This story is different from the other stories in Corvairs and Horny Toads. It’s a true story. And I want you to hear it.

One day my mother, Billy Jo asked me to write about her cousin M.C. Griffin. He was a pilot in World War II and went on to have an illustrious Naval career. I began to write about Captain M.C. Griffin. Images of war planes—flying and diving, Griffins of all kinds and my mother—my tiny, brave mother and the women she and I descended from—went round and round in my head, sending me away to places I did not expect.

This is the story I wrote for my mother, Billy Jo Griffin Blackwood.

Her great form passed between the sun and the flat ground below and cast a shadow that floated over the house and yard that lay beneath her.

From high aloft, her green chimeric eyes, sharp and keen, took in everything directly below her and for miles in every direction. She cataloged each stone, each tumbleweed, every thorny mesquite tree and windmill and cow and lizard, prairie dog, coyote, snake and every child she was there to guard and protect, and committed it all to her infinite, immortal memory.

She alit on a tall thunderhead and sat upon her mighty lioness haunches. Her weighty talons and claws disappeared into the white vapor of the cloud. Still watchful, she began to preen the glossy feathers of her wings, loosening a single ebony feather that floated gracefully to earth, landing on the hard, dry dirt underneath a scrubby mesquite tree that had beetles and June bugs mysteriously impaled on the long thorns that ran along its skinny branches.

A dust devil corkscrewed across the yard, blowing dirt and debris ahead of its tall column, sending gusts of wind and disturbing one of the game hens that was scratching around in the yard for worms and bugs. The ill-tempered hen fanned her tail feathers and agilely dodged the column of dust before it could hit her full on.

Two little girls had their backs turned to the small violent wind phenomenon, their eyes covered to keep out sharp dirt particles and gravel. The skirts of their cotton dresses were plastered against their bodies by the wind gusts and outlined their small, thin thighs, giving a bit of protection, but their unprotected knees, calves and ankles were whipped and stung by the blowing sand and dirt. The littlest of the two girls, the one whose red hair was blown across her cheek and freckled nose, dropped the dowel pin she’d been holding. Bending into the wind, she strained to see through the dust, patted her small hand on the ground, feeling for the dowel pin, the weapon her daddy had given her, the weapon she used to beat back aggressive game hens that swooped in with fury to protect chicks. The girls let out high-pitched screams, as much from joy as pain because dust devils—like tiny pretend tornadoes—were exciting and fun.

When stillness returned, red-haired Billy Jo Griffin and her best friend Joanne Reeves ran across the yard to the mysteriously decorated mesquite tree. That is where they convened the irregular and haphazard meetings of their secret club, just two members strong. They had gotten the idea for their club from their daddies, who were devoted members of the local Masonic Lodge. The girls were fascinated by the secretive institution, and whenever they passed the impressive lodge hall, a big building on the corner of 1st Street and Central Avenue, they shuddered a little. God only knew what their daddies, both Master Masons and members of the Scottish Rite, got up to twice a month when they put on suits and attended meetings. Joanne looked forward to being a Rainbow Girl and eventually an Eastern Star when she was old enough, but Billy Jo had no interest in the women’s arm of the Masonic Lodge. The only thing that would have pleased her would be to become a full-fledged Freemason herself and to someday inherit the Masonic ring her daddy, John Calvin, wore, but she knew that was not possible because she had been born a girl.

The girls modeled the rules and bylaws of their club off the imagined rules and bylaws practiced by the ancient brotherhood their fathers embraced and revered. The first rule of their club, one of only two they had come up with, was all activities were to be kept strictly secret. The second rule: dues were to be collected at the start of each meeting. The dues consisted of one bug of any kind that must be impaled on a mesquite thorn as proof of payment. The second rule concerning the dues and the gruesome act of paying them was enough to keep meetings to a minimum. There was only ever one item on the agenda of their club’s meetings—what to play and how to keep all other kids out, especially Joanne’s baby sister June.

Poor little June. She was only a little thing, five years old. She tried her very best to fit in with the big girls, but she was exiled almost entirely from their strictly insular world, except on the days Billy Jo and Joanne played a game of The Katzenjammer Kids when poor June almost always ended up on the wrong end of their hijinks. Just a week ago, she’d fallen victim to their latest shenanigan when she answered her sister Joanne’s sweet call, “Hey, Juuuune, come ‘ere. I’ve got something to show you.” June had been sitting forlornly on the front porch step. She went searching for the big girls. Following her sister’s voice, she went down the side of the house and around to the back. She opened the screen door and stepped into the kitchen. The older girls’ Katzenjammer prank involved climbing a ladder and balancing a bucket on top of the door just right so when June opened the door and walked through it, the bucket tipped, and she was drenched in cold well water. The big girls laughed so hard, they keeled over on top of each other. Joanne howled and, with tears running down her cheeks, said, “June, you look like a drown’d-ed rat.” Little June managed to take some consolation as she sloshed her way across the yard, climbed up on a pile of lumber and sat there with the hot sun beating down on her and the wind blowing her face, thinking that even if she was the butt of the joke she was at least let in on some of the big-girl fun. It took the better part of an hour for her hair, dress, shoes and socks to dry.

The mighty Griffin had watched dispassionately as the prank unfolded. The girls were following nature, cruel as it could be sometimes, establishing a pecking order. There was no need for her to intervene.

On the day of the big dust devil, having finished her preening, the Griffin listened a while to the Ancient Ones—the ancestors of the children playing below. The Ancients had convened in a great hall in a realm where time and class did not exist, where warriors and sovereigns, lords and ladies, servants, serfs, coal miners and housemaids mingled equally together to commune, reminisce and look down upon their descendants. History chronicled the lives of many of the ancestors. Indeed, many of them had even changed the course of history, and by their existence the lives of the children who played below had been made better or perhaps worse.

Red-haired Billy Jo and the other children playing in the dusty yard below were unaware there was a realm beyond their own. Billy Jo’s older brothers J.C. and Buddy and their cousin M.C. were scuffling in the side yard. They’d locked horns over a game of marbles. One of the Ancients, the Griffin children’s Welsh ancestor Edyfyn Fychan watched awhile, pleased to see his young warrior descendants. He knew that one of them was destined to become distinguished in battle as he had been.

Edyfyn Fychan had attained high rank fighting battles in defense of Llewelyn the Great, first king of Wales, also an ancestor to the children. Llewelyn watched awhile, too—watched his descendants wrestling in the dirt over a handful of marbles. Perhaps there was no difference. Marbles. Kingdoms.

The Griffin did not ponder such trivial things as marbles or kingdoms, the past or the future. She knew both the past and the future. They were the same to her. Her duty, as it had been eternally, was to protect the children of the Ancients.

The Griffin had watched over young Edyfyn. She’d watched over young Llewelyn. And now she watched over young Billy Jo, her brothers and their cousin.

The Griffin knew that young M.C. would become a naval officer. She knew he would fly fighter jets in a great world war. She knew also that he would attain the rank of Captain, the only person at the time to achieve the rank without attending the Naval Academy. She knew that before he took command of his first ship, he would die in Naples, Italy, a continent away from his childhood home on the High Plains. She knew his death would be the result of head trauma. Trauma inflicted years before by the jarring stops he’d made landing fighter jets atop gigantic aircraft carriers to prevent them from tumbling into the deepest ocean on earth.

By centuries-old habit, Edyfyn kept his shield by his side. A family crest adorned the heavy shield. The crest had been designed by order of Llewelyn the Great to honor his fierce warrior Edyfyn. It bore the image of three helmets, symbolizing the three English noblemen Edyfyn had slain in defense of the king and whose still-bloody heads he’d presented to Llewelyn.

Although the children might never know the name of their fierce ancestor, Edyfyn Fychan was the father of the Tudor line. And through nursery rhymes and songs their mother Maude sang and recited, they knew something of the monarchs of Great Britain. At the end of every day when the chaos of their day had calmed, Maude had a habit of spending time with each of her children, time that was theirs and hers alone. While rocking them to sleep or tucking them in their beds, she would read nursery rhymes illustrated with brightly colored pictures of noblemen, knights, queens, kings, all the king’s horses and all the king’s men. Every child had a favorite. Freckle-faced Buddy begged to hear Old King Cole, especially the part when his mother tickled his ribs and whispered into his ticklish neck about “a merry old soul and a merry old soul was he.” Neither Maude or her mischievous second son knew that King Cole was the legendary Welsh monarch, Coel Hen, also an ancestor.

The Griffin knew, of course. She also knew that J.C., Maude’s oldest child—the serious, quiet one, the child Maude chose to tell stories of courage—would before long become very ill. The Griffin would watch as mother and son showed courage throughout the illness that would take J.C.’s life before his sixteenth birthday. Duty demanded the Griffin’s detachment. She seldom succumbed, but over the centuries, she had seen some scenes of grief so profound, they threatened to disrupt her detachment. It was then she found it necessary to hide a moment behind a black curtain, the feathered curtain of her great wings where she could regain her composure.

Red-haired Billy Jo, Maude’s oldest daughter, became lost in fantasies about the strong women in the stories her mother told. Billy Jo had no idea she was descended from fierce noblewomen. As the Baroness Maude de Braose watched the little girl, a subtle smile crossed her face. She knew her red-haired descendant, the little girl who played pranks and dreamed, would not be ruled by social mores any more than she had been centuries before. Medieval rules were meant to render even a baroness subservient. But Maude de Braose changed the course of history. The baroness contrived a scheme that freed the kidnapped heir to the English throne. She even avenged the death of her father, then celebrated her enemy’s death by hosting a celebratory banquet in her ancestral home of Wigmore Castle, where she displayed her enemy’s head on a pike.

Through force of will, wit and cunning, Maude de Braose became one of the most powerful women of her time. Would the little red-haired girl inherit her grit? The baroness knew she would. Maude de Braose had watched Patience Melinda, Billy Jo’s fearless grandmother, protect her children and her home. The baroness knew that ferocity flowed in her descendant’s veins.

Patience Melinda was mother to another Maude, Billy Jo’s mother Maude, who sang lullabies and read nursery rhymes to her children. Patience Melinda had known nothing of the other realm where the Ancients resided. She only knew that a half-dugout on a hard windblown homestead protected her three children from the elements and that she alone provided any other protection they had.

A trail half a mile from her dirt-floored home, the half-dugout, was frequented by men—cowboys from the nearby ranches, errant husbands from other homesteads, men who used the well-worn trail to get to the saloons and bars along the state line. With Maude’s father seldom home, Patience Melinda was left to make do. Cook. Battle the wind and blowing sand. Kill rattlesnakes.

It was washday. Patience Melinda was wrestling heavy men’s overalls onto a clothesline that was strung from a mesquite tree to the side of a corral. From the top of a small rise, a man sat astride a horse. His canny eyes assessed the simple homestead below as he decided on the kind of meanness he would visit upon a lone woman with three young’uns and not a sign of a man. The wind blew and whipped clothes in front of Patience Melinda’s eyes, blinding her for a moment. Little Maude’s even littler sister teetered toward the man, who was caught by the sight of the baby. The baby had a tiny, shriveled hand. She was jabbering and drooling as babies do, and she was waving at him with her little malformed hand. In the time it took him to bring his attention back to the woman, he was staring down the barrel of a shotgun. “I’m not afraid of man nor devil, long or short range. Ride on,” she said, leveling the words at him as surely as she leveled the gun. There was no doubt Maude’s mother—Billy Jo’s grandmother—would have killed the man. Centuries earlier, she might have displayed his head on a pike.

On the day of the big dust devil, Mrs. Filby stuck her head out the screen door and, in a voice loud enough to get the attention of the Ancients above, called for the kids to “Come on—your lunch is on the table.” Louella Filby had been persuaded to tend to the children of John Calvin and Maude Griffin while Maude went away to take the waters in Mineral Wells, Texas. Louella Filby was scrawny and high-strung and completely ill-equipped to manage the Griffin children, but she’d promised.

Louella nearly worshipped her mercurial cousin, could deny her no request. She stood by as Maude prepared to leave—admiring her, not envying her. Maude Griffin dressed in fashion that was almost out of place there on that dry, flat landscape, fashion that was incongruous with the homestead and dirt-floored dugout where Patience Melinda had raised her. Maude’s father had said when asked for her hand in marriage, “If you can keep her in shoes and silk stockings, you can have her.” The dress she was wearing came by mail order from an exclusive store far from where she lived with her husband and their children—children who came at a frequency that made her almost despair. Louella was holding the youngest, Eva Gayle, and saw a tear drop from Maude’s eye onto the baby’s fat cheek when she leaned in and left a fragrant kiss. Quickly though, she turned on a well-heeled foot and got into the car. She didn’t look back. Louella watched the car loaded with Maude’s suitcases take off down the road, turn east onto the highway and disappear out of sight.

Louella Filby and Maude were distantly related by marriage, an association complicated enough even the great Griffin above had to think a minute to sort out, but they had been friends, too, for many years, and Louella knew that Maude, for all her fine clothes and what seemed like indulgent getaways, had just about more than she could say grace over, to deal with her husband John Calvin and five children. Louella knew Maude had buried a sixth, a baby boy who’d lived just two months. The Griffin knew Maude would soon have another grief to face.

Even on the hardest days, Maude hid her grief with indulgence of her brood. And nothing was too much trouble for her if it pleased her family. None of her children liked milk, which she believed to be essential to their health, so she invented irresistible ways to get it down them. She soaked toast slathered with butter and coated in cinnamon and sugar. She poured milk into mason jars, flavored it with vanilla and sugar and shook it to make cold frothy treats. In the winter, if it snowed, she would take her biggest saucepan out to the deepest drift and uncover the most pristine snow to make snow ice cream. She let the kids take over the living room and make tents out of family heirloom quilts, line up dining chairs to form train cars, and do handstands, thudding against the walls over and over and over. Within a few years, when three more little girls joined the brood, she made matching dresses in multiples of five and, according to the color of their hair, used a different weekly rinse—lemon for the youngest, a blonde child named Martha June, vinegar for redheads Billy Jo, Eva Gayle and Marybeth, and coffee for her only brunette child, Annette.

It was on one of the days Louella was on duty that Billy Jo and her friend Joanne decided to play paper dolls. They took extra measures to keep Joanne’s little sister away while they enjoyed their favorite pastime. They swept out a squeaky, faded red wagon that had held a load of mud pies they’d made earlier and loaded it with scissors and glue, one of Maude’s good blankets to lay out on the ground and the Montgomery Ward catalog that contained pages filled with pictures of stylishly dressed men and women that the girls would cut out. They cut out clothes and pretended to take the well-dressed dolls to all kinds of to-dos—galas and parties wearing tuxedos and evening gowns, swanky restaurants, shopping sprees, even extravagant ocean cruises aboard the fabled Queen Mary. And always close by, the girls would place a feather to ward off little sister June who had a nearly paralyzing fear of feathers. Billy Jo kept a much-used ratty-looking feather tucked in with her paper doll stuff, but on this day, she was thrilled when she looked down and saw the large ebony feather lying underneath the mesquite tree, the black feather that had fallen from the glossy wings of the immortal Griffin. The Griffin knew that before Billy Jo turned eight years old, she would fly to June Reeves’ defense like a fighting hen when, on June’s very first day of school, bigger girls knocked her down on the playground. And that a mere six years later, she would become a young surrogate mother to her even younger siblings.

The long, hot weekend that had eight children—siblings, cousins and friends—under the nervous supervision of Louella Filby culminated in an event that would be burned into the memories of children, adults and the mighty Griffin above. With Maude out of town, John Calvin had seized on the opportunity to arrange a forbidden event—a cockfight. It took a day and a half to construct the prairie Colosseum where the blood sport, gambling and drinking would take place. When Mrs. Filby got wind of it halfway into the first day, she was frantic. As construction of the fighting ring went on, she paced up and down, wringing her hands, murmuring, “Oh dear. Oh dear. Lord help us.” But with no way to stop it and no way to alert Maude way off in Mineral Wells, she simply had to carry on the best way she knew how.

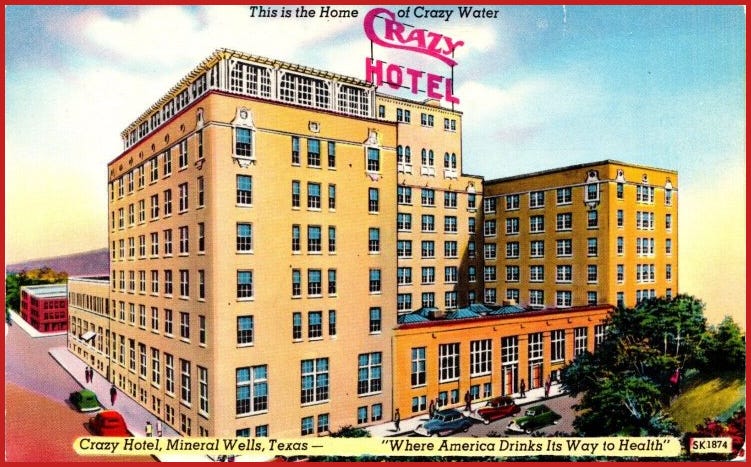

On that Saturday night, she situated herself in front of the big RCA Victor cathedral-style radio in the living room and tuned into her favorite show. It opened with a somber version of “The Eyes of Texas Are Upon You.” The announcer blew a train whistle and said, “How do you do, ladies and gentlemen? That was the Sunshine Special of health and happiness bringing you to Mineral Wells, Texas. This broadcast is coming to you right from the lobby of the beautiful Crazy Hotel. The home of our great natural product, Crazy Water.”

Mrs. Filby took a sip of the special elixir, Crazy, that Maude kept on hand on a high shelf in the kitchen cupboard. She visualized Maude at that very moment wearing her stone marten stole, seated in the ballroom of the Crazy Hotel listening to the Crazy Serenader and dancing in person to Jack Ablong’s Crazy Hotel Orchestra. By the time Mrs. M.D. Smith of Waco, Texas gave her Crazy Water testimonial about the amazing recovery she’d had from a debilitating malaise after using Crazy Water crystals for just one week, Louella took a big swig from her glass, closed her eyes and sent up a silent prayer that Maude would be similarly cured of all that ailed her and get back here to take over her houseful of unruly kids and sinful husband.

On that Saturday night, 327 miles away from her home and children, Maude closed her eyes. Her small feet floated across the ballroom floor. She placed a graceful, gloved hand lightly on the shoulder of the nice gentleman she’d met earlier in the day when she went on one of the many excursions that were offered by the hotel. He had come with his wife all the way from Oklahoma City in the hopes that the healing waters would cure her crippling arthritis. This wasn’t the first time Maude had been to Mineral Wells to take the waters. She placed a lot of stock in their healing powers. But whether it was the waters or the respite from the demands of her family, at that moment on the dance floor with the orchestra playing, she felt free and happy.

When Maude packed her bags and headed home the following afternoon, she was rejuvenated, ready to take up her life again. The Griffin flew above her, watching along the drive from Mineral Wells. With each mile she advanced westward, Maude became more excited to see her children and home. When she turned off the highway, the dirt road leading to the house was lined with cars and trucks. She pulled up in front of the house and parked beside her husband’s black Dodge pickup. She walked into the front door. Her footsteps echoed through an eerily empty house. She went to the kitchen, then out the kitchen door. The screen door slapped against the frame and sent another echo through the house. Then she saw the rough-hewn fencing that formed the arena. The Griffin felt her blood rise in tandem with Maude’s as the outraged wife and mother, heedless of her silk stockings and fancy shoes, marched across the dusty yard, out to where all the men and her own children were gathered.

Tiny red-haired Billy Jo never saw it coming. Her freckled nose was pressed against the chicken wire while she watched the horrible bloody fight. Her mother snatched her off the fence. Billy Jo’s fingers were so tightly squeezed in her mother’s hand, they had lost feeling by the time they reached the house, and Maude deposited her in the bathtub, saying, “Don’t you so much as move until I get back.” Billy Jo stood frozen and listened. She heard her mother’s heels stamping across the floor, then the sharp whack as the screen door slammed, followed by the unmistakable crack of a shotgun blast into the air.

The Griffin swooped and dove in the air. Her eagle screams echoed across the sky as she sent her mighty fury to pair with Maude’s. When Maude fired the shotgun into the air, it cut through the din that rose from the cockfighting ring. Men scattered. Cars and trucks tore out of sight. Then the race was on as Maude, a banshee, chased John Calvin around and around the ring, through the yard and finally to their car parked in front of the house. John Calvin flung open the driver’s side door and headed to the other side. Maude caught him by the shirttail midway and swung him around to face her. That was the moment Billy Jo saw with her own eyes. She’d gathered up enough courage to sneak out of the bathtub and peek out the front door in time to see her mother’s fist land right in the middle of her father’s face. A stream of blood spurted from his nose. She ran back to where she’d been told to stay and where she did stay frozen until her mother came back, stripped off her dirty clothes, scrubbed her down and roughly dried her off, scraping a perfectly good scab off her knee with a big bath towel. It hurt like hell, but Billy Jo did not so much as flinch. Maude managed to round up the rest of the kids—all except five-year-old Jerry, who she finally found squatted down by the side of the house with a big box of kitchen matches, striking them, watching the tips sizzle and flare, then pitching them under the house to conceal his crime. In that moment, the last drop of benefit she’d derived from the healing waters in Mineral Wells, Texas evaporated. Maudie Nell Maxwell Griffin collapsed on her bed and cried.

The Griffin alit on a high cloud. Louella Filby brought a wet rag and placed it on Maude’s head and began to unpack her suitcases—the dresses carefully folded between sheets of tissue paper, silk stockings, shoes, embroidered handkerchiefs and nightgowns. When she lifted Maude’s fur stole, the bright eyes of the stone martens had turned sad. And tucked away, Louella found a slick brochure from the lobby of the Crazy Hotel in Mineral Wells, Texas. The brochure pictured a serene, well-dressed woman relaxing in the ornate hotel lobby with a glass of Crazy Water. It described the sights and activities to be enjoyed, including donkey rides on the Texas Nightingales—which was what the donkeys had been nicknamed because of their singing voices—cable car rides to grassy parks with pavilions and bandstands, cafes, a merry-go-round and a casino. Movie stars and luminaries who frequented Mineral Wells were also listed and pictured—Clark Gable, Will Rogers, Tom Mix, Jean Harlow, the Three Stooges, Minnie Pearl and Judy Garland. Louella patted Maude’s leg and kissed her cheek and wished a wish that her cousin would be able to go back to take the waters again soon. Then she added to the wish that Maude would be able to find somebody else to come stay with her children if she ever did go back.

Painful and traumatic as the day had been for Billy Jo, it left a lifelong impression. She had witnessed her mother’s ferocity and learned from it. It served her well in life. She eventually had a daughter of her own and tried to pass along her mother and grandmother’s strength to her. Billy Jo built a career and rose to a position held mostly by men. On her first job at age 16, Billy Jo faced down a high-ranking officer at the airbase where she worked. When he brazenly cupped her breasts in his hands in full view of a roomful of other officers, she whirled around and in full view of those same officers slapped him across his face. The Griffin’s eagle scream echoed her approval. The Baroness Maude de Braose looked down at her 16-year-old descendent and raised a glass.

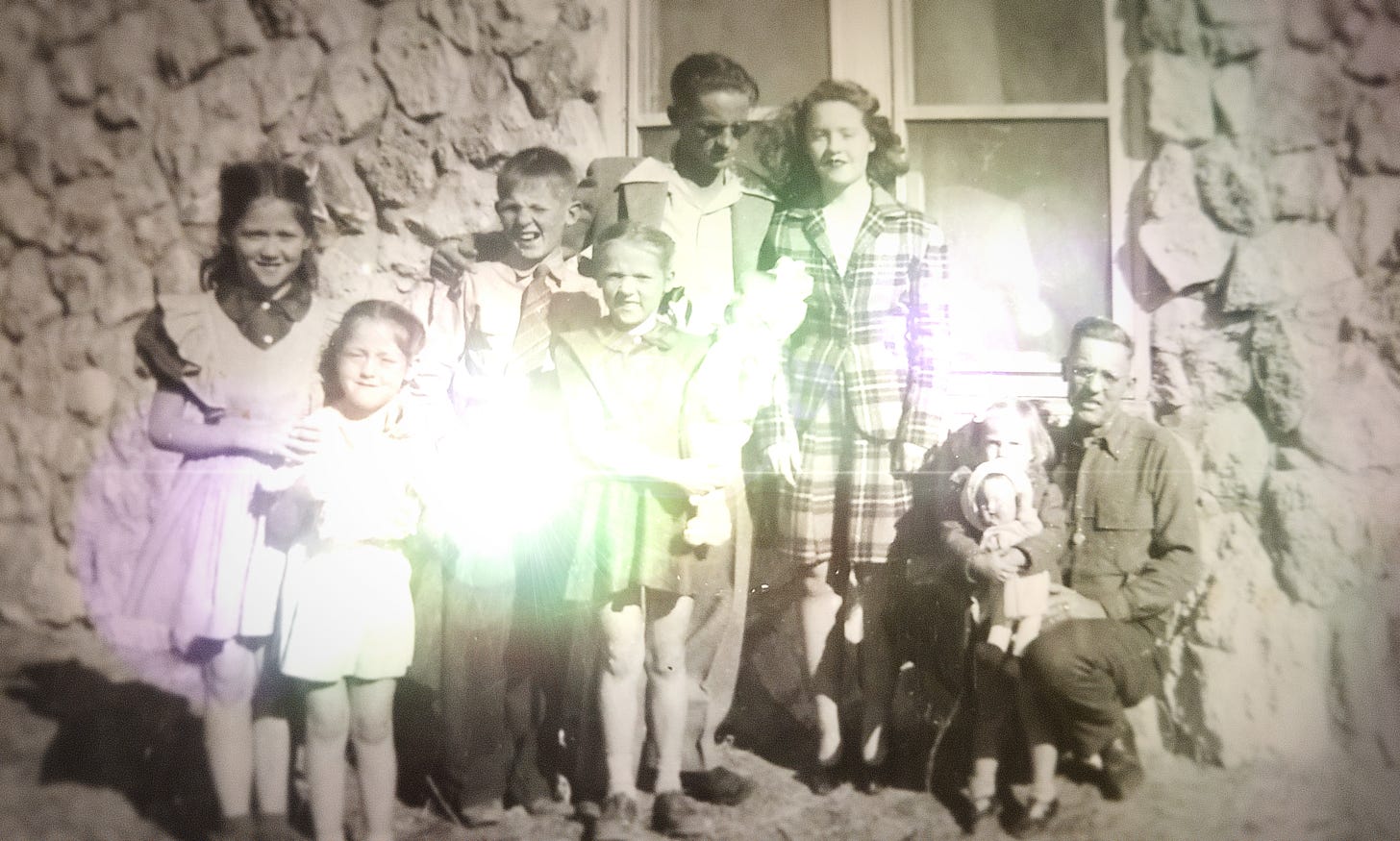

Two years earlier, Billy Jo’s mother Maude had died suddenly, leaving seven children motherless. John Calvin gathered his children together in front of their house in the country to have their picture taken. His second-oldest son Buddy, a man now, was home on leave from the service. John Calvin posed squatted on his haunches in the dirt with an arm around his baby, Martha, just 3 years old. He was surrounded by Billy Jo, who had become the young matriarch; Jerry, the firebug who was becoming a man before his time; Eva Gayle, unpredictable and verging on mania; Marybeth, posed with her baton; and Annette, the only brunette in the family, protectively holding onto a puppy. John Calvin had an expression of profound pain that was captured in black and white. It is a snapshot that forever reflects the face of a father and husband lost in sorrow.

Looking down at the family she was sworn to protect, the Griffin turned away for a moment, spread her gigantic ebony wings and wept. She regained her composure, then went for a while to sit among the Ancients in the other realm.

Share this post