Manzanar War Relocation Center

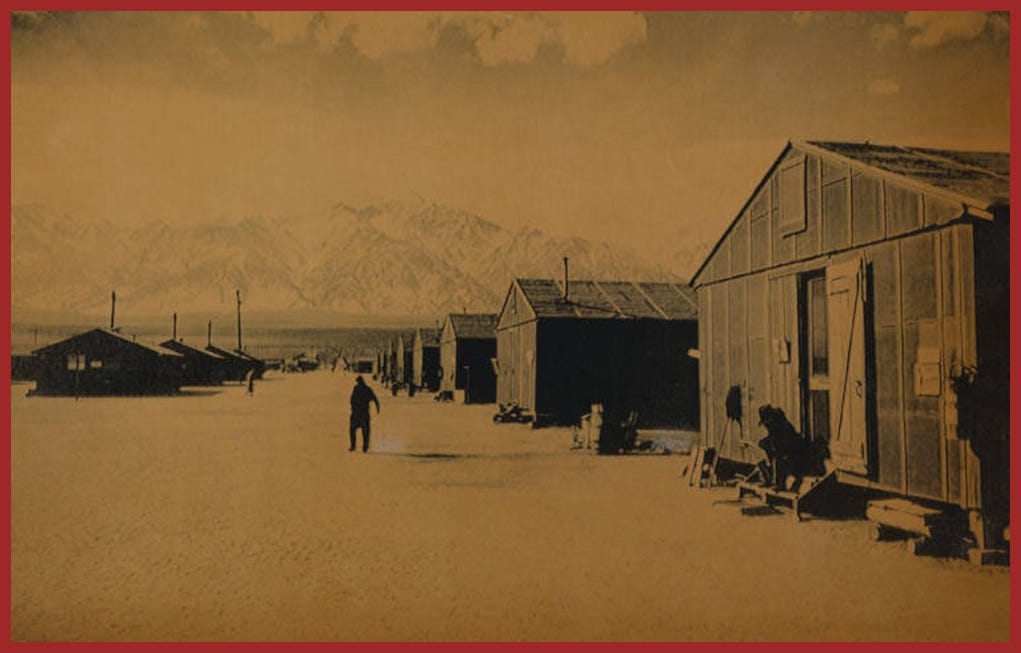

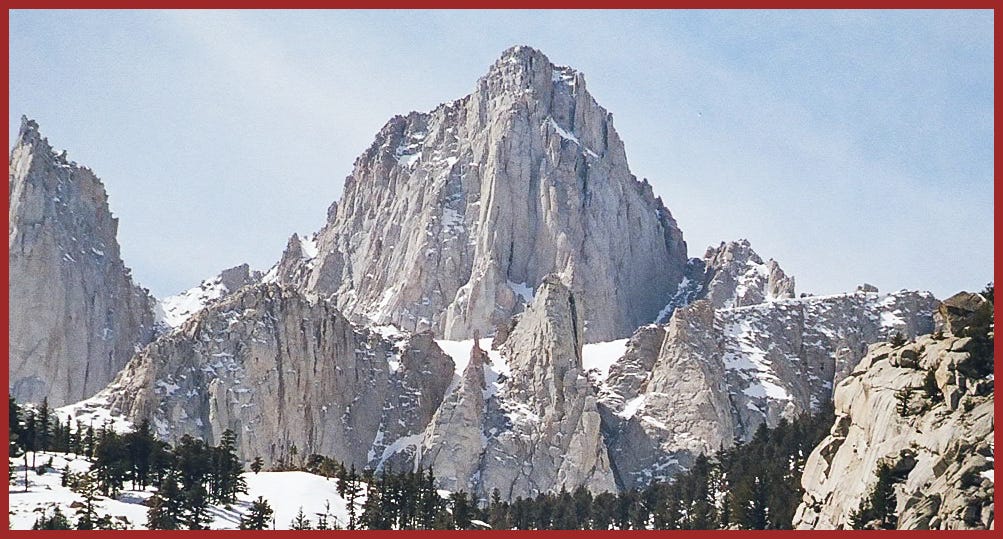

Mount Whitney in the Sierra Nevada range rises from the valley floor, the result of a 10-million-year geological effort to heave the granite colossus over 14,000 feet toward the sky. The Paiute people revered it as the place where the Great Spirit watched over the destiny of his people. Before White settlers called it Whitney, the Paiute called it Too-man-i-goo-yah, Very Old Man. Very Old Man watched. Very Old Man saw all the things that happened at his feet in the Owens Valley.

The summers baked and parched. The winters chilled and stung. Too-man-i-goo-yah watched. The ages carried the memories of what he saw. He watched as his people were displaced, killed over land they had cherished and protected. He saw Hollywood moviemakers come there to make cowboy-and-Indian pictures. He saw fertile land lost to greed. He saw water lost, watched as the precious resource that had nourished the valley was diverted to quench the thirst of the population of the City of Angels.

It was early December, another 70-degree day in Los Angeles. Mrs. Yoshida was preparing dinner, listening to the radio and talking to herself, rehearsing the lecture she was about to deliver to her son Howard when he came through the kitchen door. She knew he’d been down there at that Philippe place after school eating a French dip sandwich, spoiling his dinner with American food when he could get perfectly good food at home and not spend a dime for it. An ad for Sato’s Used Cars came on the radio, and she added another item to her agenda. She would dispel any notion her son had about spending good money on a car just to impress the girls when he could take the bus. Save up the money he was making working with his father—get a good education. All this talk about Nisei, second-generation kids. Those Watanabe twins were an especially bad influence. She’d seen that one twin wearing a Zoot suit.

Howard Yoshida waved goodbye to his buddies Tag and Mutt Watanabe and raced down Spring Street to get home. He was sure to catch hell from his mother if he was late again. Besides, he looked forward to her cooking. Mrs. Yoshida could cook up a storm.

The screen door slammed. Mr. Yoshida cleared his throat, then shook the Rafu Shimpo, letting his son know he was attached to the two legs sticking out beneath the daily Japanese newspaper. Mrs. Yoshida called out her son’s name as he was about to disappear into his bedroom. Howard stopped, took a breath and turned toward the kitchen. Mrs. Yoshida watched her son glance malevolently at the tiny, gnarled elm tree as he passed it, sitting there in its special spot. She heard him curse it under his breath. “Damn you, tree,” he taunted. “Damn you.” She knew Howard hated Worthy One, his father’s century-old tree. Knew her son was jealous of the time his father spent doting on the tree. She knew, too, that Worthy One, the little elm tree, hated him back. She heard the little elm, every time the boy passed, muttering curses back at Howard. “Damn you, boy,” he cried and shook his tiny limbs covered in serrated leaves, let go of tiny shards of gray, grizzled bark that flew the inch or so to the blanket of moss that covered the miniature plot of ground below.

The elm tree envied the boy as much as the boy envied it. Worthy One yearned to trade places with the boy, yearned to leave the constraint of the brown rectangle, longed to reach height and girth, send his roots wide and deep. After more than a century, Worthy One still yearned.

Howard’s father folded the Rafu Shimpo, placed it in a pile at the end of the sofa before joining his family at the perfectly set dinner table. When their meal was over, Mrs. Yoshida tidied up. Put each china dish in its place in her china cabinet and sunk into a chair with a cup of her special tea. Another daily victory was won. She sighed. Quoted Mel Allen, the New York Yankees announcer. “How a-bout that?”

Mrs. Yoshida’s hands and mind were always busy keeping her three children and her husband tended to. It seemed they inhabited a great nest, crowded together, mouths gaping, waiting for her, always wanting something of her. Keeping them satisfied kept her mind on life as it was, not as it could be. That and her love of baseball. The radio was her best companion, especially from April to October.

Aki’s father had been a teacher and the coach of one of Japan’s finest high school baseball teams. Aki sometimes sacrificed a cherished music lesson to steal away with her father to the field and watch the boys play ball. Her name, Aki, meant autumn or clear. When she was a child, her mother would alternately use those adjectives to describe her. Some days, she thought of her daughter as autumn—harvest done, duty done. Other days, she saw the girl as having the clearest vision of anyone she had ever known. A wise girl with purpose and a clear vision of life—as it was, not as it should be.

Aki married one of the baseball players her father coached, Hideo Yoshida. He had unrealistic dreams, Aki thought, but when California called his name, Aki gave up her music to follow her husband to America. Hideo believed he could become a famous American baseball player. But he wasn’t saikou. He was never “the best” as he’d dreamed he would be. In her heart, Aki had known he would not be. It was her duty to help him try.

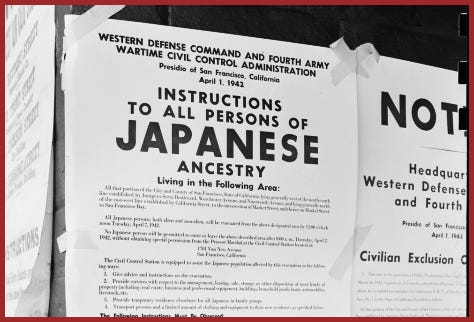

Hideo and Aki settled into the sizable Japanese population in Los Angeles. Southern California was nice. Nice house, nice kids. Hideo joined a growing group of Japanese gardeners who tended the yards of well-heeled Angelenos. He was in demand, arguably one of the best. Nothing could have prepared them for what happened next. February 19th, 1942. Executive Order 9066, signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

A great eagle had descended on the nest Aki Yoshida tended.

No trial. No hearing. No due process.

The Yoshidas had two weeks to prepare for the unthinkable. Internment. Some people had less time to decide on and gather what they could carry. Mrs. Yoshida believed the extra time made things worse. More time to prepare meant more time to agonize over what they were forced to leave.

She got to work whittling down their belongings into essentials while Hideo, nearly inert, silently raged. He tended his tiny tree while their world fell apart.

They’d been told to leave their homes empty. In a small act of defiance, Mrs. Yoshida decided to leave her china dishes behind exactly as they were, perfectly arranged in the china cabinet.

It was early morning. A knock. Soldiers. Bayonets. A truck motor running. Hurry. Hurry. A rush to dress their children, grab their belongings before they were herded toward a waiting truck.

Hideo turned to go back, was pushed ahead. He strained to see through the cloud of vapor that rose from the tailpipe in the early morning, choked on the exhaust as the truck pulled away. Worthy One was left sitting on the front step. A careless boot had cracked his brown ceramic container.

For more than a century, Worthy One had fulfilled his duty to bring pleasure to his family. What was he to do now? The little tree wept.

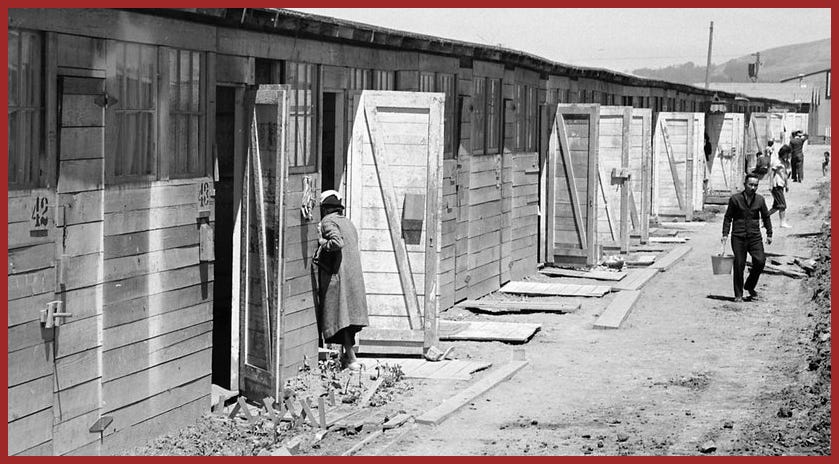

The Yoshidas’ first stop on their way to the internment camp was the Santa Anita Racetrack. Racehorses had been moved to make room for families. Hundreds of people emerged through the sickening exhaust of the trucks, lugging their belongings toward horse stalls that made hasty living quarters.

On the second night at the racetrack, Howard located his buddies, the Watanabe twins, packed into a stall several stalls down from his family. Their father was sitting on the floor in the back of the stall bent over something, mumbling. Talking to the precious seeds and seedlings he’d managed to save from his prized vegetables. After Order 9066 was issued, the Watanabes, like many Japanese families, had been forced to sell their truck farm for pennies an acre.

While exploring the storied grounds of Santa Anita Racetrack with the Watanabe brothers, Howard spotted a girl peering out of her family’s crowded stall. Her name was Betty.

Weeks passed. Before they were transported, clear-eyed Mrs. Yoshida watched her husband Hideo become an old man, watched as he retreated into the nest she tended. In those same weeks before they were transported, Mrs. Yoshida watched her son Howard become a full-grown man. Were his wing feathers strong enough? No, not strong enough to fledge, not yet, she thought. Howard was 17.

Too-man-i-goo-yah, Very Old Man, watched the Yoshida family and the terrified throngs of Japanese Americans, two-thirds of them American citizens —watched them being swept into the Owens Valley. Very Old Man had seen his own people swept away from the Valley. Destroyed.

The wind howled. Too-man-i-goo-yah wept.

The Yoshidas settled into a 20-by-25-foot section of a barracks—one of hundreds, row after row, encircled by barbed wire.

Howard and Betty married, attended by eight guard towers armed with machine guns. The government said the guards were there to protect them. It begged the question then, “Why were the guns aimed inward?”

Mrs. Yoshida took her daughter-in-law into the nest, and soon, in the Yoshidas’ cramped quarters, she helped Betty deliver a baby girl. She cleaned the baby and wrapped her granddaughter in the soft blanket Yumi Watanabe had given her —one of two matching blankets Yumi had used for her twin boys. Mrs. Yoshida could see the ground below the barracks through the wooden slats on the floor. She could smell it, the dirt. She would always associate the smell of dirt with the moment she placed her grandchild into her daughter-in-law’s arms.

Now there was one more set of eyes peering up at her from the nest. But the nest was getting tattered, its neat construction frayed.

There was no insulation in the barracks to keep out the freezing temperatures in the winter or the stifling heat in the summer. Soap and hot water were scarce. There wasn’t a decent place to wash diapers. Mrs. Yoshida spent hours a day in lines waiting, always waiting for every meager thing the government provided.

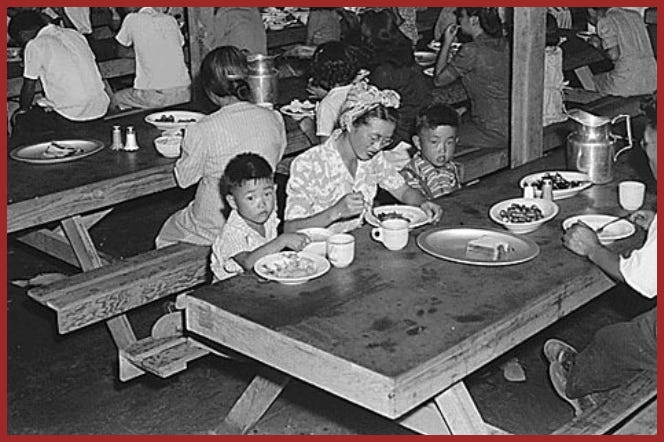

Mealtime in the camp erased family structure. Good manners and the rituals of Japanese meals died. People were served in shifts, cafeteria-style. Horrible food —wieners and canned spinach —was served on partitioned trays. Metal trays and metal cups were mean substitutes for Mrs. Yoshida’s china. Army cooks used to filling American GIs’ bellies had no idea how to prepare Japanese food. Not even how to cook rice. But they learned. And with the truckloads of hot dogs that arrived, the cooks invented a special dish—Weenie Royale, made with hot dogs, scrambled eggs and soy sauce served over rice. A plate of it was even photographed by famed photographer Dorothea Lange, who had been hired by the government to make a photographic record of camp life.

And she did. She captured a true look inside. Showed scenes created by Executive Order 9066. But some officials—higher-ups—decided her photographs displayed U.S. war policies in a bad light and impounded her photos for decades.

Mrs. Yoshida’s efforts to control her two younger children, Howard’s brother and sister, were futile. She had Betty and the baby to tend. Milk was scarce. Some women managed to get calcium tablets by mail order to sustain themselves as nursing mothers. Hideo grew more detached and, without Worthy One to dote on, he took up another pursuit. Like a lot of men, he kept pails beneath the floorboards where he brewed contraband sake.

Baseball teams were organized. Mrs. Yoshida was a standout on her softball team. Some said she was saikou. As much as she tried, she was never able to persuade Hideo to join a team.

Hideo spent many of his hours with Too-man-i-goo-yah. Very Old Man knew Worthy One.

A day came when Hideo did not return to the barracks. In the waning hours of that day, Mrs. Yoshida found him lying in the arms of Too-man-i-goo-yah. It was the first time she’d seen contentment on his face in a long time. The Yoshidas buried his body there in the sorrowful, windswept Owens Valley.

Mrs. Yoshida created as much as she could out of the little they had. She turned dull scraps she found at the camp into bright trinkets and dropped them into their nest. She wanted to remind her family of the life they had before. There was life before Manzanar War Relocation Center. She promised them they would have it again.

Howard and Betty’s baby girl was going on a year old before Mrs. Yoshida discovered there was a prison within the prison they were confined in.

It was windy. She was teaching the baby to walk, holding her grandchild by her fat little hands. The baby’s bare feet kicked along the dirt expanse between the rows of barracks. She made awkward steps—at first holding on—then brave advances hands-free before falling down hard on her padded bottom.

Mrs. Yoshida looked around and realized they’d taken a wrong turn. She’d never seen this part of the camp. A woman in a white nurse’s uniform ran out of a door. As she passed Mrs. Yoshida, she yelled at her to go back to her section. “You have no business here.” Afraid of breaking any rule, Mrs. Yoshida started to hurry away. She glanced back and saw dozens of children looking out a long row of windows. Window after window filled with children’s faces.

The woman in the uniform snatched up a toddler wandering in a fenced playground beside the building. He made no noise, but he was crying. His eyes were squeezed shut against the blowing sand, but his tears defeated his tightly closed eyes and swiped tracks down his cheeks. Rivulets of snot mixed with dirt ran from his nostrils. Mrs. Yoshida could no longer see the woman. She saw only a white uniform holding a child and wrestling with a door. The child opened his eyes. He stretched his arms out to Mrs. Yoshida and screamed, “Mommy.”

Mrs. Yoshida ran, staggering. Sand stung her legs. Wind whipped her skirt, threatening to tangle her up. Yumi Watanabe saw her and ran to her. “Who are those children back there, Yumi? I saw children.” Yumi Watanabe told her what she’d learned. Told her about the babies who lived in the Children’s Village. Little kids deemed a threat to the security of the United States of America. Yumi told her about the other prison—the prison within their prison. Orphans lived there, isolated. Some were true orphans, their parents dead. Some were separated from living parents who were being held on suspicion.

The Los Angeles Times explained it succinctly in 1942 when it printed, “A viper is nonetheless a viper wherever the egg is hatched. So a Japanese-American, born of Japanese parents—grows up to be a Japanese, not an American.” This despite internees—young men, old men, young women, old women—having signed loyalty oaths to the United States of America. Line 27 in the oath, a single sentence, required them to swear allegiance to the United States and foreswear allegiance to the Emperor of Japan. These Japanese who did not have allegiance to the Emperor of Japan found themselves, if they signed the oath, admitting a falsehood in order to demonstrate their allegiance to the United States. It was the definition of damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

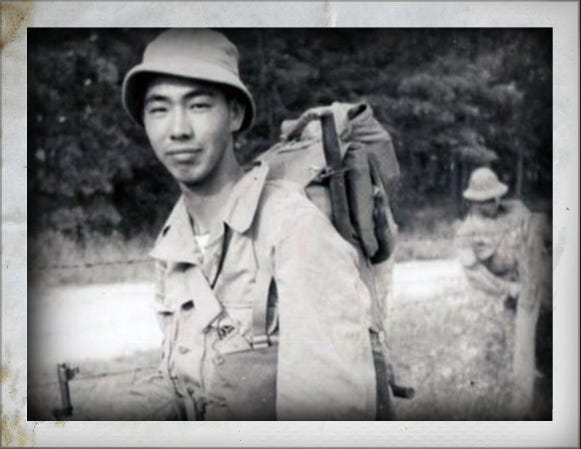

Howard and Betty were expecting their second child when, incredibly, the Army came begging. The gall of it was breathtaking. The U.S. was facing a shortage in manpower. Like many other American men, Howard boarded a ship and left his family behind.

But unlike other American GIs, Howard Yoshida’s family was living behind barbed wire when he left them.

Share this post