In my story The Courthouse Squirrels, I describe the Pueblo Deco architecture of the courthouse. Studying that style, with its Native symbolism, made me delve into a troubling issue that happened in the pueblos of New Mexico: witch trials.

Yes, it happened in the Southwest just as it happened in Salem, driven by politics, religion and bigotry. New Mexico “witchcraft” referred to Indigenous beliefs outside the Catholic Church. The Church labeled these practices as witchcraft and punished practitioners harshly.

In Abiquiu, the trials involved the Genizaros, a group of people who were “In-Betweens.” Genizaros —a term no longer applied—were Natives of different tribes that had accepted affiliations with the Spaniards. Still, many Genizaros resisted forced Christianization. Father Juan José Toledo claimed the Genizaros of Abiquiu had cast a spell on him, which led to the trials and the severe punishments that were meted out by the Catholic Church.

At the Zuni Pueblo, witch trials took place all the way through the end of the 1800s. The notorious Sacred Bow Priesthood implemented the public torture and slaughter of “witches.” In the early 1900s—in a rare act of respect from the federal government—the U.S. ended the Zuni witch trials, enforcing laws that prohibited torture and execution.

Native symbols that were used in Pueblo Deco Style architecture—including symbols used by the Genizaros—were part of what created the outcry of witchcraft. These symbols can still be found carved in stone all over the Southwest. Some of these sacred symbols were desecrated. Some were removed entirely. Some were modified, overlaid with Christian symbols that were added during exorcisms. These Native symbols—later used as architectural motifs—represented paganism. These symbols were visual manifestations of obstacles the Catholic Church fully intended to overcome in its goal of conversion. There were souls to be harvested among the Indians, and the Church intended to reap the harvest by whatever means necessary.

When I was in junior high, the grandmother of my first cousins from a pueblo near Albuquerque died. Mama and Daddy and I traveled to the pueblo to attend the funeral. It was an experience I’ll never forget. The traditions that were carried on, the Native culture that was still present, made me feel a loss I couldn’t fathom. Why didn’t Daddy and I have this? What happened to us? Short answer: Indian Boarding Schools and Assimilation = Genocide.

We arrived after dark at the house in the village, the pueblo, and were welcomed into a cozy kitchen. Food was laid out on the table, coffee on the stove. A bowl of fragrant peaches cut up with fresh blackberries. In the adjoining room, the body of my cousins’ grandmother was wrapped in a blanket and laid out on the floor. Seated against the walls were family members and friends holding vigil. It wasn’t until then we learned that we were not supposed to leave the house once we’d entered it. But we did. We broke tradition.

I remember Daddy pushing open the screen door. I remember an animal sound, I think a dog. I remember crossing that threshold. I remember the cold. It felt heavy and forbidding and dreadful. I remember being scared. I knew Daddy was unnerved. But we walked out the door and returned to our hotel, even with misgivings. Even knowing that, by tradition, we weren’t supposed to leave.

But it wasn’t our tradition. What were our traditions, I wondered. I had a mixture of feelings. I thought we should belong, at least in spirit. But how could we belong? Even though Daddy and I were Indians, we weren’t Pueblo Indians. Right then, I didn’t feel like I belonged anywhere or with anyone. Not until it was just the three of us—me, Daddy and Mama—did I feel like part of a whole.

This brings me back to the Genizaros—the “In-Betweens.” They were a mixed-up bunch. My family is a mixed-up bunch, and somehow, I think Daddy and Mama and I were not unlike the Genizaros that night at the Pueblo village. We were In-Betweens.

The next day, the day of the funeral, the blanket-wrapped body was carried from the adobe house along the dirt street and up a hill to the gravesite. We walked behind. I was wearing a brown mini-dress and a pair of lizard pumps—I remember it clearly. And just as clearly, I remember the woman walking next to me from the pueblo leaned into me as we passed the church, a Catholic church in the center of the village. “We threw the priest out,” she said to me. “Wow,” I thought. “Good for you.” Even then in my lizard pumps and mini-dress, I had the seed of rebellion in my blood. Ahead of us walking just behind the body, however, were religious leaders of three kinds. A Native religious leader, a Catholic priest and a Baptist preacher. They were representative of the changes the family had gone through over generations. When we got to the gravesite, they all had their moment. But at the last and to my satisfaction, the Native holy man had the last word. Then, sans coffin, the blanket-wrapped body was lowered into the ground.

I was 14, maybe 15. I could have recited Beatles lyrics more accurately than described these unfamiliar funeral ceremonies. But parts of it are baked in my mind. The blanket-wrapped body, the peaches and blackberries, my lizard pumps and the woman I didn’t know who informed me that her people had thrown out the priest.

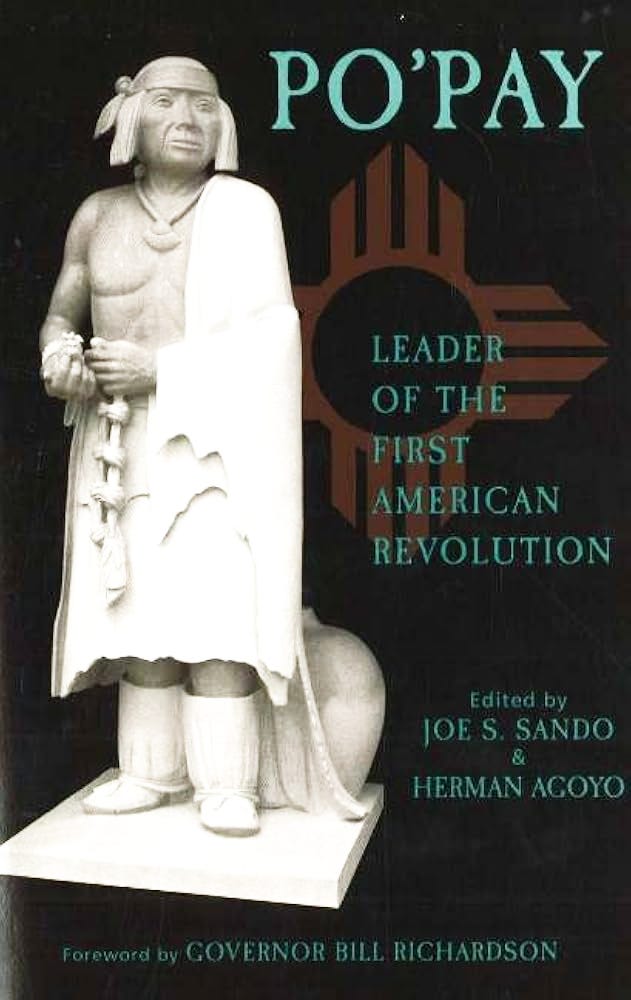

It wasn’t until decades later I learned about the Pueblo Revolt of 1680. That’s when Spaniards and the Catholic Church were “thrown out” of the pueblos of New Mexico. It lasted 12 years, and it was the only successful attempt to overthrow the occupation of Spain in the Southwest. It was accomplished through an alliance formed by a great military tactician named Po’pay. The Pueblo Revolt was a serious setback for Spain and the Catholic Church. It unleashed nothing short of terror among the clergy, and it was believed that it required no less evil a presence than the Devil himself to ally with the Pueblos to succeed in the overthrow.

The funeral procession I’d been a part of happened almost 300 years after the Pueblo Revolt. But it was worth telling in the mind of the woman whose home was the Pueblo village. That’s what she meant when she told me, “We threw the priest out.”

Memory is passed down through the generations. Like trauma is passed down. Like pride is passed down. Like feelings of belonging or not belonging are passed down. We do belong to our past. The trick is to let the belonging manifest in ourselves now, today. Let the belonging take root in our minds—it has always been present in our being.

Memories are baked into adobe walls, symbols are carved into stone. Memories of my ancestors are carved into me, too. The sacred Choctaw diamondback rattlesnake that protects the Courthouse Squirrels no doubt still protects me, too.

So enjoyed this Lucinda. Not sure if we originally bonded so well due to our Native American heritage but I expect, somehow, even if unknown at the time, it was true. I recall my grandmother who was part Cherokee and part Choctaw mentioning feeling like an “in-between”. I thought she was referring g to the unusual combination of the two tribes, but it may have been more.

I thought of it often when I would taken on a role in theatre because, in a sense, we are in-between world in that process. So great to get this backstory about the symbols for those who don’t know them and gracious to share that personal funeral story.

An amazing insight into many cultural strands. First, your immediate memories of what feeling like a Genizaro. Then to see, to recognize that many cultures do not make room for the Genizaros among them (ah, the heavy influence of the Catholic Church!), and finally to come to terms with my own feelings of "otherness". Many, many thanks.