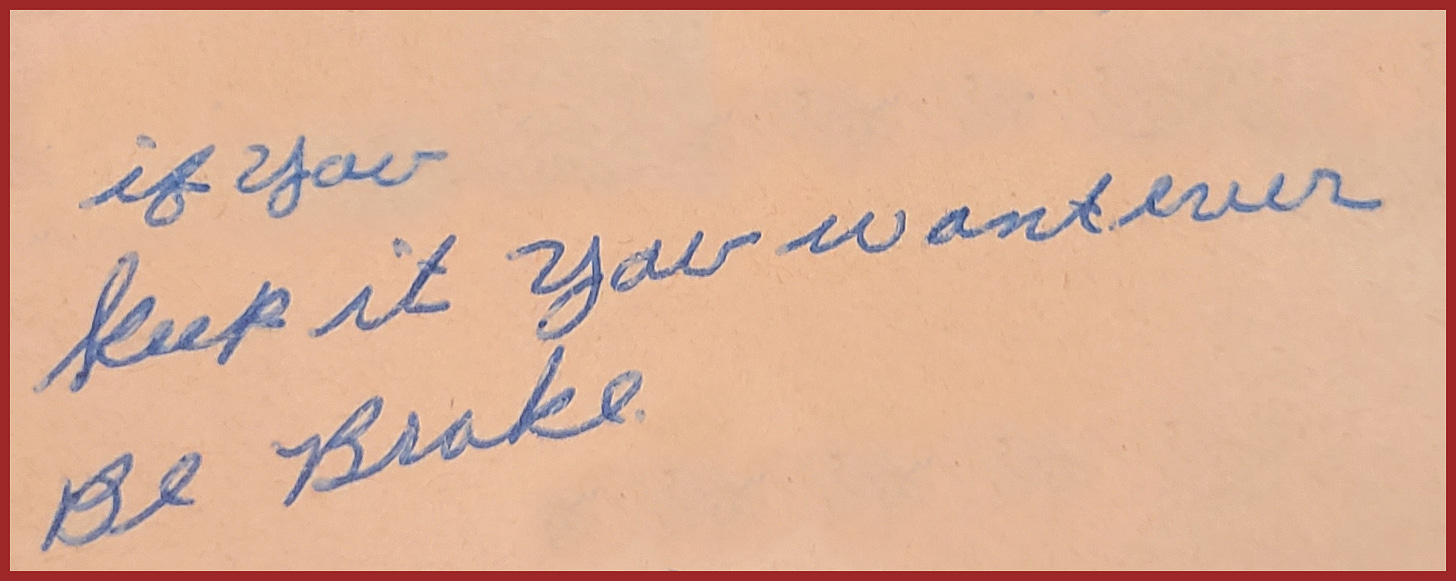

Holding it right up close to his eyes to make out the engraving, he would remark on the year it was minted and what had been going on in the world that particular year. Then, every so often, Sam Trout would press the silver dollar into Priscilla’s small hand and say, “Little Ike, you take this one, and if you always keep it, you’ll never be broke.”

That cold morning at the icehouse when Sam heard Ike’s honk, he poked his head through a narrow slit between two huge doors that hung on heavy metal rails. He flashed a wide grin that lit up his face and made his eyes crinkle. When he saw Priscilla lumbering out of the pickup, he let out a howl of laughter and said, “Little Ike, you’re lookin’ like a trussed-up pig in that coat.” “Pig,” she thought, and her mind went to the problematic hog on ice behind those heavy doors. Ike lifted her up and sat her on the edge of the concrete platform and went to get his big water can. Sam disappeared inside and came out carrying a heavy block of ice with a pair of huge tongs.

There were deep scrapes on each side of the ice block, scrapes made either by the tongs or the hog hooves—Priscilla didn’t know. Sam eased the block into Ike’s water can, topped it off with a hose, then loaded it into Ike’s pickup. Ike motioned to Priscilla, saying, “Come on, Nubbin, let’s hit the road,” and lifted her into the cab. Sam gave a knock on the side of the pickup and waved as they pulled away. Priscilla turned around stiffly to look back and wave until her breath fogged up the window and she could no longer see Sam and he could no longer see her little cinched-up face.

Ike drove past the old Shaw place that was falling to staves, past the tiny airstrip where an orange windsock was almost always blowing straight out, past the little herd of antelope that grazed a pasture west of town. Finally, Ike turned off the highway onto a web of narrow roads that led across ranchland to the gravel-covered areas where oil companies had erected pumping units and tank batteries and other immense pieces of machinery to extract the black oil and natural gas that lay beneath the earth. Once unnatural looking, over the years the oil wells blended into the landscape—just as the once unnatural-looking wooden windmills that extracted groundwater from deep aquifers had done—just as barbed wire fences had done and metal cattle guards that kept the cows from going astray. These things represented progress for some and the end of a way of life and land for others.

If it wasn’t too cold or too hot or the wind wasn’t blowing too hard when Ike and Priscilla and Midge got to the lease, Ike might let Priscilla get out and climb the metal ladder to the top of the tank battery to walk along the catwalk that ran the length of the row of tanks.

She’d watch as Ike opened up the hatch cover and dropped a heavy, pointed, brass plumb bob down into the tank. It made her shudder, imagining the plumb bob descending down, down, down to the bottom of the huge tanks filled with thick crude oil. Ike would wind the apparatus back up, check the reading, then jot down figures into a small notebook while Priscilla leaned on the metal railing looking out across the prairie.

Like her daddy, Priscilla could always spot an animal anywhere, and from way up on the catwalk, it was even easier to spot jackrabbits and cottontails. Sometimes a slender antelope would stand frozen, its eyes fixed on Priscilla’s eyes, then be gone so fast it barely kicked up a puff of dust. She stayed on the lookout for jackalopes, too. Someday, she believed, if she looked hard enough, she’d spot one.

Climbing down, the metal rungs sent pings reverberating along the metal railings. “Be careful now, Nubbin, watch your step.” Ike framed his arms around her, protecting her as they made their way down. Once back on the ground, they’d go to what was called the doghouse. It was a small building with a desk where Ike kept logbooks with long columns of figures representing the amount of oil in the tanks, the results of tests for the quality of the oil, and figures from transporters who’d pumped oil into trucks and hauled it away down the caliche-covered road and off to refineries. There was a space heater that hummed on cold days, the bright orange coils making the room toasty. After a while, Ike would clear off a place on the desk and bring out his big silver lunchpail, and father, daughter and dog would enjoy bologna sandwiches, pickles, Fritos and black coffee from a thermos, finishing off with pink Sno Balls. Sitting on the floor, Priscilla almost ritually unwrapped the cellophane that enclosed the pink coconut-and-marshmallow-covered chocolate cakes that sat side-by-side, two to a package on a white cardboard tray. Thinking they looked like small pink clouds, she’d bite deep into the cream-filled center, causing coconut flakes to fall like pink snow onto the uneven planks of the floor. Midge would clean up the flakes, missing a few bits that fell through cracks and landed on the dirt below the doghouse, leaving morsels for field mice.

On this particular day, even before his pickup got stuck in the dirt, Ike was uneasy. He was concerned about his little girl and what had happened to her at school. And he had some misgivings about the promised quail hunting. Fried quail, the way Ike cooked them was one of Priscilla’s favorite meals. Ike knew Priscilla would be disappointed if they came home empty-handed, but he also knew she had a child’s limited understanding of exactly how the food chain worked. On the seldom occasions when he brought home a few birds, he made sure to clean and pluck them out by the trash barrels in the alley away from sight—careful not to let Priscilla catch a glimpse of the gory job. Her only experience with the birds would be when she bit into the tasty fried meat alongside rich brown gravy made from the pan drippings and poured over biscuits and fried potatoes.

So, when they started for home, Ike’s instinct was to pretend not to see the covey of quail just off the road, scratching around in a stand of shinnery oak. But Priscilla’s eaglet eyes spotted the birds, and he was obliged to pull over. No doubt it was his preoccupation with so many things that caused him not to notice how soft the dirt was on the side of the road.

One blast of his shotgun brought down half a dozen birds. As he always did, he felt some regret at having shot an animal. He carried the small, feathered bodies back to his pickup. Priscilla waited for his permission, then leaped out of the pickup to see. She eagerly took one of the now-limp birds in her hands. The unmistakable reality took her breath away for a few seconds. She cradled the quail in her small hands, carried it back to the pickup where she sat quietly. The little neck failed to hold up the tiny head no matter how many times she tried. She was oblivious to the fact that they were stuck in the soft dirt. She had no idea they could be stranded. No idea that in an hour or so, darkness might surround them. Priscilla knew about death, though, for the first time.

It was just a couple of days before that Jerry Dale had gotten the call from the school. Priscilla’s teacher wanted to meet with her. Jerry Dale took off work early and was in Miss Houghton’s office exactly at 4 p.m. Her mind had been in overdrive trying to anticipate why on earth Priscilla’s teacher had summoned her. She and Ike had stayed up late into the night considering everything they could imagine.

When Jerry Dale arrived at the school that next afternoon, Anne Houghton greeted her at the door of her classroom. She offered perfunctory pleasantries and indicated a child-sized seat for Jerry Dale opposite her full-sized seat. Then she launched into an explanation of the problem.

She had focused on each of her pupils, one by one, to discern their particular weakness. She believed that highlighting a child’s weakness was the best way to encourage the child to improve. She said she had easily been able to identify the main weakness in each child in her class.

Jerry Dale’s hackles began to rise as Miss Houghton continued. First, the teacher lavished praise on Priscilla, remarking that she was smart and poised, got along well with the other children, participated in class, always finished her work on time, had excellent grades, was confident and perfectly behaved. She went on, saying, “And Priscilla is such a pretty little girl, too. Beautifully dressed and groomed. But Mrs. Gibson, I simply cannot understand it. I have been able to make every other child in my class cry with the exception of your daughter.” Incredulity smacked Jerry Dale in the face. Barely able to catch her breath, she continued to sit in stunned silence, anger rising like magma ready to spew. She staunched the urge to slap the woman across the face. Instead, she rose calmly and silently, picked up her purse from the tiny chair and replied evenly, “You will never make Priscilla cry. She’d have to like you first.”

That night, after long, serious conversations, Ike and Jerry Dale told Priscilla she could stay home from school and spend the day quail hunting with her daddy. And they told her it would be her decision if she wanted to stay in Miss Houghton’s class or request another room.

Priscilla never told her parents about the day her teacher called her to the front of the class—in front of all her friends and classmates, many she’d known her whole eight-year-old life. Their parents were friends of her own parents. Priscilla had not told Ike and Jerry Dale about how puzzled and self-conscious she felt as her teacher began to explain to the class that Priscilla was an Only Child, the only Only Child in their class. Priscilla felt her ears sting as Miss Houghton went on explaining that, as an Only Child, Priscilla’s achievements counted less than their achievements. Because Priscilla’s parents had only one child, they were able to devote more time to her, give her more advantages. With only one child, they could lavish her with unlimited time and attention, giving Priscilla an unfair advantage. But there was no doubt that it would cause Priscilla in the long run to become spoiled and irresponsible, and the Gibsons would fail Priscilla as parents.

The pain of having her parents unfairly criticized was unbearable to Priscilla. She made up her mind to prove this woman wrong. And the decision about whether to stay in Miss Houghton’s room was: Stay. Priscilla may have only been an eight-year-old child, but weakness was not in her makeup.

However, Anne Houghton had rooted out a weakness in Priscilla. Anne Houghton had watched her with Ike and Jerry Dale. She’d seen her in the morning when Jerry Dale dropped her in front of the school. Watched as Priscilla hesitated, turned back to give her mother another wave. She’d seen how Jerry Dale watched and waited until Priscilla completely disappeared into Room 307. Miss Houghton had seen Priscilla’s pace quicken in the afternoon when she saw Ike waiting at the curb in Ol’ Red, holding onto her little terrier to keep her from leaping out the window. Ike would call, “Come on, Nubbin Head,” and Priscilla would break into a run to join him. Ike and Jerry Dale lived in the softest spot in Priscilla’s heart.

Anne Houghton enjoyed the reputation of being the best teacher for gifted children at Beal Elementary, and when Priscilla was placed in her class, Ike and Jerry Dale were confident their daughter would excel and rise to the challenge. Although Miss Houghton wasn’t warm like the other elementary teachers, most everyone explained her personality by saying, “Well, you know, she’s not from around here.” When asked where she was from, she replied curtly that she was from “back east.”

When Anne Houghton came from “back east” to live and work in the small remote town of Dixon, she brought not only her New England sensibilities, both real and contrived, she also brought her longtime companion, Nancy Hughes. One could almost picture the pair standing, eyes closed, before a map of the U.S., jabbing a finger somewhere left of the East Coast, landing on Dixon and agreeing it was about as far away from disapproving and disowning families as they could get. Nancy Hughes was also an elementary school teacher. She was more outgoing than her companion and became well-liked around town. Anne Houghton’s attitude toward Dixon and the citizens of Dixon was almost palpably contemptuous. She was not well-liked.

She was a striking-looking woman. Her hair was salt-and-pepper, and she wore it swept back, emphasizing a pair of black eyes that could bore holes into any subject they became fixed upon. She had invested in a few tailored suits made in Boston. Classic suits that only required raising or lowering a hemline to keep them in style. She’d honed and embellished a story that included a Boston Brahmin family, a father who had served in the diplomatic corps and a childhood of fascinating experiences abroad. She spoke with an odd mixture of accents that she’d contrived to sound socially superior and polished, a way of speaking she picked up from her mother who had been trained as an actress to speak with a mid-Atlantic accent.

Anne Houghton was actually born and raised in South Boston and put herself through college working part-time and summers in her father’s package store. When she graduated from college, she and Nancy Hughes looked for a place that would put distance between them and their conflicted family relationships. The legendary Llano Estacado and the distant town perched atop those High Plains was about as far away as they could get. Both of them were hired at Beal Elementary. With their combined salaries, they bought a white brick ranch-style house.

And they found their individual niches. Anne joined the Episcopalian church. She enjoyed associating with the Epistocrats. Nancy joined the new chapter of the Pink Ladies Hospital Auxiliary. She enjoyed volunteer work and liked to be involved in community activities. As different as they were, they were a devoted couple.

Anne and Nancy were surprised when they learned another Dixon denizen hailed from working-class Boston—Pinky Dooley. Anne avoided Pinky, the popular proprietor of the Sundown Lounge. Dixon may be a long way from Massachusetts, but the world is forever small. Pinky’s little sister Bridget and Anne Houghton—the former Annie Hogan—took their first communion together at St. Brendan Church in Dorchester, Massachusetts. Pinky remembered little Annie Hogan well.

Nancy certainly did not seek out a friendship with Pinky Dooley either, even though he was known to be discreet. But occasionally when she stopped by the Sundown Lounge with her Pink Lady friends, she found herself wishing she could take a seat at the bar, reminisce with Pinky about their childhood. She liked the easy way he had with his customers. She liked hearing his easy laugh. It made her homesick and a little sad to have to keep up a charade she believed was not necessary. But she did. She loved Anne in spite of her insecurities. She knew the source of Anne’s insecurities and old scars.

Anne Houghton had just one friend in town, if you could call her that. Lydia Conroy. Lydia lived with her six children in a single-wide trailer house across the highway from Sam Trout and the icehouse. Lydia supported her kids by taking in ironing, and she was an expert seamstress—her work was exquisite. Anne Houghton employed her to keep up with any necessary alterations on her tailored suits. Lydia was grateful for the money, even if she became a helpless captive audience every time Miss Houghton showed up. Lydia and all six kids—Stephen John, 12, twins Walton Frank and Calvin Dale, 10, Carlene Suzanne, 8, Stanley Robert, 6, and little Callie Frances, 5—were obliged to sit lined up on the uncomfortable hide-a-bed in the cramped living room listening to Anne Houghton drone on and on, frequently for an hour or more, repeating stories about the privileged life she’d had growing up—stories so obviously fabricated even 5-year-old Callie Frances would roll her eyes and giggle until Lydia raised an eyebrow or pinched her on the leg.

Lydia had begun to notice that Carlene Suzanne—who was in Miss Houghton’s third-grade class with Priscilla—was unusually subdued when her teacher came to visit. If Lydia had had the time to so much as think about anything other than keeping her kids fed and clothed and a roof over their heads, she might have been more concerned about it. All Lydia thought to do when Miss Houghton left was to reward her brood for their polite behavior with extra goodies from a stash of off-brand cookies she kept high up in the kitchen cupboard.

Carlene Suzanne enjoyed visiting Sam Trout after school. When she got off the bus, she’d streak across the road to his tiny house and look over his books until she found something she liked—and she liked them all. Sam gave her fruitcake along with books. Without her knowledge, he had started a savings account for her college. Sam’s sight was getting worse, and Carlene Suzanne would sit next to him and Dog Four a lot of afternoons, reading aloud to them. She thought Dog Four preferred Louis L’Amour and Zane Grey novels over Sam’s classics. But lately, since the start of school, Carlene Suzanne had become troubled and avoided reading aloud to Sam. One afternoon, she was eating a slice of fruitcake when she began to cry. “Girl, what in the wide world is wrong?”

Between sobs, Carlene Suzanne said she was ashamed of her lisp and that she was dumb and worthless because of it. Miss Houghton had told her so.

And Carlene Suzanne wasn’t the only one. Terry, the sensitive little Sneed boy, had been made to stand in front of the classroom while Miss Houghton noted that he ran like a sissy on the dodgeball field. Bonnie Simpson, so fragile after losing her mother, was singled out for having messy hair, especially hurtful considering her father had taken so much effort to fix her hair in pigtails the way her mother had done. Scott Thomas developed a stutter. Priscilla Gibson was called out for the sin of being an only child. And Carlene Suzanne, who sat so still and quiet, grew more and more ashamed of her lisp after Miss Houghton described her as “too lazy to speak properly.”

Sam stayed quiet for a good while. Then he told Carlene Suzanne to go on home. He had something he needed to do. Seeing this little girl so hurt and hearing about the other kids made Sam as mad as he had ever been. “Four, come on.” His big dog jumped in the truck. Even though it was nearly dark—and Sam never went to town after dark—he headed straight to the door of Anne Houghton’s sterile-looking white brick house. One by one, child by child, Sam Trout confronted her with her unforgivable actions. He let her know that he might be an old, half-blind, Black man, but if he ever heard of her hurting another child, she’d have him to answer to.

With a few words from Sam when customers stopped by the icehouse, parents began to put the pieces together. Complaints were made. Pinky Dooley let word slip that the high-falutin’ Anne Houghton had grown up the down-at-heel youngest of ten Hogan kids from Dorchester, Massachusetts. Anne Houghton resigned. They lived on Nancy’s income alone. Most everyone avoided Anne. Except for Lydia Conroy. Lydia kept up a relationship because she was just too soft-hearted not to. Twice a year, maybe, she’d stop by the white brick house to visit a few minutes with the pair, see how they were doing and report on her family. Every one of her children had gone to college. Carlene Suzanne had been awarded a full-ride academic scholarship with expenses supplemented by an anonymous donor.

By the time Carlene Suzanne and Priscilla and all the other kids Sam watched out for, cared about and mentored were grown, his sight was almost completely gone, and “Ol’ Arthur,” as he called his arthritis, had gotten so bad he could barely get around on his own. Things in Dixon had changed by then, and Sam finally felt comfortable living within the city limits. He made Prairie View Assisted Living his new home. His room was more than twice the size of the little eight-by-eight house he’d lived in for decades. Ike visited him once a week, took him the pouches of Red Man tobacco he liked. They talked about the old days and the new days, talked about progress and how long it took to make any. They drank coffee, ate fruitcake, talked about Priscilla when she was a little girl and laughed about her theory about the hog in the icehouse. One of the nice volunteer girls read the newspaper to him, and Sam let her choose one of his books to read aloud from, too. After Priscilla was grown and had left Dixon, she always remembered Sam at Christmas and on his birthday. She sent him cards, and she always returned one of the silver dollars he’d given her when she was little with the note “If you keep this you’ll never be broke.”

Sam Trout did not die broke. He left over $100,000 in a savings account. In his will, he left instructions for Ike Gibson to take care of Dog Six, which he did. He also left instructions to use his life’s savings to set up a college scholarship fund for the children of Dixon. Sam left his collection of books to the school library, and ten years after Sam died, the City of Dixon constructed a new public library and named it for Sam. Sam Trout Public Library stands proudly on the corner of Central and Avenue D, inside the city limits and where—if you turn and head east—you’ll pass the old icehouse and Sam Trout’s little eight-by-eight house, still standing against all the wind that can blow.

Share this post