It was dark as hell, and a cold wind blew straight through Ruby’s red shorty pajamas. Her hair was up in rollers, covered by a matching red flouncy hair bonnet; she had one in every color. She was wearing a pair of cowboy boots and easing along the back of the house, feeling her way to find the panel box so she could flip the circuit breaker and get the lights back on inside, hoping to hell nobody came along and saw her looking so ridiculous. Inside the house, Myrtle, her mother-in-law, and Dorothy Pearl, her crazy sister-in-law and the bane of her existence, were both asleep, happy as if they had good sense. Oh, how she hated them and this godforsaken town.

Right now, Ruby about halfway wished her husband Willard had succeeded in pushing her out of his airplane over Palo Duro Canyon. Then she’d never have had to lay eyes on Claunch, New Mexico again. Or those two crazy bitches.

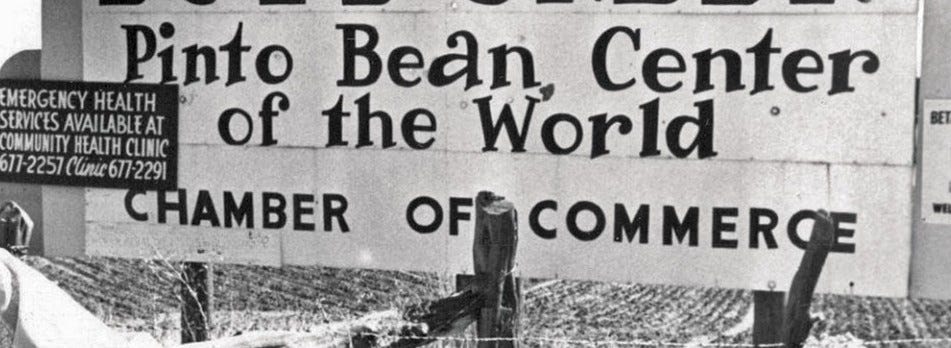

Claunch, she thought with disgust. A year and a half ago, she’d never heard of this wide spot in the road. Pinto Bean Capital of New Mexico. Former capital. Pinto bean farming dried up, literally, about 20 years ago, but the Pinto Bean Capital sign outside of town was still standing, and it was just one of the things on the list of things that irked Ruby about Claunch, New Mexico.

About smack dab in the middle of nowhere is where she was, saddled with those two nuts to take care of all day while Willard swanned around between here and the Texas Panhandle delivering airmail packages and, as she had just confirmed, cheating on her with various women in various towns along his route. A notable dalliance was going on in the small town of Dixon. As she thought about it, her black eyes darkened even more, if possible, and she set her mouth in a mad straight line as she fumbled along the back of the house hoping she didn’t step on a rattlesnake—that’d be the limit—and die of a rattlesnake bite in Claunch, New Mexico in the middle of the night with her hair in curlers, wearing shorty pajamas and cowboy boots. Well, why not? Everything else had gone wrong.

Ruby wasn’t meant to be relegated to such obscurity. Her parents had both been larger than life, and Ruby was born with the expectation of having a charmed and exciting life as well. But somewhere along the way, everything went off course. Ruby’s mother Seely was Osage Indian from Oklahoma, and her daddy Jack was Black Irish from Arkansas and looked just like Clark Gable. Having a daddy that handsome had clouded her judgement about men, and Ruby had admittedly made some poor decisions about men based purely on their looks. Her mother and father, Seely and Jack, met in Oklahoma around the time of the Osage Oil Boom. Seely had headrights to Osage oil royalties that made her rich beyond avarice, and in 1920s-era Oklahoma, she comported herself around the small town of Pawhuska like a tsarina. Seely was beautiful and tall like Osages are known to be, and she was fearless and arguably fearsome as her ancestors were also known to be, if only because the exuberance and irrepressible energy she put into living was almost warlike in its ferocity. There weren’t enough hours in the day, days in the week, stars in the sky or fish in the sea for Seely. She’d been to Paris and London and Egypt to see the pyramids and ride a camel. On the day Seely and Jack met, she had almost run him down in her Packard Twin 6 Roadster while he was crossing the street in front of the Rexall Drug.

Seely was driving with the top down when Zorro, one of her two fox terriers named Zorro and Hoodlum after Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford movies respectively, leaped from the rumble seat onto her lap, causing her to swerve maniacally from one side of the road to the other. By the skin of his teeth, Jack jumped out of her way and watched the red blur of the roadster roar past. He could hear Zorro and Hoodlum barking like heathens and Seely letting out what sounded like a primal war cry. Whoever she was, he was determined to meet her.

Jack could have lived off his good looks and charm alone, and he combined both of those considerable attributes with an uncanny ability to smell a good business opportunity. At the age of 25, he had already accrued a respectable amount of money and real estate. He had been in Pawhuska, Oklahoma looking into some business for the Midland Valley Railroad. It was a complicated deal they were trying to negotiate that involved mining and mineral interests in Indian territories—cutthroat stuff that Jack found he didn’t have the stomach or heart to do—so he was in the market for a diversion when the red roadster plowed past. He figured if the driver of that car continued south, she was heading to Tulsa, and his best guess was he’d find her at the Cave House, a “chicken restaurant” Pretty Boy Floyd was rumored to frequent when he was in the area and where, if you uttered the right password, you would be allowed access to a special area where whiskey was referred to euphemistically as Horse Liniment or Coffin Varnish.

And sure enough, about an hour down the road from where he almost met his maker, Jack saw the shiny red roadster parked right by the front door of the Cave House. So happened he knew the password, and when he strode into the familiar inner sanctum, he saw Seely perched like a vision on a barstool, wearing a cloche hat that all but obscured her face. Her red lips were pursed around a cigarette holder, and when she threw her head back to laugh, he could see black curls on each side of her face, framing a visage that he felt sure he would follow to Hell and back. Zorro and Hoodlum were racing up and down the bar, lapping up spilled Horse Liniment and making complete spectacles of themselves, while Seely laughed and laughed and threw her head back and laughed some more.

Seely and Jack and Zorro and Hoodlum took off two days later, heading to the Free State of Galveston. Galveston, Texas was wide open in the ‘20s, and the underground casinos and “cold drink places,” as the speakeasies were called, were a draw for anybody wanting to have a good time. And Jack and Seely had one hell of a good time swimming in the Gulf, dining and dancing at the supper clubs along Seawall Boulevard and gambling in the underground casinos that flourished under the control of Sam and Rose Maceo, the entrepreneurial Sicilian brothers who had turned Galveston Island into a freewheeling, luxurious tourist destination. On day 21, in honor of their luck at the blackjack tables, Jack and Seely—contrary to traditional Osage wedding rituals—got married at the famed Hotel Galvez.

Jack had no idea when Seely had had the time or opportunity to arrange it, but she appeared at 9 p.m. sharp in the ballroom, wearing a white satin wedding gown encrusted with bead pearls, carrying a bouquet of red roses with trailing Osage feathers, accompanied by Bix Beiderbecke and his orchestra, the Wolverines, playing “Fidgety Feet,” her favorite song. Their only child, Ruby, was born a year later—January 25th, 1925, a day after the birth of Maria Tallchief, the most celebrated of the five Indian ballerinas from Oklahoma who transformed the world of ballet in Europe and the United States. In the years to come, Maria Tallchief would glissade across Europe, and Ruby would two-step across West Texas. Maria would marry and divorce George Balanchine. Ruby would marry and divorce a rodeo cowboy. While Maria would dance to Stravinsky’s “Firebird” at the New York City Ballet in the title role created for her by Balanchine, Ruby would work for the telephone company in Amarillo, Texas. The complicated choreography of a switchboard operator would require almost as much grace and skill as that of a prima ballerina but hold none of the glamour or fame.

By the time Ruby was grown, the fortune she should have inherited was gone, lost somehow. She didn’t know the hows or whys, but it was hard for her to be bitter when she looked back and remembered Mama and Papa and all the places they’d gone, all the things they’d done. Even in the darkest days of the Depression after Jack lost every penny, Seely’s Osage oil money kept rolling in, and they remained a part of the very lucky few in this country who enjoyed comfort and stability.

But when little Ruby saw the bread lines in the cities and towns and on the roads—the hungry, hollow faces of little kids her own size peering out the back of Model T pickup trucks crowded in with their mamas and daddies, sisters and brothers, uncles and aunts, everything they could carry away from the Dust Bowl—she didn’t understand it, and it scared her. There was a lot she didn’t understand, but her pride wouldn’t allow her to ask questions and let on that she wasn’t as “in the know” as any other adult. She’d heard her daddy and mother joking about being Okies, but there was something in the way Seely looked when she said it. It was a sad and worried look she hadn’t ever seen on her mother’s face before, and it made her anxious.

And the Model Ts didn’t all go the same direction. Some of them were headed back East from where they came. Jack would say, “Well, I guess that ol’ boy didn’t have the Do Re Mi,” those same words she knew from a song she’d heard Woody Guthrie singing on the radio. She didn’t know it was talking about state troopers turning migrants away at the California state line. She just liked the tune, mostly because of Seely, who would always say Woody Guthrie was a great man. Then Jack would laugh and call her a pinko and tell that old joke for about the thousandth time about “How can you tell a rich Okie from a poor Okie?” “The rich Okie has two mattresses on top of his car,” and he’d turn to Ruby in the backseat and say, “Isn’t that right, Baby Girl?”

And that one time when they stopped at a filling station and Ruby went inside with her daddy because she knew he’d buy her a Coke and a bag of peanuts to pour in the bottle. As she reached into the ice water in the Coke machine all the way up to her elbow to fish out the bottle, she heard the men standing around making hateful remarks about Okies, and she felt sick and scared and stayed close to her daddy because she knew she was an Okie, a little Okie, and she hadn’t done anything to those men, but they made her feel uneasy anyway. Then of course she spewed some of the sweet salty Coke onto the front of her dress and Jack had to make a big deal out of dipping his handkerchief in the ice water and sponging her off before they got back to the car and the persnickety gaze of Seely. Ruby had to look just perfect all the time to please her mother. And her Daddy, too, if the truth was known, who was not only vain about his own looks but vain about his two girls.

Anyway, Ruby was beginning to get suspicious that something was bad wrong and that Jack and Seely were keeping secrets from her. But aside from that little nugget of suspicion in the back of her mind, she was having a ball and didn’t care that they never settled in any one place for long. She loved living in hotels for months at a time, all over the place, anywhere her mother got a wild hair to go. New York, San Francisco, Galveston of course, Miami, New Orleans. She was never lonely, even when Jack and Seely left her by herself while they went out on the town. She always had her little terrier to keep her company, and she made it a practice to charm the hotel staff who became her sometime babysitters, sometime playmates. Ruby was such a pretty little girl, charismatic and poised, she carried herself with a precocious independence and sophistication and gumption that rarely gave way to fear and almost never to tears—with one notable exception.

It was in the French Quarter in New Orleans late one night that she awoke with the feeling she was being watched. In the door of her bedroom, she saw the ghost of a little slave girl dressed in rags, holding a doll in her arms and singing a lullaby, the same one Seely sang to Ruby. “Bye, Baby Bunting, Daddy’s gone a-hunting, Gone to fetch a rabbit skin to wrap his Baby Bunting in,” the little girl sang. Ruby’s screams echoed down the halls and through the immense, ornate lobby. They could be heard, or maybe just sensed, down the street and all the way to the back of the grocery store that was a front for the speakeasy where Jack was playing high stakes poker and Seely, who’d been drinking Sazeracs, was doing the Charleston on top of the bar. By the time Jack and Seely arrived at the hotel, frantic and nearly out of their minds, Ruby had been calmed and comforted by the attentive hotel staff.

Jack and Seely promised never to leave her alone again, but they did. It was years later and she was by then a grown woman, but their loss, their death, was almost too much to bear for a child who had been part of such a trio, the littlest of equals. So, when Art Young, Jack and Seely’s longtime lawyer, read their will and she learned the news that she was broke, it was the least of the heartaches she felt. All she knew to do was get her grieving done and get on with her life, just like her Daddy had always said do.

Getting on with her life is what Ruby had always done, too, but this mess she’d gotten herself into now, this was too much. If the only thing making her unhappy was Willard’s philandering, she could fix that, but what she couldn’t fix was living in this godforsaken hellhole, Claunch, New Mexico. Willard would never leave his mother and sister, and the irony was that Willard’s devotion to his mother and sister had been one of the things she liked about him when they met that Friday night at the Blue Armadillo nightclub just eighteen months ago. That and of course his good looks, her Achilles heel. And then there was the whole romantic aspect of his having been a pilot during the war and, well, that was the stuff movies were made of.

Ruby and her girlfriends from the phone company never missed Texas Slim and the Fatboys out of Dumas, Texas who appeared at the Blue Armadillo every single Friday night on their way through town going to the Big D Jamboree in Dallas. The Big D Jamboree took place at the Sportatorium, where Texas Slim and the boys tore it up on the makeshift stage—that was actually a boxing ring—warming up the crowd for the likes of Carl Perkins, Wanda Jackson or Johnny Cash. But on Friday nights, when Slim played the Blue Armadillo, Ruby was the standout of her group. There was something different about her, like she knew things no one else knew. And of course, she did.

Willard was dumbstruck when he laid eyes on Ruby, twirling like a dervish on the dance floor. He’d never seen anyone so graceful or electric or exotic. Willard thought she looked like she belonged on a stage somewhere, not two-stepping to some half-assed country-western band from the Texas Panhandle. She was tall and slender and long-legged, with jet black hair pulled into a French twist and held with sparkling hairpins that matched a necklace and bracelet she told everyone were set with rhinestones but were really diamonds that had belonged to her mother Seely. She was wearing a black dress printed with huge deep red roses cinched in at her waist and a full circle of a skirt that took yards and yards of fabric to create.

When Willard took her into his arms for their first dance, she thought he was her dream come true, and he thought he never wanted to let her go.

Reality set in hard and soon after they married and Willard installed Ruby in his house in Claunch with Myrtle and Dorothy Pearl, leaving her with them every morning when he went on his airmail delivery route. Ruby liked to get up early with Willard. She’d make a pot of coffee while he got ready to leave on his runs and drink coffee and smoke cigarettes and listen to the radio in peace before the rest of the house woke up. Sometimes before he left, if a good song was playing on the radio, Willard would take Ruby in his arms and waltz her around the kitchen, reminding Ruby why she’d fallen for him back in Amarillo.

The dancing might have been a trigger for Dorothy Pearl, who hated Ruby with a purple passion for taking her brother away from her, because it was often after one of their kitchen dances that Dorothy Pearl had one of her spells. She’d sneak down the hall from her bedroom to the kitchen, tiptoeing and humming the tune to “I Ain’t Got Nobody and Nobody Cares for Me.” Unfortunately, Ruby’s radio drowned out the sound of Dorothy Pearl’s humming and allowed her to get the drop on Ruby. When Dorothy Pearl got to the kitchen, she’d slyly pick up the percolator off the stove, take a swig of scalding coffee right out of the spout, then ambush Ruby. Grab her in a death grip and try her best to choke the very life out of her.

There was never an official diagnosis of Dorothy Pearl’s particular mental condition. Everyone simply agreed she was crazy as hell. Luckily, Ruby was wiry and strong, but she worried that one day Dorothy Pearl would get the best of her, so she kept a series of two-by-fours hidden behind doors, in the broom closet, propped against the stove or icebox in the kitchen. Anyplace handy so she would have immediate access to the one thing that would bring Dorothy Pearl out of her homicidal trances—a good, hard whack across the back with a two-by-four. All this, while horrifying, was at least something to break up the numbing monotony that had taken over Ruby’s life.

The only other thing in Claunch that provided any entertainment were ol’ Mr. Skinner’s pigs. Otis and Faye Skinner owned the only grocery store in town, and they had a little piece of land just outside the city limits. Faye decided Otis ought to put the land to good use and raise pigs, which he didn’t have the first idea how to do, and soon after his new sow had piglets, they got loose. Those pigs were hellbent on humiliating poor Mr. Skinner. Months went by and the sow and her piglets remained on the lam, not fully feral, yet footloose and fancy-free. They rode the line between town and country freely, foraging behind the grocery store when they came into town and raging around, causing havoc before they went back out to the old bean fields.

Ruby’s mother-in-law Myrtle had hounded and nagged Ruby for months to go quilting with her and Dorothy Pearl over at Mrs. Williams’ house. Ruby had managed to resist the temptation to have that much fun, but finally, out of desperation for anything to do, she went, and it was worse than she’d imagined. Myrtle and a bunch of ol’ biddies from her church gossiped and hatched hateful rumors more than they quilted while Ruby sat in the sweltering heat, watching Dorothy Pearl out of the corner of her eye, listening for humming—when out of nowhere, the screen door flew open and that sow followed by four piglets came running in. They hooked a right and circled the dining room, where one of the piglets got tangled up in Mrs. Williams’ lace tablecloth, then they barreled into the front room and right under the quilting frame. Catching the precious unfinished quilt on the wiry hair of her back, the sow ran out the back door and down the street, jumped a ditch, losing the quilt, and headed out toward the bean fields. It was pretty much the best time Ruby had had since she came to live there.

But Ruby had some serious business to attend to—that dalliance of Willard’s that was taking place in Dixon, the little town on the Texas-New Mexico line—and she intended to catch him in the act. Ruby drove to Dixon in a pickup truck she borrowed that belonged to Eula Huff, a woman who ran a sprawling ranch—singlehandedly—outside of Claunch.

Eula was the one person in Claunch Ruby found interesting—fascinating, really. She’d been places—all over the country, all over the world. She never didn’t have an interesting story to tell, unlike most of the people Ruby encountered in the once-Pinto Bean Capital. Eula came into town once a week to drop off her ironing. She wore men’s clothes at a time when women didn’t wear men’s clothes, and she didn’t give a good goddamn what anybody thought about that or anything else she did. She was real particular about her clothes—shirts had to have double starch, pants had to have sharp, perfect creases. On her way out of town, she always stopped by Skinner’s Grocery. She’d hand her weekly shopping list to Faye and head to the back of the store where locals smoked, drank coffee and exchanged news. It was the only opportunity Eula had for social interaction, living alone as she did.

Ruby encountered Eula the first time at Skinner’s Grocery when she overheard her talking about her rodeo days. Eula had been a champion in her day and liked to compete in the men’s rodeo events because it was more challenging. Turned out Eula had known Ruby’s first husband, the rodeo cowboy, and had regularly bested him in calf roping, bareback bronc riding and even bull riding. Eula’s daddy had insisted she had to be better than any cowboy on the ranch if she was going to be a ranch hand.

Eula made an unusual choice of colleges and received an engineering degree from the University of California, Berkeley at a time when it was anything but a typical profession for women. She went on to work on a number of FDR’s New Deal projects through the WPA. It was while she was working in New York City with the WPA that she became interested in art—particularly the many muralists who created public and private commissions. Art and politics—frequent companions—were on full display with a controversial mural painted by Diego Rivera. The mural he created for Rockefeller Center with the image of Lenin set off a firestorm, and Eula found herself in the company of some of the actors in the drama. She got to know Rivera and became smitten with his wife, the tragic, charismatic genius, Frida Kahlo, and her friends and lovers including Georgia O’Keeffe. For a while, she found herself in their orbit at the famed Casa Azul, their home in Mexico. But Eula was called home when her father died suddenly, and she had to take over running the ranch. It was then she began to live a very different, solitary life. From time to time, Eula would mention a visit she’d made to see an artist friend who lived not so very far away and had a flair with cow skulls and flowers.

Eula was a crack shot with a rifle or shotgun and during quail season would bring in some birds as a gift to Otis and Faye. Otis began to drop hints, then as his pig situation escalated, he implored her outright to get rid of the unholy animals. Eula made a few vague promises, but Otis’s running humiliation at the hooves of the sow and piglets was too much fun to spoil.

Ruby made it a habit of visiting Skinner’s Grocery on the day Eula was in town so she could listen to Eula as she chain-smoked Camel cigarettes and spun stories that reminded Ruby of the exploits she’d had as a child with her mother and daddy, Jack and Seely. Ruby did wonder, though, about Eula’s love life. Where would she find a like-minded woman around here? It was hard enough for a woman to find a man. Anyway, it was Eula who lent Ruby her pickup to go to Dixon to spy on Willard.

Dixon was the last stop on Willard’s run, and Ruby figured he’d be up to no good. Sure enough. Ruby was on the lookout outside Powell Drugs, drinking a Dr. Pepper and eating a Peanut Rounder, when she saw him drive by with a petite blonde in the front seat next to him. She threw down her Dr. Pepper and loped down the sidewalk to the intersection just in time for the light to turn red. She could hear Ray Price singing “Crazy Arms” on the car radio—her absolutely favorite song to dance to, which further infuriated her—and she leapt like a jaguar into the car, landing in the backseat right behind the blonde.

Ruby sat there, chewing on her Peanut Rounder and calculating what to do next. Willard drove down the street, unnerved and calculating what in the world he was going to do next. Ruby began to ease her feet up the back of the car seat, knees bent and loaded like a spring. Then with swift precision, she thrust her legs forward, pinning the unsuspecting, homewrecking bottle-blonde against the dashboard. Willard threw on the brakes, further ramming the little Jezebel into the dash. Then he jumped out of the car, ran to the other side, and threw open the door. Ruby jumped out of the car, and the fight was on right in the middle of Main Street.

Ruby and Willard flew back to Claunch in a fury that escalated above an immense prairie dog town that stretched for miles outside of Amarillo. The battle climaxed above the steep red mesa walls of Palo Duro Canyon. It was clear that homicidal tendencies ran in Willard’s family when, in his rage, he reached over and began to try to push Ruby out the door of the plane. She flailed around, trying to get a toehold on anything she could. Kicking and screaming, she landed a few strong blows to the side of Willard’s head, and finally, as the plane started such a deep dive you could almost see the whites of the prairie dogs’ eyes, Willard was forced to pay attention to his driving, and they made it back to Claunch in one piece. Just barely.

Late in the night, as Ruby stood in her red shorty pajamas and cowboy boots squinting in the dark at the circuit box at the back of the house, she pulled on a tight, stubborn switch. A loud, dull thud sounded, and it was at that moment, just as power was restored to the house, that she made up her mind.

Early the next morning, Ruby picked up her suitcases and her little terrier Midge and walked down the street, past the old silo that had stored pinto beans back in their heyday and on to the post office that doubled as a bus station. Eula Huff was waiting in her pickup with the motor running. Ruby hopped in. They drove off, down the street and away from Claunch. Everyone in town would soon know she’d left Willard. There would be idle speculation about her and Eula. Gossip and rumors would spread. Willard would be humiliated. Ruby laughed and laughed and threw her head back and laughed some more.

Share this post