The bell over the door of Powell Drugstore tinkled just as Jerry Dale Griffin was getting ready to close five minutes early and hurry to the library a block away, “Oh, for Pete’s sake,” she hissed as she saw Sue Woodruff coming through the door. Sue’s major talent was being indecisive. Just last week it had taken her more than a half hour to decide between two different home permanent kits—the Toni kit she’d used for years or the new push-button Lilt. The drawn-out transaction had caused Jerry Dale to miss an opportunity to wait on Ike Gibson at the soda fountain. Ike could coax a laugh out of her even when she was doing her best to play hard to get—especially then, it seemed. He’d started coming in the drugstore about a month ago, almost every day, and it was obvious he was coming in to see Jerry Dale. But he was about to run out of credible excuses for these almost daily visits. Today, he’d used the flimsy pretense of needing another can of shaving foam. Jerry Dale knew he must have a trunkful of shaving foam because she’d sold him three cans in the last two weeks alone, but his limited imagination was the only thing Jerry Dale could find wrong with him.

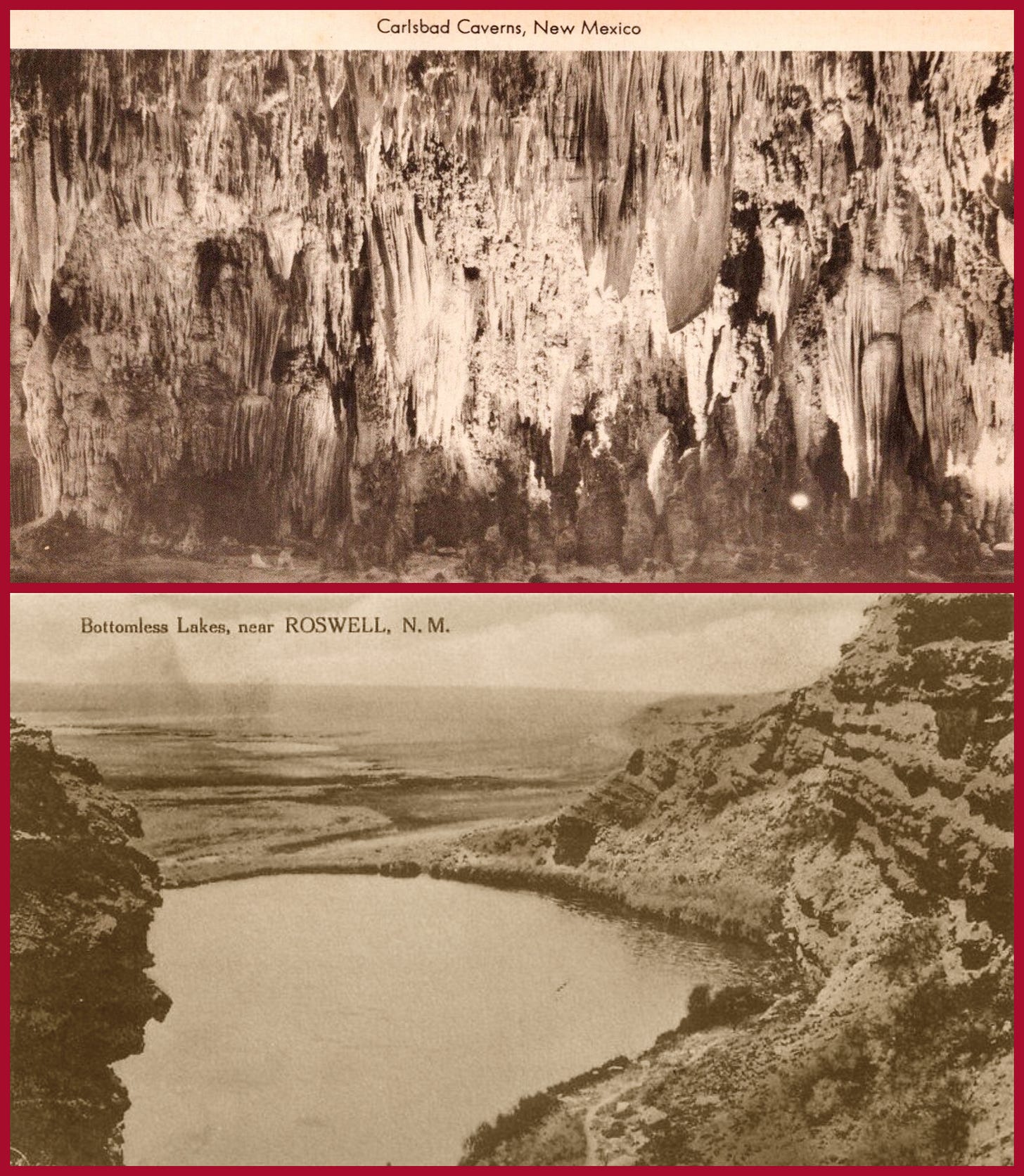

There was a lot going on in Jerry Dale’s world right now. It was the end of her senior year of high school, and her senior class trip was approaching. The class had been given two destinations to choose between, and they were to cast their votes in homeroom tomorrow. The choices were the Carlsbad Caverns or the Bottomless Lakes. Both options were objectionable to Jerry Dale, for different reasons. First, she was claustrophobic. The thought of dark, damp caverns made her nervous. As for option two, the Bottomless Lakes, Jerry Dale feared water. And bottomless water—unthinkable.

Jerry Dale’s fear was rooted in an incident that happened when she was five years old when her brother’s best friend and fellow heathen, Rusty Kindricks, had pushed her backward into a windmill pond. The memory of it was burned into her mind. It was on the afternoon that Jerry Dale’s mother Maudie had taken her and her brothers and sisters to have their pictures made. That alone had been an ordeal because getting them all dressed to suit Maudie was no small task. But besides that, Maudie had taken Jerry Dale to the beauty shop beforehand, where her little five-year-old head and red hair had been put through a torturous ordeal called marcelling, a terrifying process that used hot tongs to create rows of waves close to the head and came with the warning from her mother that if she didn’t sit perfectly still, she could easily get an ear burned off.

Jerry Dale had sat straight as a poker for over an hour to get the hairstyle that matched her mother’s fashionable waves. Even then Floy Sue, Maudie’s beauty operator and confidante, had slipped with the hot tongs for a second when she turned to Maudie to comment on another customer and the marital strife she was going through—seems her husband was trifling on her and she was strapped with four kids—stairsteps—and didn’t have the wherewithal to leave the sorry so-and-so—and that was the part where Floy Sue’s hand slipped and burned Jerry Dale’s neck. She let out a scream that didn’t so much as faze Floy Sue or her mother. Jerry Dale learned right then that beauty did not come without discomfort.

She did feel awfully pretty, though, when it was her turn to pose—as she’d been instructed to do—looking over her shoulder and smiling into the camera. The photographer’s face was completely obscured behind his powerful white light. His hearing must have been impaired, too, because when she muttered through her smiling lips that the rabbit collar hurt like hell where it rubbed the burned spot on her neck, it didn’t so much as faze him—or her mother.

When they all got home, Jerry Dale raced out to the windmill pond with her brother Buddy and perched on top of the pipe that ran from the windmill and streamed fresh water into the pond. She let her legs swing back and forth, showing off her black patent shoes. The blue plaid fabric of her dress exactly matched her deep blue eyes. The wind kicked up the skirt of her dress, making it flutter, but her marcelled hair didn’t move. Those waves were sculpted like granite across her forehead until Rusty Kindricks came running up. With one big shove and a guffaw, he pushed her backward into the muddy water. She hit the water with such an impact the outline of her body stayed visible as she sank below the surface. She reappeared, gasping, and began to flail and scream, clawing her way back up and onto her feet and stumbling up the slippery bank. She stood covered in mud from head to toe. Her rabbit fur collar was soaked, no longer white but dingy brown. Her dress clung to her body in one wet, dirty sheet, and her hair hung straight down over her eyes. The curls she’d suffered for were gone. She stood on the bank, bedraggled and stunned. She took a ragged breath. Then, blind anger started to boil up from deep within her gut. A red hole opened in her mud-covered face, and she let out a holler. Like a tiny, mud-caked banshee, she flew toward poor unsuspecting Rusty Kindricks, and leaped onto his back. She locked her legs around him and began to thrash him with her little fists as he took off running across the pasture, screaming. When Jerry Dale’s brother finally caught up with the conjoined pair, it was all he could do to bring them down. He took a beating, too, before he finally got his friend loose. But the episode made such a good story, he retold and embellished it for years, always ending dramatically with, “And I swear if I hadn’t got there when I did, she’d have surely killed my best friend!”

On that afternoon years later when Jerry Dale got loose from Sue Woodruff and closed up the drugstore, she had little time to spare and hurried over to the library. Her intention was to look through some of the travel brochures she’d seen on a rack way at the back by the reference section. She’d decided that some research might help her choose the lesser of the two evils her class had been given for their senior trip.

The only car parked in front of the library was an old blue-gray Studebaker that belonged to Ellen Sizemore, the Dixon city librarian. Sitting in the passenger seat with her head buried in a book was Wanda Sizemore, Ellen’s daughter. Jerry Dale knew the Sizemores well—they lived just next door. Ellen Sizemore was a widow—she said—but in truth, Mr. Sizemore had left her without so much as a goodbye or a forwarding address soon after their twin daughters were born. Ellen invented a preposterous story about his untimely death in, of all things, a plane crash while on a “business trip abroad.” Everybody knew Howard Sizemore had never so much as hit a lick, much less had business ventures of any kind abroad or anywhere else, but out of politeness, no one challenged Ellen’s account.

Ellen Sizemore had bought the Studebaker from Jerry Dale’s father. Red Griffin had no sooner pulled into his driveway in a new Dodge station wagon big enough to hold his sizable family, than Ellen Sizemore had dropped the kitchen curtain and beat a path to his door to inquire about buying his old Studebaker coupe. “For a fair price,” she emphasized, adding that it was just what she needed to get around town. “Especially,” she said proudly, “with Vonda about to go off to college.”

Ellen had two daughters, Wanda and Vonda—twins, “identical” ones she insisted—and an odder pair of twins you wouldn’t find. They did look exactly alike, but Wanda was a good head taller than Vonda, and Ellen described her as “well…slow.” Jerry Dale for one had her doubts about that. She and Wanda had been playmates when they were little, up until Jerry Dale’s mother Maudie died. Then their friendship fell away as Jerry Dale took on the responsibilities of being a surrogate mother to her little sisters. But it always seemed to Jerry Dale that Wanda was merely quiet, calm and thoughtful, while Vonda, “the pretty little twin” as Ellen described her, was loquacious like her mother and had her mother’s birdlike mannerisms. Seeing mother and daughter together was like watching a pair of clucking hens, while Wanda always stayed quiet in the background. If Wanda did venture to express herself, Ellen would more often than not loudly chide her, not caring who heard. “Wanda, big as you are, you really need not call unnecessary attention to yourself.” It was cruel and unfeeling and—from the hurt look on Wanda’s face and the way she slumped over to hide her offending size—humiliating. Everyone felt sorry for her, and Jerry Dale couldn’t remember a time when anyone called her name without adding “Poor Ol’” to it. Poor Ol’ Wanda this and Poor Ol’ Wanda that. Poor Ol’ Wanda Sizemore.

Jerry Dale kept her eye on Poor Ol’ Wanda sitting there in the Studebaker as she approached the front door of the library, opened it slowly and carefully began to ease through it. As she did, a hot gust of wind caught her hair and blew it straight up into a titian-colored column; she might as well have sent up a flare. She closed her eyes for a second and held her breath. Then, glancing both ways to see if the coast was clear, she tiptoed past the front desk toward the back. The library was nearly empty, so she knew Ellen Sizemore would be on high alert for anyone coming into her domain. Ellen was busy shelving books when the door pushed open, letting in enough hot air to raise the temperature and change the barometric pressure of the library so minutely that only some kind of meteorological savant could have detected it. Ellen brought her book cart to an abrupt halt and, in a hen-like move, jerked her head slightly to one side and froze. Then she telescoped her head around a shelf marked 800 for Literature, and, in a voice ironically thunderous for a librarian, she brayed, “Hello! Somebody there?” Jerry Dale froze in an animal-like pose of her own, then jumped sideways behind the rack of tourism brochures. A metal prong on the rack snagged on her sleeve, causing the whole rack to rock sideways and teeter on its base. Jerry Dale willed it not to topple and tip off Ellen. More than once, Jerry Dale had endured a tedious explanation of the Dewey Decimal System, with which Ellen had an almost religious relationship—she lived by every tenet of it. So, when the rack stabilized, Jerry Dale grabbed a handful of the free brochures, glued herself to the back wall, slid all the way around the perimeter of the building and made her escape.

Now that she had some good information to consider, Jerry Dale could decide between the two destinations—a choice between a rattlesnake and a Gila monster, she thought, but better to be informed.

Jerry Dale had a particular reason to look forward to the trip. Taking care of her younger brothers and sisters since her mother died had been a heavy weight for someone so young. Seven motherless children in all—Jerry Dale just 14 at her death and her baby sister not quite three. Plenty of do-gooders had poked noses in with suggestions that would have split them up, farmed them out to various family members and other willing families. The thought was untenable to Jerry Dale, even though the responsibility of caring for them was at times overwhelming. She wouldn’t have had it otherwise. The truth was this was the real reason Jerry Dale disliked Ellen Sizemore so much. Ellen had been part of a cabal of church women who had come up with a scheme to split up Jerry Dale and her siblings, and they were very nearly successful in convincing her father it was for the best. Jerry Dale had fought tooth and nail to prevent it, but the fear of it lingered and haunted and kept her awake nights, trembling with dread and holding tight to her baby sister, Martha June, who slept holding Jerry Dale’s earlobe between her little fingers. It would take more than Ellen Sizemore and a gaggle of women from the Church of the Nazarene to split up her family. Jerry Dale vowed she’d die before she would ever let it happen.

The travel brochures painted lovely pictures of both the Carlsbad Caverns and the Bottomless Lakes State Park. Turned out the lakes were not lakes at all, but sinkholes—also called cenotes—that formed along the base of what is known as the Seven Rivers Formation. Water from an artesian aquifer dissolved the gypsum-rich earth and created the mysterious bodies of water. When cowboys exploring the area came across the nine lakes, they tried to gauge their depth by tying long pieces of rope together, but when their attempts to hit bottom failed, the sinkholes were declared bottomless, and the eerie label stuck.

Jerry Dale decided to shift her attention to the brochures about the famed Carlsbad Caverns, which at this point seemed like a much better choice. According to the literature, the natural beauty of the Caverns is so impressive it was designated a National Monument by President Coolidge in 1923. Interesting descriptions of the ancient history and formation of the many interconnected areas of the whole chain of caverns and the mysterious stalactites and stalagmites looking like pieces of abstract sculpture all caught Jerry Dale’s fancy—until the part about the bats. Millions of them. Hordes of bats call the caverns home and fly from the mouth of the caverns each night in immense swarms to feed on insects before returning at dawn to the Bat Cave, one of the large, interconnected rooms where they resume their upside-down dangling in dense groups until sundown the following day.

“Well, okay, I’m voting for the lakes,” thought Jerry Dale.

And the next day, by one vote, it was decided that the senior class trip would be to the Bottomless Lakes State Park. Relieved, Jerry Dale figured if things went according to her plan, she would simply avoid the water, find some shade and enjoy a day of picnicking and fun with her friends above ground.

The day of the trip came. A genuine air of excitement and fun took over the bus packed with kids, teachers and chaperones, picnic baskets, folding tables and chairs, and big metal ice chests, some packed with bottles of Coca-Cola, root beer and Orange Nehi, others with containers of potato salad and foil-covered pans of cold fried chicken and fruit cobblers. Many brought gallon water coolers—Jerry Dale’s was a red Scotch plaid gallon-size cooler she’d filled with lemonade she got from Mrs. Powell at the drugstore. She had a matching round picnic cooler that was sturdy enough to use as a stool when the lid was on tight. Inside it, she had a big foil-wrapped package of golden-brown chicken that Louella Filby had fried up in big cast iron skillets early that morning. And Louella added a surprise: a batch of apricot fried pies, Jerry Dale’s favorite.

Some people described Louella Filby as a nervous wreck, mostly because she was scrawny and had sharp, tense-looking features. Her thin lips seemed to always be pressed together, as if those lips alone were keeping her from flying to pieces. But frail-looking or not, Louella was a stalwart figure in Jerry Dale’s life and the life of Jerry Dale’s family. She was a distant relative of Jerry Dale’s mother and had always been willing to step in to help in any way she could, both before and after Maudie died and left seven children motherless.

Early that morning, Jerry Dale’s father had waited impatiently in his pickup, motor running, to drive her to the school gymnasium to catch the bus. Jerry Dale was running late. As she struggled to carry both heavy Scotch plaid picnic accessories, Louella protested from the kitchen door, “My Lord, Jerry Dale, you look like a pissant carrying a big crumb.” Jerry Dale glanced back and answered, “I’m fine.” Louella yelled one last time as they drove away, “You look awful pretty in that little dress. Watch out you don’t wrinkle it, and y’all be careful now.” Jerry Dale had her hair pulled up off her shoulders and piled up on top of her head in a pretty bouquet of strawberry-colored curls. She was wearing a lemon-yellow checked sundress that tied at the shoulders with white appliqued daisies on the bodice and white leather sandals with straps across the front and a strap buckled around her ankles. She carried a white straw purse and a matching white straw hat that tied under her chin so she could secure it against windy mishaps. The hat was the only thing that offered the least bit of protection for her white skin. Jerry Dale was so fair-complected, she could burn through her clothes—even windburn—but Louella had convinced her to pack one of her daddy’s big khaki work shirts to wear over her dress if, in the worst-case scenario, she found herself caught out in the sun.

The day started off fine. When the bus arrived, everyone headed to the picnic tables to set up, then eventually began to break up into groups to rent boats or swim or wade in Lea Lake, the only one of the nine lakes where swimming was allowed. At one point, Jerry Dale looked around and realized she was alone under the shade except for Poor Ol’ Wanda Sizemore, who was sitting in a camp chair reading a book. Jerry Dale pulled up her Scotch plaid picnic cooler next to Wanda, sat down on it and said, “Hello.” Wanda was so startled, she nearly toppled off her chair. Recovering, she said, “Oh, hi, Jerry Dale,” and went back to her book. “What’s that you’re reading?” Jerry Dale coaxed. “Oh, this?” Clearly pleased to be asked the question, Wanda began a long description. “It’s a book about seismic activity along the San Andreas Fault in California.” Jerry Dale had a Dewey Decimal System déjà vu moment as Wanda went on and on, finally wrapping up by saying, “I intend to visit California after graduation. The whole western United States actually.” “Oh,” said Jerry Dale. “Well, that’s”—she was about to say “interesting” when she saw that her pretty white straw hat was skipping along the ground, pushed by a breeze and headed straight to the water. She took off after it, but with each lunge, she just missed. It skipped along onto the wooden boat dock, continuing toward the brackish water. Jerry Dale took a last leap. She misjudged by enough to land herself in a precarious position. Half her body landed on the wooden dock, the other half hovered over the dreaded water. She dug the toes of her white sandals into a crack in the wooden planks and used all the strength she had to drag herself from the brink. Splinters tore at her legs. When she could at last reach behind her and feel the dock, she managed to pull herself up to her hands and skinned knees, then stand up. She reached the back of her hand to her forehead. The heat and fear made her dizzy. She reeled—then fell into the murky, brown water of Lake Lea.

When she hit the water, it wasn’t just her body, face and carefully done hair that sank below the surface. It wasn’t just the smart, yellow-checked sundress and strappy sandals that were submerged. It was her whole being. As if watching herself in slow motion from above, Jerry Dale saw the years of her life wash over her as she sank into the brown lake water. She could see a young girl who’d lost her mother. She saw the older but still very young woman who had taken on the burdens and responsibilities her mother had left behind. It was more than dirty, tepid lake water that washed over her. It was the memory of that day so long ago when she’d sat waiting with her mother for the photographer to call them in. Nestling on her mother’s lap—her beautiful vivacious mother. Resting on her ample bosom. Turning over the paws of the stone martens that lay around her mother’s neck. Stroking her own white rabbit-fur collar. Considering the fancy marcelled waves in her red hair that matched her mother’s undulating brunette waves. Imagining how the portrait would turn out and how pretty they would all look.

Jerry Dale must have lost consciousness when she hit the water, but when she realized she was sinking, she began to claw the water, trying to avoid the fearsome bottomlessness of it. But with each frantic reach and flail, she sank further. A determination, fueled by a familiar feeling of rage, overtook her until she finally surfaced —only to sink again and again. Someone grabbed her from behind, and, instead of allowing the helpful hands to pull her to safety, she fought and kicked and pounded until a blow from the unknown rescuer knocked her into unconsciousness again.

When she came to on the bank, she was covered in mud. Tendrils of aquatic plants wrapped around her ankles and lay across her face. One of her sandals was gone. A ring of faces formed a circle above her. She registered the looks of horror and concern, but it was minutes before she could finally discern their identities. What she was not able to discern were her feelings. Was she grateful to be safe or was she sorry she hadn’t simply drifted away, down and down, back to the safety of her childhood and into her mother’s loving embrace?

On the long, hot drive home, Jerry Dale sat silently wrapped in her father’s khaki shirt. Next to her, wrapped in a red-and-white oilcloth tablecloth, sat Wanda Sizemore, vigilant, silent and still. Her hair was wet and muddy. A bruise spread across her cheek where Jerry Dale had pummeled her rescuer. Wanda’s protective presence created an aura of safety. Jerry Dale clung to it. Her mind began to focus on the present and the future. The things in front of her instead of the things of the past. And mostly, she thought about Ike Gibson. It was on the long drive back to Dixon that Jerry Dale decided she intended to make her life with Ike. Even though he hadn’t so much as asked her on a date, she knew there would never be anyone he would want more than her, no one he would ever love as much. She knew they would build a life together. Her lips formed a faint smile. She closed her eyes and dreamed of the possibilities ahead.

Ike and Jerry Dale married a year later. The only guests that could fit in the small living room of her father’s house were her father, four sisters and two brothers. Vernon Henry was Ike’s best man, and Trixie Henry, nine months pregnant, was matron of honor. Ike teased Vernon, saying they could have invited more people if Trixie hadn’t taken up so much room. Wanda Sizemore had sneaked to the side of the house and stood peering through a side window, watching as her friend made her marriage vows. It so distracted Jerry Dale’s sister Annette that to this day she has no memory of the ceremony. Only Poor Ol’ Wanda peeping through the window, straining to see her friend Jerry Dale marry the handsome Ike Gibson.

Within a year of marrying, Ike and Jerry Dale bought a house. It was modest—just two bedrooms, one bath—but it fit their needs, and they could just afford it using the G.I. Bill and money they’d saved. It sat dwarfed between the sprawling brick homes of a well-to-do ranch family on the east and a farm family on the west. Jerry Dale’s father, Red Griffin, was a general contractor. He built the house, and, although it was plain on the outside, he added some special touches to the inside. The dining room was divided from the living room by a pretty set of French doors he’d rescued from a remodeling job. There was varnished knotty-pine paneling in the living room and a half-wall of built-in bookshelves beside a small fireplace. He made the mantel by hand and inlaid a beautiful piece of wood into the center of it, a piece of mahogany he’d carried in his toolbox since Jerry Dale was a baby that had meaning known only to him. The mantel was lined with pictures alongside other precious keepsakes. Among them, in a small silver frame, was a smiling, freckle-faced, five-year-old Jerry Dale wearing a fur collar with her hair in rows of waves.

Six years passed before Ike and Jerry Dale brought a baby girl home to the house. Less than a year after that, they took in all four of Jerry Dale’s sisters. The little house might have burst at the seams to hold them all if it had not had a bottomless capacity for love.

A few years after her sister Vonda returned home from Waxahachie College, Wanda Sizemore, the big twin, left Dixon. She left without a goodbye or a forwarding address and never saw her mother or sister again.

But in a twist of fate, she did see Jerry Dale again in a most surprising place. Ike and Jerry Dale and their little girl Priscilla were at Yellowstone National Park, standing in front of Old Faithful waiting for the storied geyser to erupt. Jerry Dale was rattled because five-year-old Priscilla, an ordinarily well-behaved child, had just staged a scene in the gift shop when Jerry Dale had tried to persuade her against buying yet another book—this one about Yellowstone’s bears—and Priscilla was so determined to have it, she hid under the display table, refusing to come out until her mother agreed.

Soon after, Priscilla was standing in front of her father, holding her mother’s hand and gripping the bear book in the other hand, listening to a tall, lanky park ranger explain in detail about the geysers. The ranger was impressive-looking in her green uniform. The ranger hat pulled low on her forehead cast a shadow across her features, making it hard to see what she looked like. But her voice was so animated, her enthusiasm about the churning bubbling geysers and geothermal pools and the ancient origins of them was so genuine, it was contagious. The trio was spellbound. At one point, she began to explain the depth and temperature, and something in Jerry Dale clicked. “Well, I’ll be! Wanda Sizemore, is that you?!” Wanda turned to her old friend and said in a confident voice without a hint of the shyness and self-conscious embarrassment she had years ago, “Jerry Dale, I wondered if you would recognize me.”

Share this post