It was 12:15 in the afternoon. Carla Spears was serpentining her way past tables and booths in the Ranch House Cafe. A line of small brown plastic wood-grain bowls filled to the top with iceberg lettuce and diced tomatoes and drenched with creamy Thousand Island dressing ran up the length of her left arm. As she swept past tables, her right hand, seeming to operate completely independently of her left, placed a bowl in front of each hungry customer. On her next pass, she handed out glasses of iced tea in tall red plastic-textured tumblers and refilled cups of coffee while simultaneously tossing cellophane-wrapped packets of Saltine crackers with a deftness, grace and precision that attested to her past glory as a champion majorette and high school baton twirler in Antlers, Oklahoma.

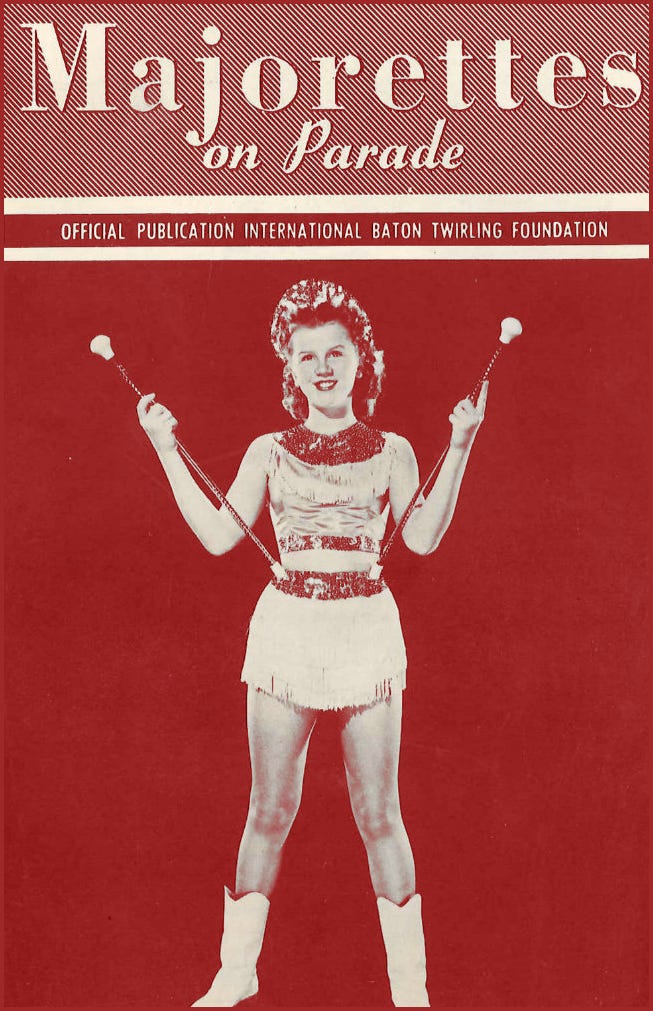

In 1959, Carla had twirled her way through Oklahoma and all of Tornado Alley like a Category 5 cyclone, winning every competition the National Baton Twirling Association put on. She wound up one of 124 finalists out of some 30,000 that had competed nationwide to go to the Winter Carnival in Minnesota, where ultimately the two top finalists battled it out in front of a national TV audience on “I’ve Got a Secret” hosted by Garry Moore. Tragically, in the semifinals, by one slip of the wrist, she lost to Imogene Conway of Dubuque, Iowa and was robbed of her one chance to go on television. She never got over it. She had at least graced the cover of Majorettes on Parade magazine, and that was some consolation, but it had been the biggest regret of her lifetime—up to now.

She had recently gotten divorced from her high school sweetheart, the star quarterback of the Pride of Antlers, Oklahoma football team. It was an imprudent marriage and doomed to a failure that came to fruition when her young husband, Dub Spears blew his big chance to play pro football when he and some of his buddies went on a drunken spree, stole a Pontiac Bonneville and joy-rode across half of Oklahoma. Dub Spears was sentenced to time served but was nevertheless a convicted felon who turned into a mean alcoholic and abusive husband. By sheer will and determination, Carla escaped a stereotypical scenario. Late on the night of the day she’d gone to the bank and cleaned out what little was in their joint bank account, Carla took off in a Chevy Impala she’d bought at the local used car lot and parked at the end of the block. With little more than the clothes on her back, her prized majorette outfit and about 20 dollars, she headed south with no idea of a destination.

She wound up at 5 a.m. in the small town of Dixon, sitting in the car in front of the Ranch House Cafe. The breakfast shift was about to start. She went in for a cup of coffee. The waitress for the breakfast shift had called in sick that morning, and Carla wound up with a job that would prove to be a lifesaver for many reasons.

Cafe regulars were as appreciative of Carla’s charm as they were for the plates of delicious food she delivered to their tables, most of them piled high with chicken-fried steaks smothered in cream gravy, accompanied by French-fried or mashed potatoes, green beans and tall hot rolls with the intoxicating aroma of yeast and the heat of the oven Tot Hecheverria had just pulled them from. Consensus was Tot’s chicken fries were the best in town, but his enchilada plate came a close second, with red sauce and cheese blanketing rolled tortillas that were filled with a closely guarded secret ground-beef recipe that Tot shared with no one, adhering to the principle that a secret between two people is secret only if one of them is dead.

A meal at the Ranch House was not complete without pie. Tot’s pies were crafted by a master. Especially prized were the peach and pecan pies he made from the plentiful fruit and nuts he harvested from his own trees. His peaches were from seeds from his daddy’s trees and the pecans came from the little trees that came up “volunteer” among the peach trees. Summertime, it was peach pie, and by the time football season was in full swing, there were sure to be dark, rich, sweet slices of pecan pie on customers’ plates.

The Ranch House Cafe was the Roman Forum of the town, and Tot Hecheverria presided over it with the benevolence of Augustus Caesar. Like the emperor, his own family tree had its share of royalty and rogues. Tot could trace his lineage back to Europe, particularly the Basque country that straddled Spain and France. He counted among his ancestors adventurers and artists, soldiers and conquerors, fortune hunters and felons—and even a Queen of England, Berengaria of Navarre, wife of England’s Richard the Lionheart. But it was his reputed ancestor from southern Spain who struck his fancy the most. Miguel de Cervantes.

Tot kept a print of Picasso’s drawing of Cervantes’ hero Don Quixote framed above the cash register alongside two photographs of windmills. One was of the formidable white giants on the plains of Castilla-La Mancha, Spain; the other a picture of a puny—by comparison—windmill like the ones that dotted the high windswept and storied plains of the Llano Estacado right where the small town of Dixon was perched. Tot liked to say that Cervantes’ Knight Errant would have fared better had he done his jousting around here. That was only one of the many references Tot made to the chivalrous caballero, his roly-poly sidekick and his beautiful lady, Dulcinea.

Tot had been to New York City just once in his life. He had closed the Ranch House Cafe for a full week this past fall and attended the opening night performance of “Man of La Mancha” on Broadway. Just a few months later, on a cold Sunday night, the packed tables at the Ranch House fell silent when Tot turned up the volume on the TV as Ed Sullivan introduced Richard Kiley, who recreated his showstopping rendition of “The Impossible Dream.” Tears streamed down Tot’s cheeks as he listened. The rapture on his face attested to the emotion he attached to every word, every syllable, every soaring note. Tot’s quiet strength fully made up for any possible perception of weakness such a show of emotion might suggest. Tot Hecheverria was a rock. But his strength had not been forged lightly. His kindness existed in spite of cruelty that had been visited upon him by people who should have shown only love but didn’t.

Antonne Xavier “Tot” Hecheverria’s birth was attended by Estrella Arreola. Estrella and her husband Fermin had lived on the vast Hecheverria ranch outside of Dixon and worked for the family for years. The births of her own seven children gave Estrella the experience she needed to guide Gabrielle Beaulieu Hecheverria through her first labor. On a night punctuated by claps of thunder and bursts of lightning so close electricity coursed through her bones, the young Frenchwoman delivered a strong son to her husband Mattin.

An hour later, Estrella, wiped tears from her face and whispered to the new father, “Lo siento, ella murio.”

Before she died, Gabrielle held him, held her baby boy. Her eyes took him into her soul. His tiny face began to dim. She spoke a name. Antonne Xavier. Bright, priceless one. And so the baby was named. Mattin Hecheverria never forgave this son for the death of his mother, Mattin’s beloved wife Gabrielle.

Mattin had two children with a second wife, Floria. Floria, who came from New Orleans to marry the landed and wealthy Mattin, also bore the brunt of his grief. She also died young. Her death was of loneliness and neglect. Mattin remained embittered and unreachable his whole life, and from the grave he landed the coup de grace when, at the reading of his will, Antonne Xavier “Tot” Hecheverria learned he’d been totally disinherited. At Mattin Hecheverria’s graveside, his first-born son Tot, who’d never stopped revering and loving his remote and bitter father, sang the beautiful lyrics of a Basque hymn. “Blessed is the Guernica Tree loved by all Euskaldunes. Give and spread your fruit throughout the world. We adore you, Sacred Tree.” His half-siblings took full possession of their father’s sheep ranch, for which they had neither interest or emotional investment.

Estrella and Fermin Arreola lived in a small house next to the grand one Mattin had built for his beloved bride Gabrielle. For decades, they ran the Hecheverria ranch operation and carried on Mattin’s centuries-old traditions of Basque sheep ranching. Yellow school buses brought generations of schoolchildren on field trips to watch the ranch hands shear sheep and later enjoy cool glasses of Basque cider Estrella served from huge crocks.

About 2:00, when the lunch rush had slowed down, Carla Spears cleaned out the cash register and got the daily deposit ready to take to the bank for Tot. He’d added bookkeeper to her duties She was real good at it—even started doing books for some of the small businesses around town. With the extra money added to tips she made from the lunch shift at the Ranch House Cafe, she managed to save enough money in just four years to put a down payment on a little one-bedroom one-bath house in a nice part of town. She was frugal. She stretched every dollar, making it count for something. Carla and Becky Fairweather had become close friends, and Becky kept Carla outfitted in stylish clothes she put back for her from the sales rack at The Style Shop. They shared one extravagance—they went to the monthly Roadrunner Country Club dances, a dress-up affair they looked forward to. The Roadrunner Club was a members-only outfit, and neither of them could have afforded to join if it weren’t for Tot, who paid their annual dues. “You girls need to splurge ever’ once in a while,” he said one Christmas Eve as he handed them each an envelope with Roadrunner Club cards inside.

Becky Fairweather and her little boy Skippy, Carla Spears and easily two dozen more of Tot’s current and former employees and their families were always invited to spend Christmas Eve at the Ranch House Cafe. He closed the Cafe at 5 p.m. sharp on Christmas Eve and, with the help of Chuy, his longtime employee, put on the finest Christmas Eve anyone could want. Chuy ducked out mid-party to don a Santa suit and hand out presents. The kids recognized his crooked gait, but not one child ever let on.

Tot put on a spread—roast turkey with cornbread dressing, mashed potatoes, yams in buttery brown sugar, dozens of tamales, giant pots of pinto beans. And the pies—pumpkin, pecan, chocolate. There was always a German chocolate layer cake and the obligatory fruitcakes sent to the Ranch House from well-meaning customers, most of which went untouched and were stored in the back of the freezer to be brought out again the next year.

Tot hadn’t spent a Christmas at the ranch with his own family for many years. The Ranch House family was the one he cherished, nurtured, and it was there that Tot Hecheverria was loved in return.

Chuy Aguirre had worked at the Ranch House Cafe for 15 years and, although his official job was dishwasher, his true occupation was loyal righthand man to Tot. It was almost too coincidental that Chuy was short and rotund and, just like Sancho Panza, he would have followed his own Don Quixote—the tall, wiry Tot—to Hell and back.

Chuy and Tot had grown up together on the ranch. They’d been almost inseparable since first grade when they took their first school bus ride to town and shyly started their first day of school in Miss Benson’s class.

Jesus “Chuy” Aguirre was the only son of Jaime and Alazne Aguirre. Jaime and four other men had come from Spain especially to work for Mattin Hecheverria. They possessed all the centuries-old knowledge about Basque sheep ranching that had been passed down from father and grandfather and grandfather before, and just like Mattin it was in their blood. They couldn’t have done anything else. Within the year, Jaime sent for Alazne, the young wife he’d left waiting for him, and together they had devoted their lives to the Hecheverria ranch and the Hecheverria family. To Jaime’s great sorrow, his only son was born with a physical weakness that all the determination and will father and son together could muster would not be enough to let Chuy work sheep alongside his father and the other men.

From the time Chuy was a toddler, Jaime ignored Alazne’s protests and took his eager little son with him everywhere. Where Jaime was, so was Chuy, an appendage to his father. He absorbed every aspect of the ranch. At shearing time, his young Basque blood stirred as he watched strong men lift the animals high, tossing them on their padded sides and shearing the thick wool that came off in dirty white swaths before letting the denuded sheep trot back, bleating, to their flock of similarly naked animals.

Chuy’s ambition was to follow this same path his heritage obliged him to take, and Jaime never tried to sway him from that goal. But on Chuy’s very first day of school, the actions of cruel little boys began to make him aware of how physically weak he was compared to them. And it was on that day his friend Tot rescued him from young tormentors and became his lifelong protector.

Years passed. Summers came and went. It became more and more difficult for Chuy to accompany his father on horseback. The pace was arduous. Reluctantly, he began to stay behind, keeping the barns clean and horses fed. When Chuy was grown, with nothing to do, he left the ranch and fell into a kind of despair. It was Tot who found him. Sobered him up. Gave him hell. “Listen, Chuy, you’ve got to get ahold of yourself. I don’t have time for this nonsense. I’ve got the Ranch House to run, and I expect you to pull yourself up and help me do it.”

It was late afternoon, and Chuy had finished cleaning up after the roughnecks and cowboys who’d been in for coffee. He noticed a mud-caked pickup still parked out front. Wasn’t one he recognized. And he thought it was odd—since it wasn’t deer season—that there was a rifle and shotgun on the gunrack behind the seat. A man he didn’t recognize sat in the cab of the pickup for several minutes before coming inside and sitting at the counter. He seemed to be in another world, or maybe he was just tired. His face seemed to have more lines than his age would have earned him. He had what looked like at least a two days’ growth of beard. He smelled of whiskey and sweat and unease. It made Chuy uneasy. He picked up a fresh-brewed pot of coffee and offered the man a cup. Asked him if he wanted to see a menu. The man said, “No, but I’ll have a piece of that pie.” Chuy obliged, then went about his business, keeping his eye on the stranger.

As he wiped the front tables, Chuy glanced out the window again and noticed the pickup had Oklahoma plates. “You just passin’ through town?” Chuy asked. “Yeah,” the man said, then “Maybe stayin’.” Chuy could feel it—something wasn’t right about this man.

Chuy headed to the kitchen, gave Tot a heads-up, then went out the back door. In a minute, Tot came out the swinging kitchen door into the dining room, his apron covered in gravy and flour as usual. As he glanced through the partially opened blinds, Tot watched Chuy circle the lone pickup, looking it over for clues about this man who was “passin’ through, maybe stayin’” and why he had chosen Dixon. Tot made small talk with the man, weather mostly. Then he said there was a football game tonight at the high school, first game of the season. Tot thought the man might take the bait and confirm a suspicion that had taken root in his mind. His suspicion only deepened when the man avoided the bait.

Tot excused himself. Going back through the swinging door, he snatched up the phone on the wall in the kitchen and called the bank where Carla had gone to take the daily deposit. Closing his eyes, Tot prayed silently he’d catch Carla before she headed back to the Ranch House.

One of the bank tellers answered the phone and said Carla was still there. “We got to visitin’, but she says she’s on her way right now.” Tot said, “No. Tell her to stay there. I may need her to run another errand for me.” “Sure thing, Tot,” she said, but when she turned back to relay the message, Carla was getting in her Impala and heading back down Main Street toward the Ranch House.

The man finished his pie, slapped money on the table and disappeared out the front door. When the bell on the door jangled, Tot rushed through the swinging kitchen door and saw the man drive away. Tot ran out the back. His pickup was already moving when Chuy jumped into the cab.

They almost made it in time to save her—almost. When they got to her, the mud-caked pickup was angled across the wide street, the driver’s door still open, and Dub Spears, Carla’s ex-husband, was dead in the road. When he’d seen her coming down the street, he shot through the windshield of her Impala. Her car careened off the street into a telephone pole. Dub Spears ran down Main Street toward her. Tripping. Falling. Stumbling to his feet again. He ran to her. When he saw what he’d done, saw her beautiful, bloodied face lying against the steering wheel, he walked back to his pickup, reached on the ground and picked up the shotgun, put it in his mouth and pulled the trigger.

Carla stayed in the hospital for almost a month. Chuy kept the Ranch House going while Tot stayed round the clock at her bedside. A year later, the only outward sign that anything had happened at all was the scar above her right eyebrow. She added long bangs to cover it.

Tot agreed to let her come back to work sooner than her doctor recommended. He had a strong belief that, for her, being surrounded by friendly, familiar faces would be as healing as anything else in the world could be. Ed Turner, who ran the auto body shop, put Carla’s Impala back together. And put her heart back together. Another year passed. Another summer came. Tot walked Carla toward Ed, who stood waiting for his bride. Tot leaned into him and said, “Take care of my girl.”

Years passed. Within the Ranch House family, marriages were made, some were broken, bonds of friendship were forged, children were born, old friends were bid goodbye. At fifty, Tot Hecheverria married a woman he’d met in New York on his trip to see “Man of La Mancha.” They had exchanged letters for years. She always signed hers “Your Darling Dulcinea.” After her husband died, she came to Dixon to visit, and she never left. She and Tot eventually retired to the High Country where they built a mountain home. A Great Pyrenees dog named Cervantes guarded the property and reminded Tot of the sheepherding heritage his father Mattin—in spite of his bitterness—had instilled in his son. Tot placed the Ranch House Cafe in the capable hands of Chuy Aguirre to run.

Carla ran for County Treasurer and held the post for 25 years, becoming one of the longest-serving elected officials in the state. She appeared on television, at last, in a feature story. She talked about winning. Not winning twirling competitions. Winning elections.

When Tot Hecheverria died, the pews in the only Catholic church in town couldn’t hold all the mourners. Father Espinosa himself was overcome with emotion to see the outpouring. Music ended the service. Music Tot had loved. The soaring baritone voice of Richard Kiley singing from “Man of La Mancha.”

“To fight for the right without question or pause.” Lyrics that could have been written about Antonne Xavier Hecheverria.

Share this post