It had only been a few days since Jerry Dale started working the fountain at Powell Drugstore, and she was overwhelmed. Powell Drugs was located on the corner of Main Street and Avenue A. The fountain at Powell Drugs was not only THE place for teenagers to hang out after school, it was a lunchtime favorite for anyone who worked or had business at the courthouse across the street, a meeting place for the ladies in town, a stop for the sheriff to have pie and coffee. And on Monday, Wednesday and Friday afternoons, lucky little leotard-clad girls did grand jetés from Bette Marshall’s Academy of Dance four doors down to get complimentary scoops of sherbet—IF they’d stood straight and tall, held their stomachs in and shown progress since last week.

Mrs. Powell had given Jerry Dale only a cursory training session for the job, which included a brief introduction to the grill, a quick explanation about how to operate the ice crusher, a rushed demonstration on how to make fountain Cokes and Dr. Peppers by pumping a liberal amount of syrup into a cup before topping off with carbonated water and, in Jerry Dale’s opinion, completely cavalier instruction about how to use the big blender to make milkshakes and malteds. It was pretty much beyond Jerry Dale to comprehend it at all, much less actually take orders from multiple hungry and thirsty customers and fill those orders with as much haste as necessary to please them.

At present, the entire offensive line of the varsity football team was loudly occupying every stool at the counter, calling for elaborate confections, grilled this, grilled that. Jerry Dale …let’s just say she wasn’t coping well when Miss McDonald came in the side door and asked her for an especially thick chocolate milkshake for her father. He liked his shakes extra thick, and Doris McDonald, who was frantic trying to get her daddy to eat or drink anything, thought a chocolate shake might entice him. She didn’t know how long it would be before she lost him to the cancer. Her heart was broken, and she would do anything, anything to give him comfort in his last days or weeks. She stood at the fountain wringing her hands, nervous for having left him alone, even though she could be home just two blocks down Avenue A in less than five minutes.

Poor Jerry Dale. She was barely five feet tall, and earlier that afternoon, a big block of ice from the ice crusher had tumbled out and hit her on the head as she teetered on a stool struggling to turn the handle to produce a mere cupful of ice. She nearly fell off the stool she used to reach just about everything, including the tall mint-green milkshake blender that sat on top of the tall back counter. Ike Gibson, the handsomest man Jerry Dale had ever seen, was sitting in his usual booth smelling like Old Spice and razzed her saying, “That block of ice just about knocked your block off!” She made a mental note to be especially aloof to him the next time he came in, then another immediate mental note that she hoped he would continue to come in every afternoon and yet another mental note as to what cute outfit she would wear the next day, especially for Ike’s notice.

More than anything, she wanted to suggest to Doris that she take her father a Dr. Pepper float. She’d gotten the hang of making floats and pushed them as much as she could to her afternoon customers, but she didn’t have the heart to make the pitch to Doris, so she methodically began to combine what, to the best of her memory, were the ingredients Mrs. Powell had listed for milkshakes. She climbed onto her stool and precariously placed the stainless-steel tumbler that had chocolate syrup dripping off one side onto the platform and fired up the machine, spewing the contents of the tumbler as high as the high ceiling and all over herself. She was wearing her favorite dress, a sleeveless yellow-and-white cotton print that buttoned all the way down the back, and on the front of the full skirt were big pockets decorated with buttons matching the ones down the back. Just precious! And now it was covered with chocolate that was going to be a bitch to get out. Shit! Why that blender had picked now to malfunction, she couldn’t imagine. It didn’t occur to her that she’d forgotten to add the ice cream that would have made it too thick to spew.

She pressed her lips together, removed the tumbler from its platform and, with a shudder, added some more milk. Just the other day, Mrs. Powell had shown her the stainless-steel container that held the milk. When she took the lid off, there floating on top of the white milk was a big dead fly, its iridescent wings outspread as if in surrender to its fate. Without missing a beat, Mrs. Powell had dipped the fly off, dumped it in the sink and replaced the lid. Jerry Dale thought she might faint. The thought of using that milk for poor Mr. McDonald who everybody in town knew was dying’s milkshake made her head reel again—that and the fact that she couldn’t for sure remember the instructions to make a milkshake, much less an extra-thick one. Lord help! It was a Pure-D fiasco.

Jerry Dale blended and blended and blended some more, added more fly-contaminated milk, and in the end the cup of soupy mess she handed to Doris McDonald for her dying father was nothing short of a crime. She didn’t charge her for it, though, and put the 35 cents out of her own purse into the till.

It was about that time that Becky Fairweather came in the front door with her little son Skippy. Jerry Dale took a ragged breath. Oh, no. What would that little boy get up to today? Skippy ordered a cherry Dr. Pepper with extra ice, meaning Jerry Dale was fixing to be back up on that stool, cranking away at that big block of ice.

Becky and five-year-old Skippy were new to town. Becky had gotten a full-time job waitressing at the Ranch House Cafe. Tot Hecheverria, the owner, had taken a special interest in her and Skippy and kept a close eye on them both. Tot was like that, always taking in strays and giving them safe haven. The night shift was the only one available, but Tot had a spare room to the side of the main dining area with a cot and a television so Becky could work nights without having to leave Skippy.

Tot gave Skippy free rein of the place—maybe not the best idea. Skippy was a handful, a little man of few words with a stubborn streak. But he took a liking to Tot and Tot’s chicken-fried steaks and the spare room with the TV where he could pile up on the cot and watch westerns. And he liked the jukebox. Tot kept coins in an old Sucrets sore-throat lozenge tin stashed behind the jukebox so Skippy could play his favorite music anytime he wanted to. Skippy particularly liked Johnny Cash and Merle Haggard, which could have offered a clue to anyone paying close attention about his outlaw nature. Skippy was fond of pie, too, and Tot was known for his pies.

Skippy liked to sit at the counter in the late afternoon when the cowboys came in for coffee. It was the men’s appearance, the boots and hats, western shirts with the pearlized snaps down the front and on the cuffs, the faint smell of sulfur as the flick of a wrist lit a match that lit a cigarette, the smell of strong fresh coffee, remnants of aftershave lotion mixed with sweat and dust. It was the economy of words they used and the vibrations their low voices sent through the air. It was all of it combined that sent a distinct yearning straight to the little boy’s core.

When the cowboys came in, Skippy would look out the window at the pickup trucks lined up in front of the Ranch House, some with horse trailers attached—horses’ tails hanging out the back of the trailers, swishing back and forth, rhythmically keeping pestering flies at bay, their big, muscled rumps moving from side to side as they shifted their weight, sometimes stomping at the floor of the trailers. Skippy wished he could open one of the metal doors, step aside and let one of the huge animals charge backwards. Then he’d climb up and ride as fast as he could, out to where he could see nothing but sky and clouds.

Shortly after they arrived in Dixon, Becky had rented a room for her and Skippy in the big, rambling rock house that belonged to the two sisters Irene Guinn, the school lunch-lady, and Nola Williams. It was old-fashioned room and board—which suited Becky—and Mrs. Williams took on the job of keeping an eye on Skippy during the day so Becky could sleep. Maybe not the best idea. Skippy was a handful. Mrs. Williams made it a policy to keep quiet about some of the stunts he pulled to save Becky any more worry. She was counting on the fact that pretty soon he’d be in kindergarten.

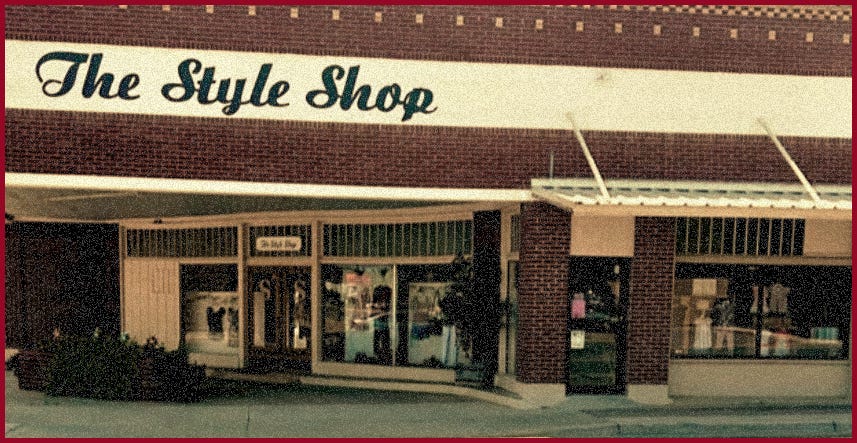

As much trouble as Jerry Dale had with her job at Powell Drugs, she liked it a lot. Her first day on the job she had celebrated by stopping by the Style Shop and putting a real cute brown-plaid shirtwaist on layaway. It was then she learned that the Style Shop owner, Viv Crosby, needed to hire someone to replace Flora Cole, who’d recently retired at age 87 because it had become more than she could do to get up and down and pin up hems. With Skippy about to start kindergarten, Jerry Dale thought it would be perfect for Becky to be able to work days, not nights, and arranged to have her meet Viv the very next afternoon. When she told Becky she’d set the whole thing up, Jerry Dale said, “And don’t worry about a thing. You can take all the time you need with Viv. I’ll watch Skippy.” Maybe not the best idea.

That next afternoon, little Skippy Fairweather was sitting in one of the big red vinyl booths up front drinking Dr. Peppers, licking a chocolate ice cream cone and scheming about how he was going to run away and never come back. It was during one of Jerry Dale’s many milkshake fiascos that he seized the opportunity, while all the ruckus was going on, to make his break. For a five-year-old, he was as brazen as a broad-daylight bank robber and possessed the steely determination and cunning of an escaping convict when he strode out the front door of the drugstore. He reached out and took a roll of Butter Rum Life Savers from the Life Saver display case, figuring he had nothing to lose. Might as well add theft to his list of crimes.

Simon’s Barber Shop was two doors down, and as Skippy strode past, the smell of bay rum and witch hazel wafted out the open door, along with the murmur of men’s voices and the buzz of clippers as Simon deftly created a perfect crewcut on the head of a pimple-faced teenager. By the time Skippy passed Randall’s Men’s Store, he’d adopted a little bit of a swagger to match his confidence. Nobody could stop him now, he thought, as he approached Don’s Boot Shop. Shoot, if he had the money, he’d go in there and buy himself a pair of Tony Lama boots like his daddy’s. And a pair of chaps with buck stitching and fringe.

Skippy headed toward the door of the boot shop. But at that moment he saw something that stopped him dead in his tracks. In the window was a sort of diorama. Painted on the wall was a completely lifelike mural depicting a cowboy galloping full-throttle—the horse kicking up a cloud of dust, the cowboy throwing a rope. The lasso hung in midair, and just in front of the lasso—standing in the window display, nostrils so close to the glass Skippy could practically feel its hot breath—stood a taxidermied two-headed calf. Skippy was mesmerized at the sight. Thunderstruck. Paralyzed. In all his five years on earth, he’d seen a lot of calves, yearlings, steers, heifers, even bulls being roped by the ranch hands he’d grown up around. There wasn’t anything that walked on four legs his daddy, Big Skip, couldn’t rope. But this! He stood frozen in awe at the sight of such an aberration of nature. There in the window, the baby white-faced Hereford calf’s four big brown eyes stared unblinking into Skippy’s own two big brown eyes.

Skippy was standing there transfixed, holding his dripping chocolate ice cream cone, when he was jerked up short by his shirt collar, as if lassoed himself. Becky stomped down the sidewalk FAST, leaving behind the poor little calf—who had most surely lived days shy of a week —watching after them with its four doleful eyes. She towed Skippy back toward the drugstore, swinging his arm along with her own arm so high he had to strain up on his toes to keep from being lifted off the ground. He knew he was in for—at the very least—a “good talkin’ to,” and he thought this time he might even get a spanking for running off and scaring his mother half to death. It wasn’t the first time he’d done it either, so he was pretty sure he might need to prepare for the worst. As they passed the barber shop, the teenager with the fresh crewcut was leaving, his transistor radio blaring Skippy’s new favorite song, “Pick Me Up on Your Way Down.” It didn’t occur to the little boy that it made the perfect musical accompaniment to the scene of his being dragged down the sidewalk in front of the whole town.

Becky threw open the door of the drugstore, picked Skippy up under the arms and flung him down hard on the seat of the closest booth. Jerry Dale flew from behind the soda fountain toward Becky, snatching a bottle of Miltowns off the shelf and practically beating her chest and intoning mea culpa, mea culpa. Becky grabbed her purse and began digging around in it for a cigarette, sighing with relief, panting with frustration and trying her best to calm her rattled nerves. That child, she thought. That child is a handful. And yes, he was. But the little guy was also carrying a burden way too much for a child.

Six months ago, life as Becky had known and loved it had changed so quickly and painfully, she was at times still numb. It was 5 o’clock in the morning when she got the news. She’d been up since 3 a.m. keeping steaming pots of coffee made and helping her husband Big Skip get out the door in the dark, wee hours to go to work. Skip Fairweather had been foreman of the Roadrunner Ranch for the last four years, and on this particular early morning, he had a long, dusty day ahead of him. It was spring—time to round up and brand cattle. When Big Skip went outside to join the regular ranch hands and extra hands that had been hired on, there was a general air of conviviality and excitement, as well as a collective acknowledgment of his authority. The hands ground cigarette butts into the dirt and pitched out last swigs of coffee before getting on horses that had been saddled and waiting, snorting what looked like smoke from their flared nostrils in the cold, dark, early morning hours. Men and horses alike were ready to work cows the whole long day.

A few hours later, Big Skip lit a cigarette and relaxed in his saddle, looking across the backs of corralled cattle, calves and cows mothered up, when he heard an orphaned calf bawling. A leppy calf, they called them. And he remembered his promise to bring his son another leppy calf to add to the tiny little herd Skippy was learning to raise. Way off in the distance, black thunderheads loomed, and, although any imminent threat of rain had passed, lightning could still be seen in the far-off sky and the low rumble of thunder still heard. Big Skip was carrying the bawling calf toward the corral when a loud clap of thunder spooked a big heifer. She snorted and lurched sideways, catching Big Skip on the side of his head with her powerful head. The blow sent him into the air, and he landed in the dust. He was dead in one dreadful instant.

Cows are dangerous to be around, and accidents happen. It’s a fact of ranch life but not a truth Becky was prepared to face on that early spring morning.

The Roadrunner Ranch belonged to Jack and Robena Ward. Big Skip and Becky were like their children. They doted on Skippy like a grandson. Robena was hardened to the realities of ranch life—deaths, injuries, hardships—but it broke her heart to speak the terrible words and watch helplessly as Becky’s face twisted into a mask of pain.

It was through the din of her own screams that Becky heard her little son crying, “Mama, Mama.” His little arms were outstretched, and she could make out the print of his pajamas: cowboys and horses on a soft blue flannel background. It was the sight of her now-fatherless son that staunched her wails and moans. Becky Fairweather took her baby into her arms to comfort him, reassure him and ultimately to break his little heart when she told him his daddy was gone.

Jack and Robena begged Becky to stay on at the ranch, but Becky, who was unsure of everything else, was sure of one thing at least. She and Skippy had to go. She could not endure the sight of another sunrise over a stretch of land dotted with cows and windmills, the sound of horses snorting and neighing, the smell of leather and tobacco, the taste of black coffee and Big Skip’s favorite early morning biscuits and gravy in the house where her husband no longer was. She would move to town. Take Skippy to a different environment, a place where they could just get on with living without the constant reminder of what had been.

The hardest moment for her was the day before they left. Skippy bequeathed all his leppy calves to his best friend, Augustin Olivas—Little Gus he was called—the grandson of Raul and Maria Olivas, whose son Augustin Sr. was killed in action in France in 1943. Raul and Maria had been the caretaker and cook for Jack and Robena for decades. They were family. Becky watched as Skippy and Little Gus stood solemnly looking over the calves, then shaking on the deal just as they’d been taught to do. Strong little men. Skippy said, “Adios, mi amigo.” Little Gus answered, “Goodbye, my friend.” In their child’s world, they didn’t expect to ever see each other again. Skippy’s cheeks glistened as he walked toward the house, but by the time he came through the door, he’d wiped his tears, pulled himself up and announced to his mother that he’d tended to his cows, and they could go now.

Viv offered Becky the job at the Style Shop. Becky knew it was the right thing to do to take the job. What she hated doing was telling Tot. But when Becky came to him with the news of her new opportunity, he gave her his whole-hearted blessing, as long as she promised to come back if ever anything went wrong.

Everything about Becky’s decision to work for Viv Crosby went right. Becky’s personal life was different, though. It was Skippy. It was always Skippy.

The Roadrunner Ranch wasn’t so far away, and everyone in Dixon knew what had happened to Becky and Skippy. People looked out for the broken-hearted little boy, knew to be on the lookout for the habitual runaway.

There was one particular runaway attempt that got the whole town involved. It was a little after noon on a school day when Skippy should have been in kindergarten. He slyly sidled through the door of the Ranch House Cafe, his cowboy boots scuffing across the wood plank floor, then slipped into the spare room with the cot. He plopped down under the air conditioner to cool off and put his feet up next to the TV. The cowboy hat he wore against the early September sun was pulled down low on his forehead, giving him a little bit of a five-year-old’s version of a devil-may-care, James Dean in “Giant” look. He had a rolled-up Dallas Cowboys blanket and a burlap sack with something wrapped up in it. And he had a white dog with him—a rat terrier. It was Nola Williams’ beloved rat terrier, the very same rat terrier that slept at Nola’s feet, followed her everywhere she went, stayed curled up in her big kitchen while she baked bread or napped on a pallet in the living room while she crocheted. Nola Williams and that dog were inseparable.

Ike Gibson rented a room at Mrs. Williams’, too. He stopped by Powell Drugs that afternoon long enough to tell Jerry Dale about the missing rat terrier, White Socks. Ike was part of a search party looking for her, and he told Jerry Dale to alert everyone who came into the drugstore to keep an eye out for Nola’s dog.

Tot had been making hot rolls in the kitchen of the Ranch House and listening to the radio when he heard the sound of Skippy’s boots scuffing. Possum Smith, the radio announcer, had just interrupted the County Agent’s weekly farm report with the breaking news of White Socks’ disappearance. Tot was shaking his head as he pushed through the swinging door, leaving a big handprint outlined with flour. No one was around, but he noticed the blue light of the TV glowing in the spare room. He looked in. Saw Skippy. Then he spotted White Socks shaking Skippy’s burlap bag, causing the contents to scatter across the floor, revealing a framed picture of Big Skip Fairweather roping a calf. Skippy snatched up the picture and wrapped it back as tightly as he could, never noticing Tot at the door.

Tot came in and pulled up a chair opposite Skippy and White Socks and said, “Hey there, Hoss.” Skippy merely nodded. Tot asked, “Where’s your Mama?” Skippy said matter-of-factly, “Work.” “How’d you get here then?” “Walked.” Tot knew he had to handle the situation gingerly. Tot also knew what the five-year-old boy didn’t know. Skippy wasn’t running away. He was running toward something that he would not find—his father, Big Skip.

Years passed. Skippy never knew what he was searching for. He dropped out of high school, took work on ranches, followed the Pro Rodeo circuit for a while. He took jobs on the oil rigs that dotted the plains around Dixon, dangerous work but not as dangerous as the offshore rigs he began to work.

Still—always—a piece of him was missing. Grief and chaos tore at him. The whole country, too, was torn by the grief and chaos of a war that was being fought by young men like Skippy, thousands of whom died in jungles and were brought home in flag-draped coffins, while others marched in the street and made small but defiant bonfires with their draft cards.

Becky Fairweather’s angry young son ran away once again. Still a man of few words, he left without telling a single soul. Not his mother, not anyone. He enlisted to fight in a war that had turned the country inside out. This time, Skippy ran half a world away. It turned his mother inside out.

What saved Becky’s sanity —sometimes —was the Style Shop. Really, that job had been her lifeline all along. She and Viv had always been perfect partners. Becky was innovative and industrious, and soon Viv was able to slow down and place a lot of the business into Becky’s capable hands. And before long, she felt good about retiring and leaving Becky to run the shop.

There had always been talk about Becky. Unsolicited opinions that if she spent less time at work and more time with Skippy… Criticism that wouldn’t have dogged a man, and she knew it. She knew, too, that it wasn’t her job that was the problem. It was Skippy. If she had only known how, she’d have done anything.

Becky never let anyone’s criticism slow her down, though. Skippy wasn’t the only Fairweather who was strong-willed. Becky’s ideas and innovations for the Style Shop transformed it into a kind of High Plains fashion mecca. Dixon was a small town, but many of its population were well off. There were plenty of women who had the means to take shopping trips to Dallas and New York, and did. But the well-heeled women liked having a fashionable place to shop close by, too, and Becky knew it. She made her clientele feel special in every way she could—a phone call to say she had put back half a dozen dresses that had just come in or a pair of shoes that would go perfectly with the suit they’d bought the week before. On a buying trip, Becky saw a line of little girls’ Italian suits like the women’s suits she sold at the Style Shop. She stocked as many of them as she could get her hands on, and they flew out the door. Becky had keen instincts.

Becky didn’t remarry after Big Skip died. She had men in her life, but she liked her independence and enjoyed her own success. There were newspaper articles and features in women’s magazines from Albuquerque to Dallas written about her. She was becoming a part of a new breed of woman in the country—the kind of women who inspired the oft-quoted line, “A woman needs a man like a fish needs a bicycle.”

When Skippy’s letters stopped coming, the Style Shop was the only thing that kept Becky going. Saved her life, really.

On a hot June afternoon, Becky closed up the shop early. As she turned the key in the heavy glass door, she saw the image of Viv reflected there, her brunette hair shot through with gray. Then she realized it was her own image she saw. Had she really aged that much?

There was an almost magnetic pull that drew her along past the bustling post office and toward Main Street. Not so surprising, considering where, why and to what she was heading. As she approached the corner, she saw a crowd gathering a few doors down from Powell’s Drug, where many years before she had nearly collapsed in a heap after locating her runaway son.

She pushed her way through the cowboys, the well-heeled ladies and businessmen, the little ballerinas with their scoops of orange sherbet so she could be up front. So she could hear her son, Skip Fairweather Jr., announcing his candidacy for state representative. Skippy had found his way in the darkest days, most hopeless hours, longest nights. He had seen other broken young men, broken bodies. And improbably, in that jungle of broken spirits, he found the missing pieces. In the chaos, he wanted to run toward something. All the Jack and Robena Wards, the Viv Crosbys, the Tot Hecheverrias. He wanted to repay them somehow.

He wasn’t fully whole or fully healed. But he was home for good now. Standing there by the door of the boot shop in front of the two-headed calf that years ago had witnessed his undoing, Skip Fairweather Jr. committed to serve a community that had served him and his mother so well, so faithfully, for so long.

Share this post