Read or listen to "Tot Hecheverria and The Ranch House Cafe” here.

Didn't we all love field trips when we were schoolkids? I especially remember two field trips. One was to the farm of one of the boys in our class. I had never seen his mother before, but when we arrived, she welcomed us. She was fabulous! She was wearing a cotton print dress—very practical and nothing like the fashion-forward dresses my mother wore. Everything about her attire was practical. The apron that covered the front of her floral print dress had big pockets and was starched and ironed like the dress. Her hair was sensible, too. And of course, her shoes were sturdy—not stylish but not unattractive. Those shoes would take her anywhere, I figured. She was standing in front of a sensible house way out in the country without a single other house in sight. That was amazing to me and a little bit terrifying.

And she had treats for us. Something to drink and cookies, probably. But what I remember—what I will never, ever forget—are the oranges. She had an orange for every kid and boxes of soft peppermint sticks—the porous kind that are about four inches long. She instructed us to impale our orange on the peppermint stick, then suck on the stick as hard as we could until the juice began to flow through the sweet candy. What eventually filled our mouths was a flavor I'd never had and will never forget. Tangy citrus sweetened by sugary peppermint. Wherever did she come up with that idea? Mama would never have thought of such a thing. The woman will remain in my memory forever, the practical, sensible-looking woman with the magic orange treats.

The other field trip that has stuck in my memory was to a sheep ranch. I didn't know there were sheep ranches—all I ever saw on the flat landscape where I grew up were cows and horses. I always assumed a ranch was, by definition, a cattle ranch, not a sheep ranch. But that’s where we were going, and in preparation for the field trip our teacher told us about the Basque people—and the Basque people and culture caught my imagination my entire life. It’s worthy of imagination, too, because the culture is rich and old and storied. It's why I created Tot Hecheverria and gave him a Basque heritage—with a whimsical fondness for a Spanish hero who jousted at windmills, loved a beautiful girl and dreamed about the impossibility of always being true and good.

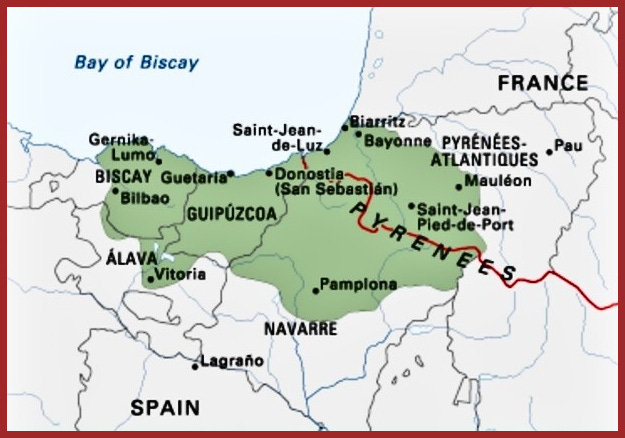

The Basque homeland is a small region tucked between France and Spain near the Pyrenees mountains. Basques are neither French or Spanish—they’re a separate people with a unique culture and a cherished ancient language, Euskara. It’s the oldest language in Europe, and it’s unrelated to any European language. Its origins are a mystery.

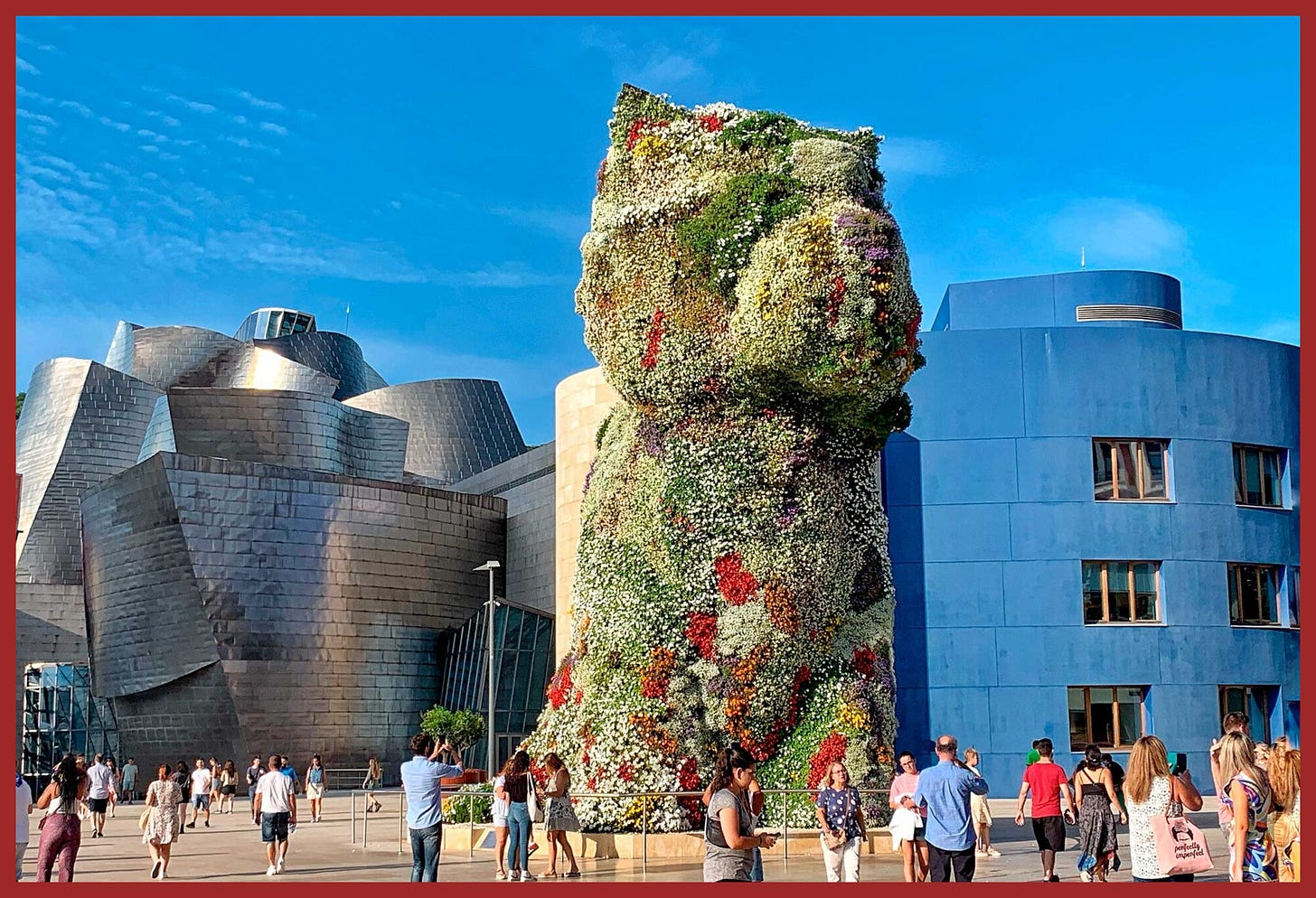

Today, the Basque region is a cultural powerhouse. It’s home to Jeff Koons' "Puppy," the over-40-foot flowering topiary sculpture, that’s presided over by Frank Gehry’s masterpiece, the Guggenheim of Bilbao, with its undulations rendered in titanium, glass and limestone.

The Basque wine region produces lauded Rioja wines.

The small town of Guetaria was the birthplace and hometown of Cristóbal Balenciaga, the influential fashion designer.

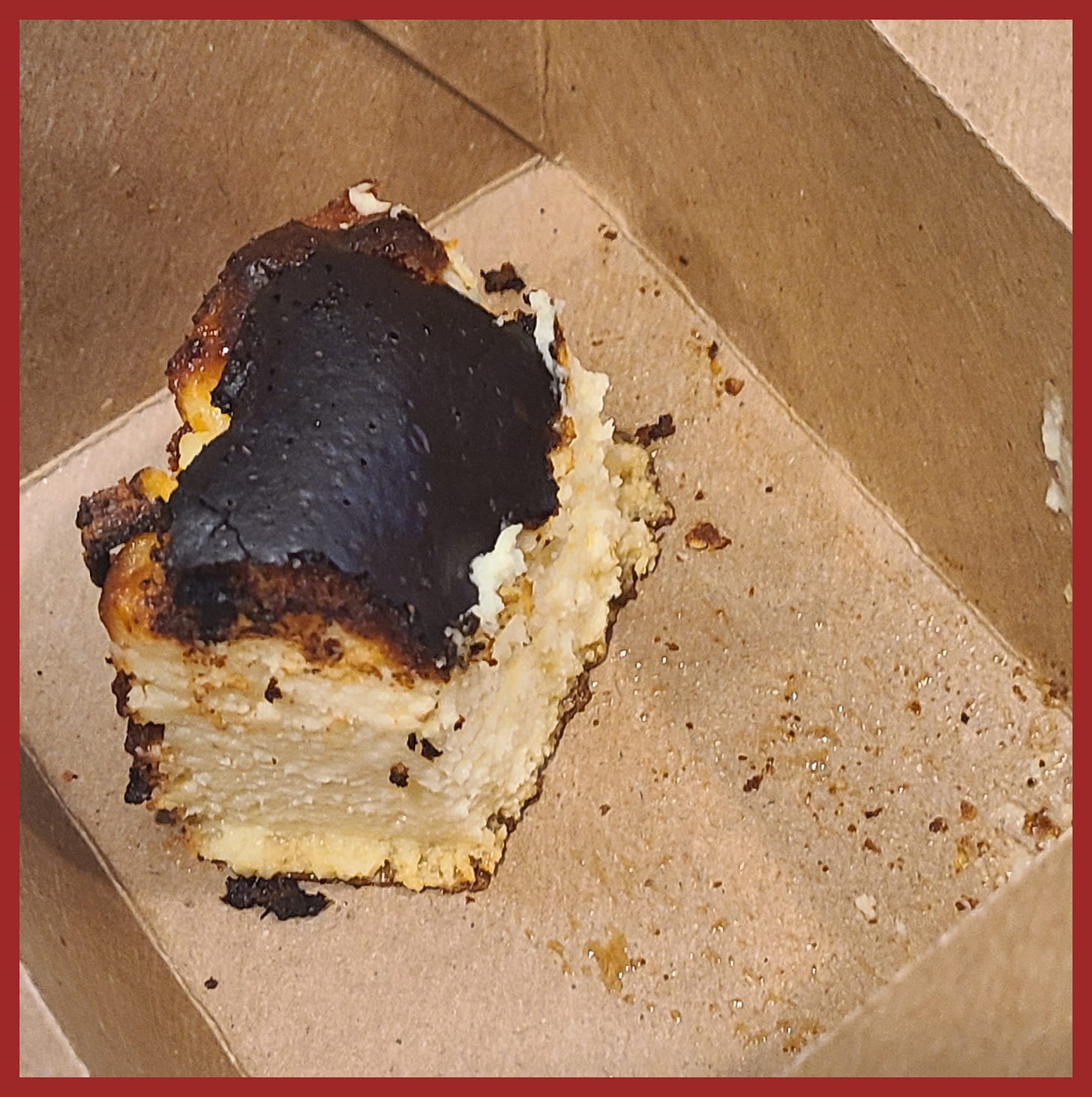

And then there’s the food. Of all the foods to come out of the Basque region, it's the cheesecake I can't resist. If you think burnt is bad, you’re sadly mistaken when it comes to Basque cheesecake. The crustless cheesecake is baked in a very hot oven so the top scorches to a dark, intense flavor and the center—slightly undercooked—is rich and creamy and vanilla-y. One birthday involved a surprise trip with my husband to a new-to-me L.A.-area bakery where Alan introduced me to my culinary obsession: Basque cheesecake at Valerie Confections.

I almost forgot to take a picture before I ate the whole thing.

Many Basques who came to the U.S. worked on sheep ranches. Some stayed and established ranches of their own. That’s the field trip I remember most. Going to a sheep ranch in our county at shearing time.

Basque immigrants who came to the Western U.S. have definitely made their mark and added to our wonderful diversity. Recently, I heard a story that added to my interest in Basque culture.

A large number of Basques came to California during the gold rush to work sheep in the High Sierras where aspens grow. The herders followed the sheep high into the mountains to graze all spring and summer, then return to the valleys in the fall. It's solitary work. The graceful aspens were companions to the men. The shepherds, lonely for Euskal Herria, their Basque homeland, began to leave etchings on aspens’ white bark. When the white bark is marred, it leaves black scars that remain forever on the trees. In the stands of aspens in the Sierras are living records. Arborglyphs. Black line drawings on white bark attesting to the universal yearning for home.

Some of the etchings are signed and dated. Some include the hometown of the carver. Some show the architecture of home. Some are graceful female nudes—wives or lovers left behind, maybe. The sights and smells, songs and language of home surely must have resounded in the hearts of the shepherds as they carved the images.

Home. It lives in our hearts forever. Sometimes the memories are sweet. Sometimes not. Sometimes the memories are written down. Sometimes they’re etched in tree bark.

There is in us a universal need to remember Home. I know it well.

My favorite Basque restaurant is Wool Growers in Los Banos. It's been years but I still remember the meal I had there with my then in-laws on our way to Cambria from Los Altos. What a heavenly treat!

What a treat this history lesson is. Thank you, Lucinda.