The squirrel population in Dixon was sparse, just a few families of bushy-tails that lived in the few trees that grew on the grounds of the Beal County Courthouse. There was not a child in Dixon who didn’t love to go see the squirrels. Watch them display their agility as they tore up and down the old elm trees. Admire their boldness taking a peanut from a small, outstretched hand. Adore their furry countenances as they sat on their haunches, tiny jaws working furiously.

The exalted little rodents owned the courthouse grounds.

The courthouse was three stories of brick and concrete built in 1930. It was built in the Pueblo Deco style, a rarely-seen riff on Art Deco that employed motifs from Pueblo and Navajo cultures. The courthouse squirrels performed rodent rituals in the shadow of a building that bore witness to the past and kept its secrets.

Most everyone coming and going—doing necessary, often tedious, business at the courthouse—rarely noticed that they were watched over by the stone Thunderbird they passed beneath as they walked through doors that were decorated with images symbolizing the precious resources, corn and rain. Children playing on the grounds most likely didn’t notice the stylized faces in cast-stone relief that stared down from the upper corners of each long, recessed window in silent vigil, protecting the children’s futures. As the sun warmed the three stories of brick and stone all year long, the symbols of the sun and its rays, the symbols of the four directions and seasons, that were etched on the building quite surely went unnoticed by most. But the images of the great Thunderbird that reigned in relief above all the entrances on all sides of the courthouse kept everything that must stay in balance, in balance—living things that must remain connected, connected. The courthouse squirrels knew. Every squirrel bent a knee to the Thunderbird in gratitude. The courthouse was a fitting location for the Squirrel Empire.

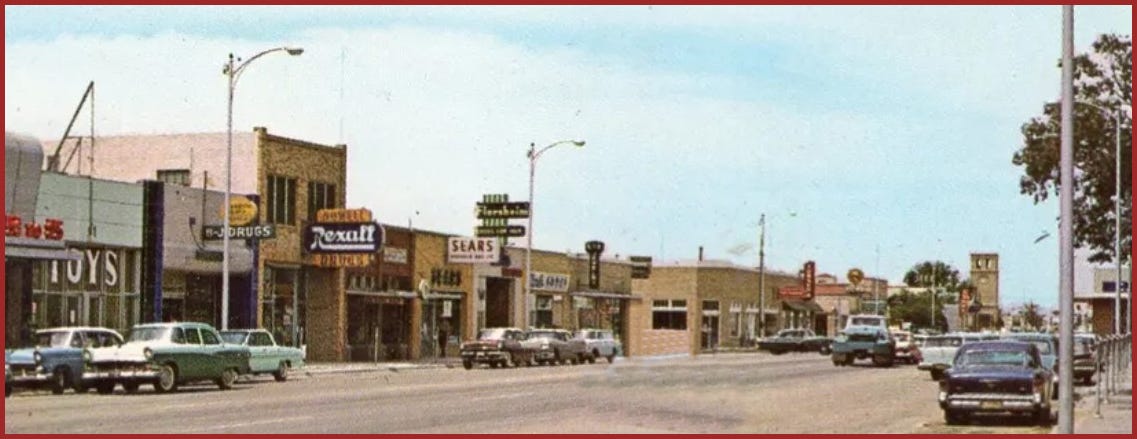

The building sat at the very center of town, facing Main Street to the West, Jefferson to the North, Central to the South and Chaparral to the East. The businesses on those streets stayed busy all the time. On the northeast corner was Powell Drug. A few doors down was the boot shop with the taxidermied two-headed calf displayed in the front window. On another corner was Beal County Bank and Trust, and catty-corner was the Beal Theatre, the only movie theatre in town. The green-and-white neon marquee popped against the deep red brick facade. Two doors down was Izzy Kramer’s dry goods store. Across the street were law offices and abstract offices. To the north was the hardware store that took up nearly half the block, and on the opposite corner was Ida’s Variety Store, a major source of treats for the courthouse squirrels.

Ida Willoughby’s corner dime store had a candy counter that rivaled the best candy counters in a hundred miles. Ida’s inventory included a little of bit of anything you might need whether you knew it or not and everything she could imagine that would appeal to kids. Ida kept a big bowl of penny candy just inside the door with a handwritten sign that read, “Kids, take one piece, just one, and remember to be good and kind every day.” Kids from teetering tots to teenagers paused at the door, peering at the kaleidoscope of candy, choosing between silver-wrapped Hershey kisses, cello-wrapped root beer barrels, dark yellow butterscotch discs, red-and-white peppermint pinwheels, sleeves of brightly assorted Sixlets, fruity Starbursts—the colors muted by waxed paper wrapping—crispy black-and-white striped peanut butter bars, Bit-O-Honeys, Dubble Bubble bubblegum, miniature boxes of Red Hots and every flavor of Jolly Ranchers—fiery cinnamon, green apple, blue raspberry.

Ida Willoughby, a widow woman, had owned the store for years. Her husband—she referred to him always as Mr. Willoughby—died of a heat stroke out on a hard, dry piece of land south of town they had homesteaded after leaving Oklahoma. He left her with four boys to raise alone, which she managed to do by taking in laundry and occasional boarders. She delivered eggs. She cooked and cleaned for old Mr. Ollie Andrews after his wife Birdy died. And late into the night after her boys were asleep, she’d sit at her kitchen table banging away on a secondhand Smith Corona, typing cotton-loan forms she was paid for by the piece. Ida was industrious—had to be to raise her boys.

Old Mr. Ollie Andrews had originally opened the little dime store on Main Street shortly after Dixon was founded and ran it with Birdy. Not long after Birdy died, Ollie decided to retire. Late one afternoon, he walked in the back door of his house just as Ida was taking a loaf of bread out of the oven. He asked Ida to sit down. There was something he wanted to talk to her about. She had been so good to him, he said as he spread a piece of warm bread with butter, and he’d grown awfully fond of her and her boys, and he wanted to offer her a loan to buy the store.

Ida said yes and no. Yes to the store. No to the loan. She’d been putting away money for years, waiting for an opportunity. And here it was. She hung out a new sign on Dixon Five and Dime and called it Ida’s Variety Store. With the help of her sons who worked after school and weekends, Ida not only made a go of the business, the store and Ida became Dixon institutions.

The courthouse squirrels especially favored Ida’s. From time to time, squirrels would go streaking across Main Street to stare in the window, straining on hind legs to glimpse the contents of Ida’s bowl of free candy. Then—before losing their nerve—dart inside—little squirrel hands reaching inside the bowl to get a sweet—then fleeing back home to safety. A driver on Main Street wouldn’t dare to run over one of the squirrels. The sound of screeching brakes and crunching rear fenders was not uncommon as people stopped short to avoid the little mavericks.

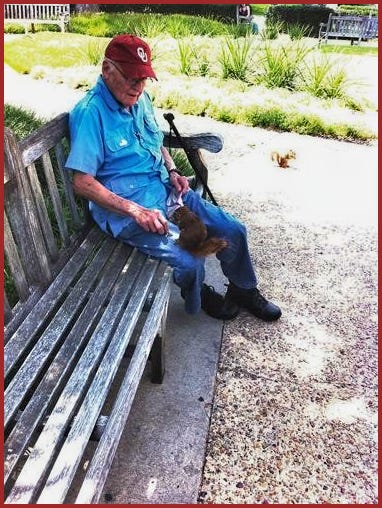

It was early October, the 3rd. Ike Gibson and little Priscilla were sitting on a bench under a big elm tree on the courthouse square. The sun was strong, but the shade of the tree and a breeze combined to make the temperature just right. Priscilla took the last swig of her Coke and a half-eaten package of Tom’s Cheese Crisps out of her pocket. Cheese Crisps were one of her favorite snacks. She liked the package as much as the treat. Liked the way the bright orange crackers were sandwiched together with peanut butter and stacked four sandwiches high in a tight cellophane wrapper. She could eat a couple, save a couple for later or for squirrel snacks. She began to break the treats into squirrel-sized bites and offer them up in her open hand. Orange crumbs outlined her feet and left the tops of her black-and-white saddle oxfords decorated in Cheese Crisp confetti.

“Daddy, look at him take it out of my hand,” she said. Ike grinned and said, “Back in Oklahoma, we’d have had him for supper, Sugar Woog.” Nothing her Daddy told her ever made Priscilla uncomfortable, not even that the cute squirrel sitting there in front of her, shaking its tail and chomping away at bites of Cheese Crisps, would have made a meal for Ike when he was growing up in Oklahoma. “How did you fix ‘em? What did they taste like?” Ike glanced sideways at his little girl and said, “Well, Nubbin, back in the Depression, my cousin Winnie Belle once made 21 quarts of dumplin’s with one squirrel.” He squinted an eye and held up one finger. “Really, Daddy?” “That’s all we had to eat,” he said, “and we were glad to get it. You better go throw away that wrapper.” Priscilla took the cellophane wrapper up to the trash can at the front of the building and balanced on the scuffed tiptoes of her black-and-white “saddle ox” to reach the trapdoor of the trashcan and push the wrapper through.

Hidden under her shoe was a diamond shape deeply incised in the concrete. A curvy line serpentined next to it. If you happened to look closely, tucked away in corners in the concrete, near the foundation, on sidewalks and steps, those two cryptic images—diamond and serpent—appeared over and over on the outside of the courthouse. Inside the courthouse, on the fifth step of the terrazzo stairs, just below the marble wainscoting, was a perfectly incised redbud blossom.

It was at the big double doors that led into the building that Priscilla’s eyes landed on a hole near the bottom of one of the doors. Priscilla glanced back at Ike. At least half a dozen squirrels had flocked around him since she left the bench. She climbed the granite steps to get a closer look at the hole. It was pretty deep and about as big around as her finger. She stuck her finger into the hole up to her first knuckle. Then she saw a similarly sized hole in the granite wall beside the doors, and then another. As she sidled up to the wall, she could feel the heat of the sun radiating off the granite as she stuck her finger into each of the holes.

By the time she got back to Ike, another half dozen or so squirrels had gathered around his feet. Priscilla wondered why the squirrels seemed especially drawn to Ike. “Daddy, did you ever see those holes up there on the door and the wall?” “Mmm-hmm,” he murmured. “Sure have.” “Well, what caused them?” she asked. Ike considered for a minute, then said, “Baby, the man who made those holes had a child he loved as much as I love you.”

John Little was part of a crew of men—highly skilled laborers—who came from Oklahoma in 1930. They worked for an outfit out of Tulsa that had been contracted to build the courthouse. It was good-paying work when many other men stood in breadlines and set up house in tent cities all over the country. John Little left his wife and three children back home while he worked in Dixon. He missed them all, but the youngest, his little girl, he missed her the most. He called her Redbud because she was born in the spring when the redbud trees in Oklahoma were in their glory. The Oklahoma hills turned pink with blooming redbuds, white with flowering dogwoods, and the squirrels rejoiced in the season.

Some of the men who came to build the courthouse camped outside of town, some stayed at Pearl’s Boarding House, but John Little got acquainted with Ida Willougby and rented a room from her while he was in Dixon. Turns out she and John were raised not far from each other back in Oklahoma, and her husband, Mr. Willoughby, had been a good friend and Lodge brother of John’s father.

John Little made friends everywhere he went. He was just like that. And friends he made on that job far away from the family he missed were a handful of Choctaw Indian men. John had smoothed over several marks he’d found in fresh-poured concrete around the job site, and one day, he happened upon one of the Indian guys making the pair of marks. John asked him, “Say, Red John.” Everybody had a nickname. “What’s that you’re doing?” Red John answered him, saying, “Little J, we want to leave our Choctaw mark here, too. Along with this other Indian stuff. You see, the diamondback rattlesnake…”

And he went on to tell John Little about the significance of the diamondback to the Choctaw people—the supernatural snake that guarded and protected their crop fields with its venomous bite but always gave warning. The diamondback was revered. Red John Folsum pushed a chaw of tobacco in his cheek and rattled a couple of dried mimosa beans. Little J jumped sideways. Red John grinned, and his eyes crinkled around the sides, knowing John didn’t like snakes, even the supernatural one the Choctaws revered.

When the job was finished and the courthouse stood proud in the center of town, John Little, who’d made a lot of friends there in Dixon, sent for his wife, two boys and his little daughter, Redbud, and made a home there on the High Plains.

While Dixon grew in the late ’20s and ’30s, Prohibition made fertile ground for crime and corruption there as it did all across the country. In fact, opportunities may have been multiplied there on the Llano Estacado, the Sea of Grass where the miles and unnoticed miles that stretched out to the horizon proved to be fortuitous for men like Ben Gibbs, who built a sprawling syndicate of corrupt operatives and hangers-on.

Born Lindsey Charles Howard, he sprung from the womb rotten. And it was a double shame, too, because his mother and father were good people. Not so their middle child who showed signs of rottenness almost as soon as he could walk. He was cruel to other children and animals, he was a firebug—burned down his father’s barn when he was six—and by the time he’d turned 13, he was sent off to reform school for trespassing and multiple burglaries. He escaped and never saw his parents again. Lindsey Charles Howard left his name behind and left criminal footprints for miles across Texas and New Mexico. He began calling himself Ben Gibbs, thought it had a ring to it. He was cunning. He could be charming. He was ruthless, and he was mean. But he managed to evade the law—police, sheriffs, even the Texas Rangers.

He rustled cattle, sold them back to their original owners. He swindled ranchland from an upright man, then wooed the man’s unsuspecting daughter. He used the ranch to further his enterprises—bootleg alcohol, illegal card games, bloody cockfights where liquor-fueled arguments resulted in guns being brandished and fired. Men died, women mourned, children became orphans all because of Ben Gibbs.

He was feared in many circles and perversely admired in others. But eventually Ben Gibbs sinned away his day of outlaw grace when he took a young girl across the state line, terrorized her and strangled her to death.

Yvonne Little, John Little’s precious Redbud, was just fifteen years old when Ben Gibbs saw her sitting in the back of her daddy’s pickup parked in front of the movie theatre. She was the prettiest little thing. Brown-eyed. The kind of brown eyes with flecks of gold in the irises like mica. And when she talked about all she wanted to do when she got grown, those flecks sparked like flint.

She loved to go to the picture show. The first movie she ever saw—when she was real little and had begged her brothers to let her go with them—was “King Kong.” She like to have never gotten over it. Probably her favorite, though, was “It Happened One Night.” The free-for-all adventures of an independent-minded young woman traipsing across the country and falling in love with the likes of Clark Gable matched her dreams. She wanted to see things, go places, be grown up and fall in love with Clark Gable. She wanted all that. Someday.

In the fall of the year, her daddy John Little sold mountain apples around the Dixon area, and once in a while, Yvonne tagged along. John knew everybody. Everybody knew him. His customers ran the gamut of prairie society.

One loyal customer was Rita Witt, who operated a bordello near the Texas-New Mexico line. John had a large order for Rita she had arranged to pick up at the Beal Arms, a hotel a few doors down from the theatre. John unloaded the boxes of fruit and instructed Yvonne to wait there, then added the admonition that she was not to speak to anyone or so much as get down from the bed of his pickup. “I’ll be back real fast, Redbud,” he said, “and we’ll go get you that pair of shoes you’ve been wanting before we head on home.” Then he picked up a crate of apples and disappeared around the side of the hotel.

Ben Gibbs strode out the front door of the Beal Arms and saw the pretty little girl swinging her legs off the side of her daddy’s pickup. He walked past her, then stopped. He rolled a cigarette, took a drag and blew smoke into the air before turning back. “Hey, girl,” he said as he approached her, “How’d you like to go to the picture show with me?” Before the night was over, Yvonne was lying beside a scrub oak tree on the sandy ground that was part of Ben Gibbs’ ill-gotten ranch. It never occurred to Ben Gibbs, as his hands tightened around Yvonne Little’s neck, that his luck was evaporating along with her life. He left her lying alone in the moonlight. Her eyes were open, catching the moonlight, but the gold flecks were gone.

A jury sat in the Beal County Courthouse, where the squirrels lived, and convicted Ben Gibbs of the kidnapping. As to the murder, Ben Gibbs sat for two months in the Beal County jail awaiting extradition across the state line.

On the day Ben Gibbs was to be transported, John Little leaned against the brick-and-concrete wall outside the Beal County Courthouse. Waiting for the sheriff and his deputy, Milo Dewalt, who had been on Gibbs’ payroll for years, to escort Gibbs to the squad car parked on Main Street.

The double doors opened. Ben Gibbs and the two lawmen lowered their heads and squinted to avoid the bright sunlight that struck them square in the eyes. Just then, John Little opened fire. The bullets missed Ben Gibbs entirely but hit Milo Dewalt in the chest. He was dead when he landed on the granite step. Another bullet grazed the sheriff. He drew his gun and aimed. He shot John Little dead on the courthouse lawn. Later on, the sheriff said, “I wisht it’d been Gibbs I killed—sorry son of a bitch needed killing more than any man I’ve ever known.”

The bullets fired by Yvonne Little’s grief-stricken father left holes in the courthouse that stayed there forever.

Many squirrel generations passed. Some things changed in Dixon. A lot of things stayed the same. One thing that did not change was the passing down of stories and history from one generation to the next. Every form of life does it. It’s how species of plants and animals adapt and morph, thrive or die out. Ike Gibson passed the stories of his life, his early years in Oklahoma, his adulthood in his beloved adopted hometown of Dixon to Priscilla, just as the courthouse squirrels passed down rodent family lore.

And one of the things that lived in the squirrel genetic memory was of the time, squirrel eons ago, when their many-times great-grandparents had hopped a ride from Oklahoma on a truck carrying men, highly skilled laborers on their way to a small town on the High Plains to construct a building. A building made in the Pueblo Deco style with ancient Pueblo and Navajo motifs. With surreptitiously carved diamonds and serpents. With a redbud blossom carved on the terrazzo stairs. On the fifth step. John Little’s Redbud had been five years old on the day he carved the flower.

The courthouse squirrels were little Okies. They felt a kinship and affinity to their human counterparts. That’s why they risked running across Main Street to peer in at Ida Willoughby and why they gravitated to Ike Gibson when he sat with his daughter on the courthouse square.

It was the 3rd day of October. Five decades later. Priscilla Gibson sat alone on the favorite bench she had shared with Ike since she was little. The sun shone, and the wind was tamed to a gentle breeze. The big elm that spread its branches to make a welcome shade had begun to turn loose of its leaves, and they floated to earth, forming a blanket around the bench where more than the usual number of courthouse squirrels were gathered at her feet. It did not stretch imagination to believe they were paying their respects to Ike Gibson, knowing that as Priscilla kissed his head and whispered, “I love you, Daddy,” he had taken his last breath that very morning.

The Thunderbird felt her need. From his stonecast perch, he became flesh and bone. He spread his immense wings, covered in many-colored feathers, and allowed air currents to carry him aloft, between the sun and his fortress. He cast his protective shadow over Priscilla Gibson as she was walking away.

Priscilla would get on with her life, but first she had to get her grieving done. She got in Ike’s red Ford pickup—Ol’ Red belonged to her now. She turned the key. Only two people had ever driven Ol’ Red. Priscilla pulled out onto Main Street, slow like Ike would have done.

Share this post